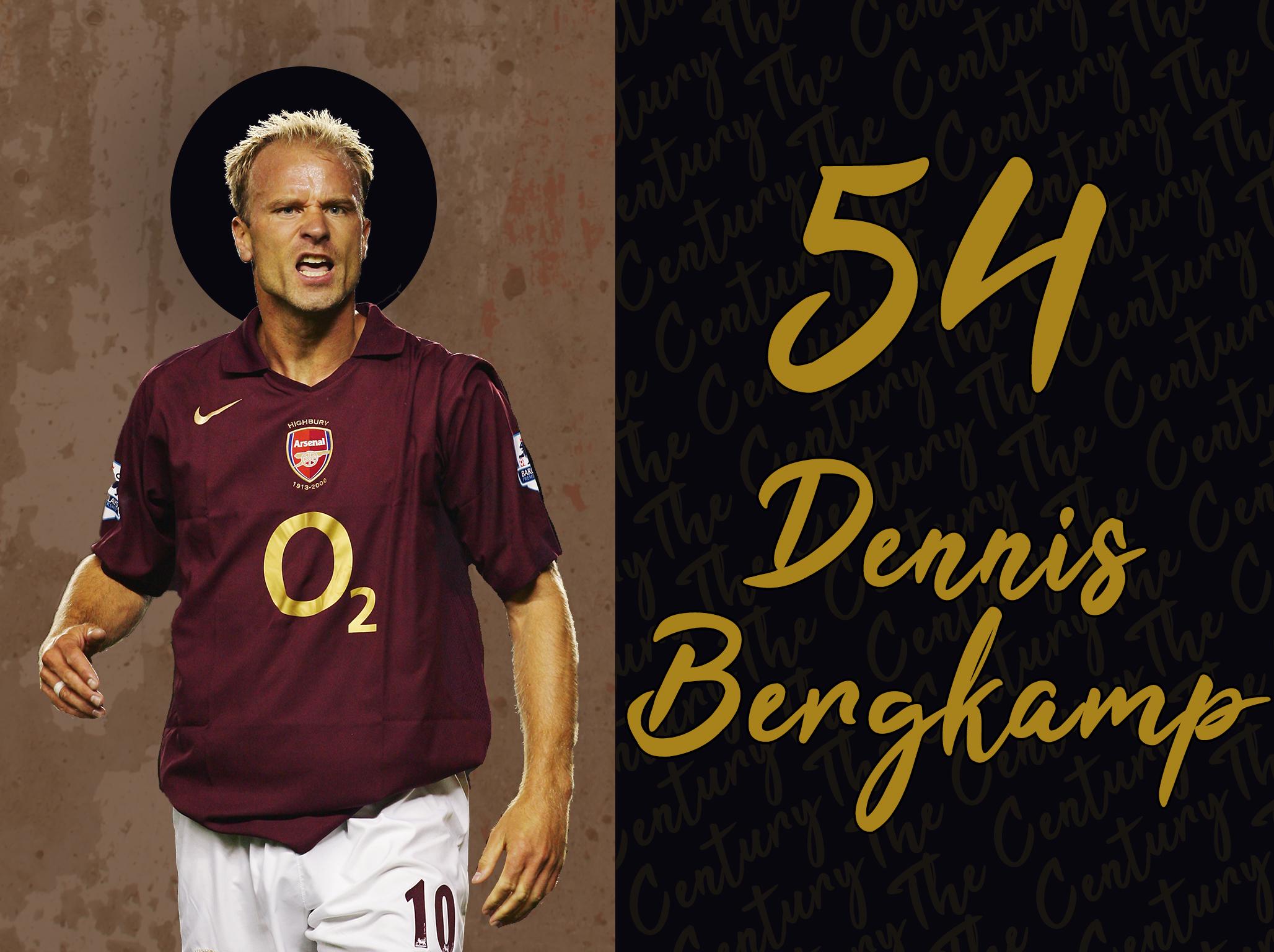

Dennis Bergkamp and the art of beautiful simplicity

The Century: This week, The Independent is counting down the 100 best players of the last twenty years. The Non-Flying Dutchman is placed at 54 on our list

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Four years after 2001: A Space Odyssey was branded hypnotically dull by film critics, Stanley Kubrick reflected on the legacy of his masterpiece. The problem, he said, was that 2001 was too original. It didn’t conform to the usual dogma we rely on to break down what the extraordinary actually is. The classical music danced where there should have been dialogue, the new-age special effects were just too disturbingly real and, yes, the sun broke over a black monolith, but where were the bloody aliens?

In football, logic has always told us that greatness can be compartmentalised by medals, scores and statistics. But, every so often, a player comes along who refuses to conform.

Dennis Bergkamp might have notched fewer goals than James Beattie and won half the number of Premier League titles as Phil Neville. He may never have broken records or incited new eras in the way Thierry Henry or Cristiano Ronaldo did during their time in England. But nobody could deny that Bergkamp produced moments of bona fide astonishment, graceful flashes that raised an invisible bar, made football freeze, froth at the mouth, and then speak about them forever.

Often the most revealing sides to players are found when they speak about one other. They tend to home in on an attribute that can easily be quantified: the speed of Kylian Mbappe, the passing of Andres Iniesta, Razor Ruddock’s ability to play a grizzled hacksaw of a defender or dote on a parboiled kale leaf on Masterchef.

At home in the shadows between Henry and Patrick Vieira, Bergkamp was never the maestro of any one distinct fundamental. Yet when players speak about him, it’s like they’re attempting to analyse something other-worldly. A depth of understanding with a ball at his feet that, even to his fellow pros, felt hard to relate to. “It was so beautiful,” a young Robin van Persie said after watching Bergkamp train. “To me, it was plainly art.”

Bergkamp’s pivotal role in Arsenal’s double-winning season in ’02 or the Invincibles two years later are the ordinary litmus tests to his genius. But it was that not quite decipherable mystique that translated into snippets of sheer individual brilliance.

Those breathtaking moments – one pin-drop swivel to bemuse two defenders and a flick to set Freddie Ljungberg free against Juventus; a weightless hook to poach Frank de Boer’s cross from the skies and score a 90th-minute winner against Argentina in the World Cup quarter-final; that single touch of invention against Newcastle so elegant and devastating it caused a type of football anarchy – are burned into every fan’s mind.

It was far from today’s in-your-face playlist showboating – “behind every kick of the ball there has to be a thought,” was his mantra – but Bergkamp’s unique ability to make the unnatural look so effortlessly pure is what separates him today still. “He played football like it was all a dream,” Peter Schmeichel once said. “You couldn’t even imagine some of the things that he was capable of doing.”

We live in a world spoiled by the riches of Lionel Messi and Cristiano Ronaldo, we’ve seen Neymar recreate flecks of Ronaldinho and Mbappe draw vestiges of Henry. All those are already, or will by the end of their careers, quite rightly be seen as greater players. But then, perhaps, the greatest testament to Bergkamp’s talent is how few players have stepped into the realm of lawless fantasy he so often occupied. In an era where every touch, skill and shot is amplified, Bergkamp reduced football to a state of beautiful simplicity - and that allure still survives long into his retirement.

Kubrick said a work of art is judged by our affection for it, not the ability to explain why it’s good. Seventeen years later and fans still vex themselves over whether Bergkamp actually meant that goal against Newcastle. The problem is that touch was too original. But where is the logic in that?

The Century

This week, we are counting down the 100 greatest players of the 21st century, revealing 20 per day until the winner is announced on Friday.

We asked 10 of our football writers to select 50 players, with each pick awarded points contributing to a final score.

Join us throughout the week for a wide selection of exclusive interviews and features, as we celebrate the best players of the last twenty years.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments