Denis Stracqualursi interview: Everton's fish-out-of-water cult hero who never stopped trying

Exclusive: The Argentine was often out of his depth in his short spell but as the suddenly indispensable Oumar Niasse’s example this season underlines, Goodison Park loves a trier

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Denis Stracqualursi tells a lovely tale about his fish-out-of-water beginnings in English football.

The Argentinian striker, who became a cult figure among Evertonians for his big-hearted efforts in the 2011/12 season, did not have a single word of English when he set off for his first overnight stay with his new team and ended up going hungry as a consequence.

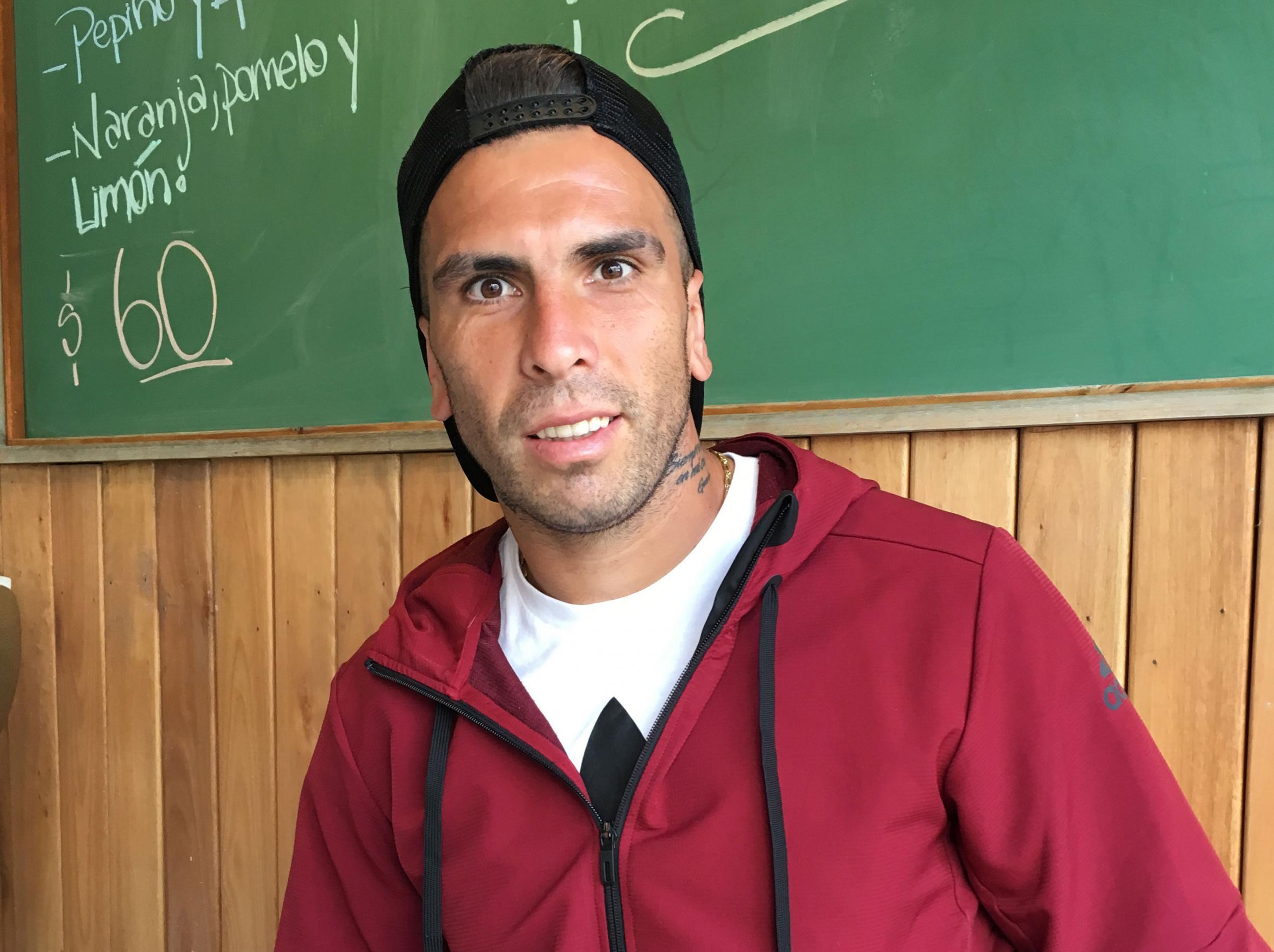

Sitting in a café in the Argentinian town of Tigre, he takes up the story. “I was used to eating at nine at night in Argentina,” he says. “The first time we slept over before a game I went downstairs at around seven o’clock, which is the time we have our merienda – some milk or a coffee with a bun. I saw the other players were eating but didn’t understand it was the custom so I got just a coffee and decided to save myself for the meal later. I then get to eight, nine, ten o’clock and there’s no food and I’m starving. I called my friend and said, ‘What time is dinner here?’. He said, ‘What do you mean, dinner? They have it at seven!’”

It is an amusing aside and illustrative of the broader sense of a young man entirely out of his depth, unable even to ask a simple question about mealtimes. Yet as the suddenly indispensable Oumar Niasse’s example this season underlines, Goodison Park loves a trier. Here was a player prepared to fly in for horizontal headers, Andy Gray-style; a player still remembered today for the rabid work rate that shook up Manchester City when an injury-hit Everton upset the champions-elect on a raw January night in 2012. “If you’ve got to put your head in, you put your head in,” he remembers. “I think the affection I got from people was because of the way I played – throwing myself to the ground and heading the ball. I wanted to win whatever it took.”

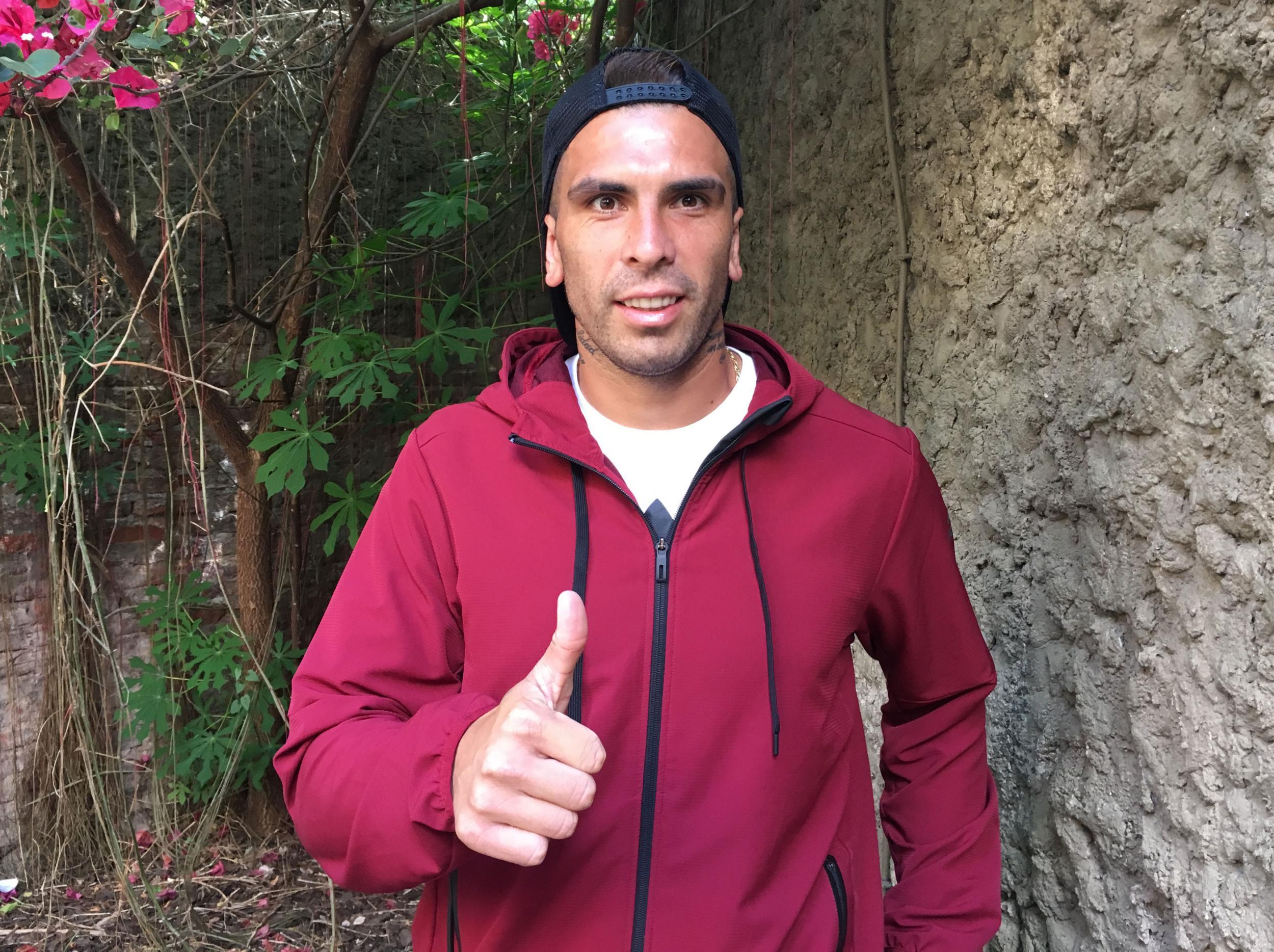

It can take the simplest of things for a footballer to connect – to ‘click’ – with a certain club and its supporters, and Stracqualursi seems genuinely happy to look back and reminisce about his own case, and the cult status he gained. We meet at the train station in Tigre, a popular day-trippers’ destination, reached by a 45-minute ride through Buenos Aires’ affluent northern suburbs.

It was with Tigre that he had made his name as the Argentinian league’s 22-goal top scorer in 2010/11, prior to his move to England. Now back at the club, he arrives fresh from training, in hooded top and shorts, before leading me to a café where he orders lunch – and begins the story of his short life as a Premier League player.

Amid the slick, swift-footed South American imports who have graced our top flight, he resembled a product from the discount shelf: a lumbering No9, brought from a modest Argentinian club. “I’d never actually been outside Argentina before,” he says, remembering his arrival, aged 23, on the last day of the summer 2011 transfer window. He had come to England for a trial at Leicester City yet ended up on Merseyside instead. “It was strange – and fast,” he says. “It wasn’t planned.”

He adds: “It wasn’t my decision to go to Everton. It was the agent who represented me at the time, who lied to me. He said the club really liked me. It wasn’t true but there was money in it for them, but in the end it was the best time of my life.”

His new manager, David Moyes, had just lost Mikel Arteta, Yakubu and Jermaine Beckford, and his lukewarm evaluation of the qualities of his deadline-day loan gamble – “I'm not sure yet, we'll find out in time” – was hardly a vote of confidence. Settling in was not easy. “I’d never trained with that intensity. [Moyes] wanted us to train as we played. I wasn’t used to that in Argentina and that was hard for me.”

His strongest memory of the Everton dressing room is of the “sense of belonging” fostered by Moyes. Dutchman Johnny Heitinga, formerly of Atletico Madrid, and Phil Neville, then taking Spanish classes, would pass on the manager’s instructions in stuttering Spanish, though it was Neville’s actions that provided the clearest message of the standards required.

“I arrived there during the international break and lots of players were away. David Moyes had given the other players four or five days off and the first day I got to the club there was nobody there. The Under-23s were training, they were out there running and in the middle was Phil Neville. A player with a career like his and they’ve given him time off and he’s out there training. I told myself, ‘if that player – from Manchester United and the national team, with everything he has done – is out there training then I have to give five times more if I want to be at a club like Everton’.

“It really struck me the hard work these players put in – players with big names, who’d been to World Cups. I didn’t know anybody when I arrived yet whenever I said to Tim Howard, ‘Can I do some finishing practice?’ he never told me no. That humility and the work ethic is not something you see everywhere.”

Stracqualursi’s story is a reminder that new players, especially youngsters from abroad, need time. He says it took a November training trip to Tenerife for him to feel integrated – “they started to trust in me” – though it was not until January that the hard work began to pay off. There were tears when he scored his first goal in an FA Cup fourth-round victory against Fulham, and then came the 1-0 victory over Man City. “The first ball I challenged for that night was against [Vincent] Kompany. I went in with all my strength and I just bounced off him. I went in with everything and couldn’t move him.

“I had a header which the defender who used to player for Everton [Joleon Lescott] cleared off the line. It was a night you dream of. It was how a night match should be – all the fans behind you, chasing for every last ball, hanging on, waiting for the clock tick down. I was man of the match and they gave me champagne.”

Another magnum came his way after he struck his only Premier League goal in the next home fixture to complete a 2-0 win over Chelsea. “All my family at home in Argentina were watching and when I scored the goal it felt like touching heaven with my hand,” he says. “It was a day that even now I can’t keep out of my mind. If you go to my parents’ house there’s a big photo of the goal on the wall there. “There aren’t many Argentinians who go to the Premier League and even fewer who go from a team in Argentina straight to England. There’s usually a stepping stone in Italy or Spain which is easier for an Argentinian. So that moment, scoring a goal in that game, was news in all of Argentina.”

It is hard to imagine too many other top-flight footballers taking delight in attending a Player of the Month lunch for fans, but for Stracqualursi, it was all part of the adventure. As for those man-of-the match champagne bottles, they are precious mementos, never opened and now “all at home”, in the trophy room of his house in the Santa Fe province of Argentina.

Stracqualursi faded from the picture at Everton after Nikica Jelavić stepped into the team, moving back home to join San Lorenzo, yet he left considerably better memories than the more celebrated talent who had arrived at Everton on the same day as him, Dutchman Royston Drenthe. “He could do magic things on the training ground. If he’d not been so mad he could have been a great player. I thought, ‘What a waste, a player with so much ability’. He had different cars – a Rolls Royce, Ferraris. I remember one time during an international break he said to me, ‘Where are you off to?’. I said, ‘I’m going to Venice with my family’. He said, ‘You’re mad, why are you going to Venice? It’s cold there, come to Dubai with me, it’s hot’.”

Since leaving England, Stracqualursi has played in Abu Dhabi, won titles in Colombia and Ecuador but is now back at Tigre on loan. It was his year under the grey skies of Merseyside, though, that will always be his year in the sun. “I’ve seen teams lose in England but they get clapped off. Here that doesn’t happen. Because of the social problems today in Argentina, people don’t have jobs and they go to the ground to let out all that anger so football is about extremes. If you win, they love you; if you lose, they don’t. If you score, they love you; if you don’t score, they don’t.”

And, in England, he found a place where sheer hard work earned him a wave of warmth. “Just knowing that people there still remember me is worth more than any money to me,” he says, sweetly.

“Goodison Park has that look of England, when you see it on television you think that is England. It’s not the Manchester City stadium, which is so modern, but it represents where football came from, that mystique, with the people so close to you. I really felt it, the public supporting you.

“The experience at Everton was the best of all the places I’ve been too. Today my son who was only one when I was there says to me, ‘Papi, when are we going to go back to the Everton stadium to watch a game?’ When he’s bigger, I’ll take him there.”

And when he does come back, he will do his utmost to get his photo taken with another Evertonian, Wayne Rooney. After all, one regret of his stay in England is he was too shy to ask the then Manchester United player for a picture on the day their paths crossed. “We went one day to the horse races and he walked past me and said hello. I had him next to me and didn’t ask him for a photo. I was always a bit embarrassed to ask. I still kick myself for not asking.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments