The art of movement: Arsenal great Ian Wright on playing with Dennis Bergkamp and scaring defenders

In the latest instalment of our series on football's finer crafts, one of the Premier League's greatest strikers reveals the hard graft behind learning to terrorise defenders

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A striker’s ability to escape the attention of a defender, to find space in the most fiercely guarded areas of the pitch, is often considered innate, an instinct the game’s greatest goalscorers carry within them. But this assumption fails to appreciate the dedication, the trial and error, the science required to master movement.

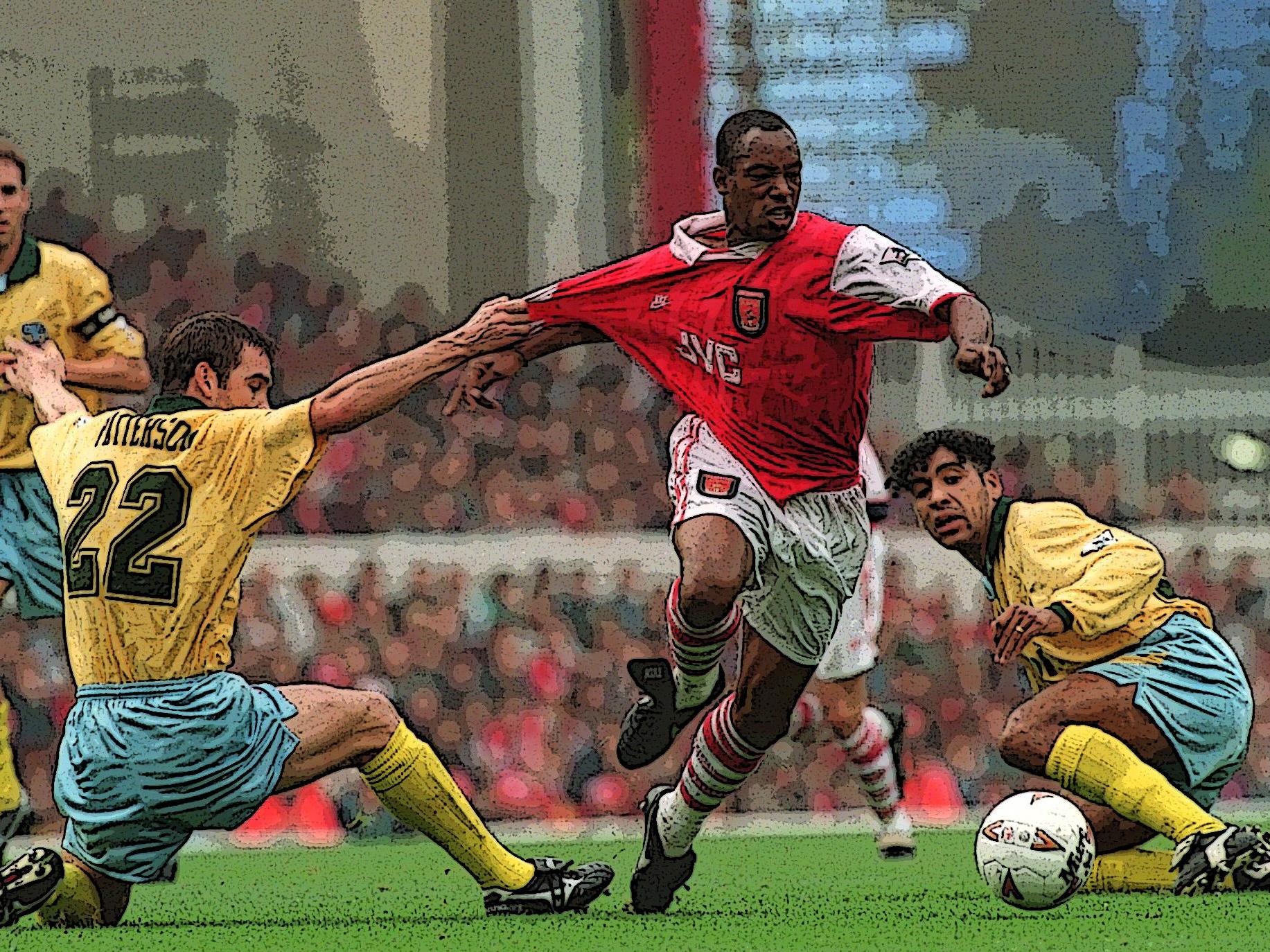

Ian Wright was one of the greatest strikers of his generation, a scorer of record-breaking regularity during a 15-year career which saw him rise from non-league football to stardom with Crystal Palace, Arsenal and England. A lethal finisher from almost any range or angle, he found simply putting the ball in the net effortless. The subtle art of decoy runs and the careful timing of bursts into the box, though, did not come as naturally.

“When I was younger and I used to watch strikers, it was never the movement I was looking at,” Wright tells The Independent. “I was looking at Cyril Regis holding it up, Laurie Cunningham doing skills, things like that. I never realised movement was important. When I played Sunday morning football, movement wasn’t something that I needed to worry about, because I was so quick. They’d just put it over the top, and I’d run over there.

“Once I got to Palace, my movement wasn’t great. I didn’t know that when the ball goes from the centre-half into midfield, you’ve got to be doing something so the defender is thinking, ‘What’s he going to do?’”

International recognition arrived late for Wright. He was 27 years old, had scored 118 goals for Crystal Palace and was just three months shy of finishing his first season with Arsenal as the First Division’s top scorer when Graham Taylor handed him a first England cap in February 1991. And the belated chance to join up with the country’s best players proved as educational for Wright as it was a moment for proud reflection.

“When I got into England,” he says, “I watched Gary Lineker. I saw him roast Des Walker once – and Des Walker was the best – by bringing him towards the ball then just spinning him. The way he did it, he was like a possum; he sucks you in like he’s not interested, running towards the midfield, then bang.

“When we went on a tour of Australasia [in June 1991], [coach] Steve Harrison took me aside and taught me how to bend my runs, how to go in behind a defender or come into feet, how you make an extra yard of space. Steve Harrison spent easily 45 minutes after training with me, every time, about my movement. It was invaluable to me.”

A striker’s ability to find or create space is a collaborative effort, working in sync with the midfielders who will slide through-balls in behind with perfect timing, wingers who deliver crosses reliably into the most dangerous areas, and strike partners who will drop deep or pull wide to link play.

“You’ve got to understand the midfield player who’s on the ball,” Wright explains, “and the capabilities he’s got in respect of finding you and how quickly he can find you. You can imagine, once I got involved with Patrick [Vieira] and Manu Petit, and Dennis [Bergkamp], my ratio went up.

“You’ve got to be involved at all times: ‘OK, Lee Dixon’s got it. I’m just going to amble over towards the left-hand side and suck this defender in.’ Then if Marc Overmars gets it, or Lee Dixon puts it over the top, I bend my run and I’ve got loads of space over on the left-hand side.

“It’s all about making sure that when the ball is moving about in midfield, all I’m thinking about is, ‘Where is [my marker]? Is he behind me? Is he on my shoulder?’”

Battling opposition defenders was a challenge Wright always relished. At 5ft 9ins, physical contests with towering centre-halves were to be avoided. Instead, he was cunning and lithe, meeting muscularity with misdirection to steal a march on his marker.

“Once you get into a situation where Dennis has made his move and broken through the midfield, and I’m running alongside the centre-half, you make the move like you’re going to go across [the centre-back] – and he has to go with you – then you go back the other way and you’ve got five yards of space instantly. I’d have already said to Dennis, ‘Put it in to my left, because I’m going to run him over to the right.’ By the time he recovers, you’re in on goal to get your shot off.

“The closer you get to the penalty area, the more twitchy a defender will get. Any movement you make, the defender is going to buy it. Then you can exploit them, exploit the little spaces.”

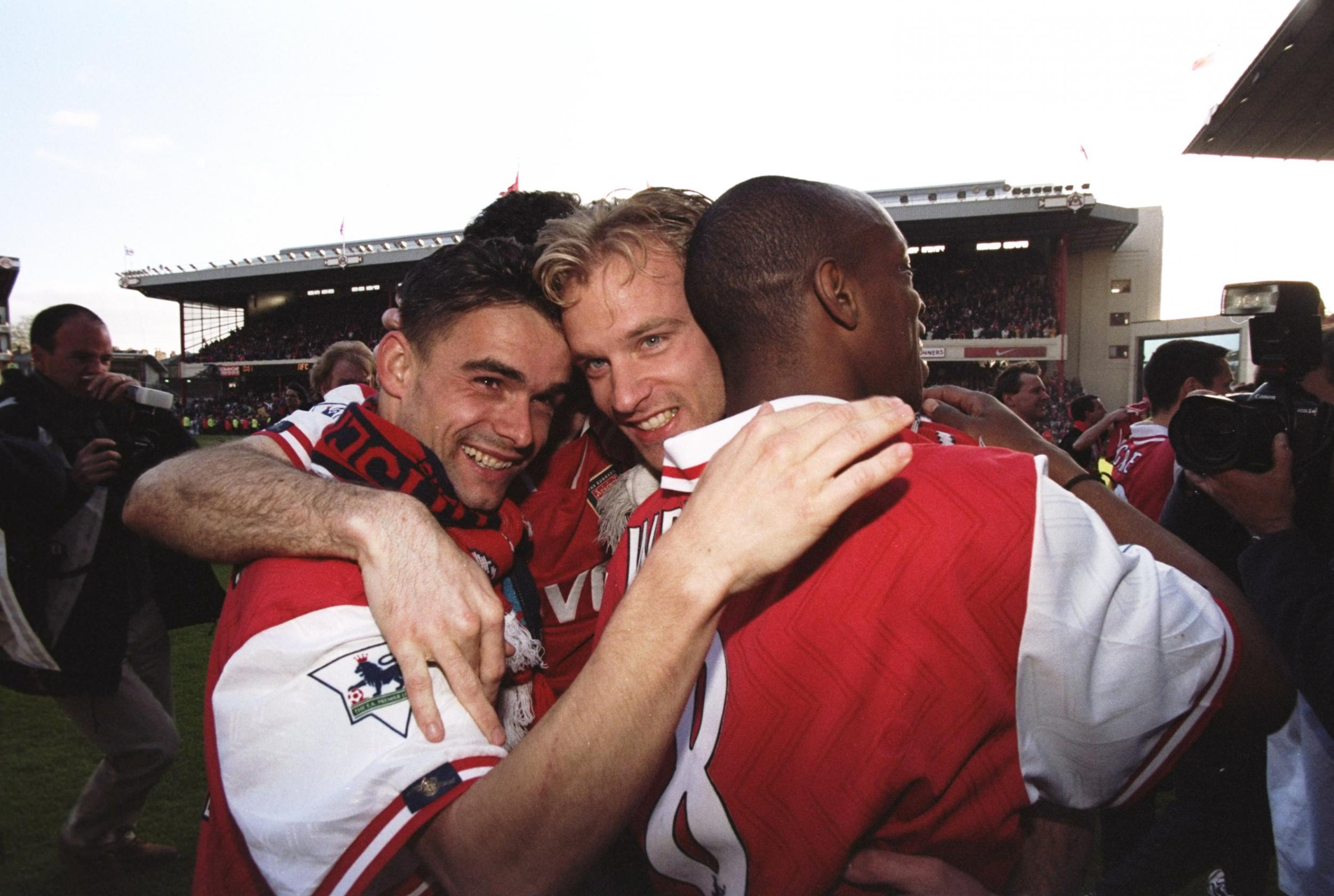

Bergkamp’s arrival at Highbury in 1995, joining from Internazionale in a club-record £7.5m deal, released Wright to be the lone out-and-out frontman, his preferred role, as the Dutchman dropped off to link midfield and attack.

“When I was up front on my own, I loved it. It was all about where I was. There’s so much space and so much confusion you can cause with defenders. They’re having to think all the time, because they’ve got one person continuously patrolling that area and no one knows who’s going to pick him up.

“It was like a chess game. Sometimes, even if the ball was nowhere near, I’d test the defender to see how frigid he is, to see if he’s scared of my movement. If I go next to him and pretend to start making a run, and he goes with me, even if the ball’s not in play, that’s when I know he’s afraid.”

While Wright is certain pace will always be one the premier assets a striker can possess, he believes there is a more to developing elite-level movement than sheer speed.

“For good movement, obviously you need a good amount of intelligence and understanding of the game – How much time has the midfielder got? How close is the defender?

“There’s a feeling you have where you know where the space is and you know where you want to end up. And you know how important it is to not cancel that space before the play has built up enough for you to exploit it.

“It’s very much possession-based now, so your movement has to be very concise in the latter stages of the pitch. It’s more about linking the play and then trying to find half a yard inside the box. That’s where someone like Sergio Aguero does it better than anyone else.”

In search of a spilt-second’s head start or an unguarded inch of space, Wright learned to initiate a battle of attrition through constant movement. He would wear the opposition backline down by making sure he occupied their thoughts at all times, pouncing on any mental lapses this instigated. Even when the other team had a corner, he’d position himself on the halfway line, walking between the two covering defenders, forcing them to pass responsibility for marking him back and forth.

“Never give them a break.” That was the Wright way.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments