Try to enjoy this weekend’s Carabao Cup final – the tournament may not be around for much longer

Despite its relative lack of importance as a trophy, the competition has assumed a key place in football’s own running culture war, argues Miguel Delaney

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

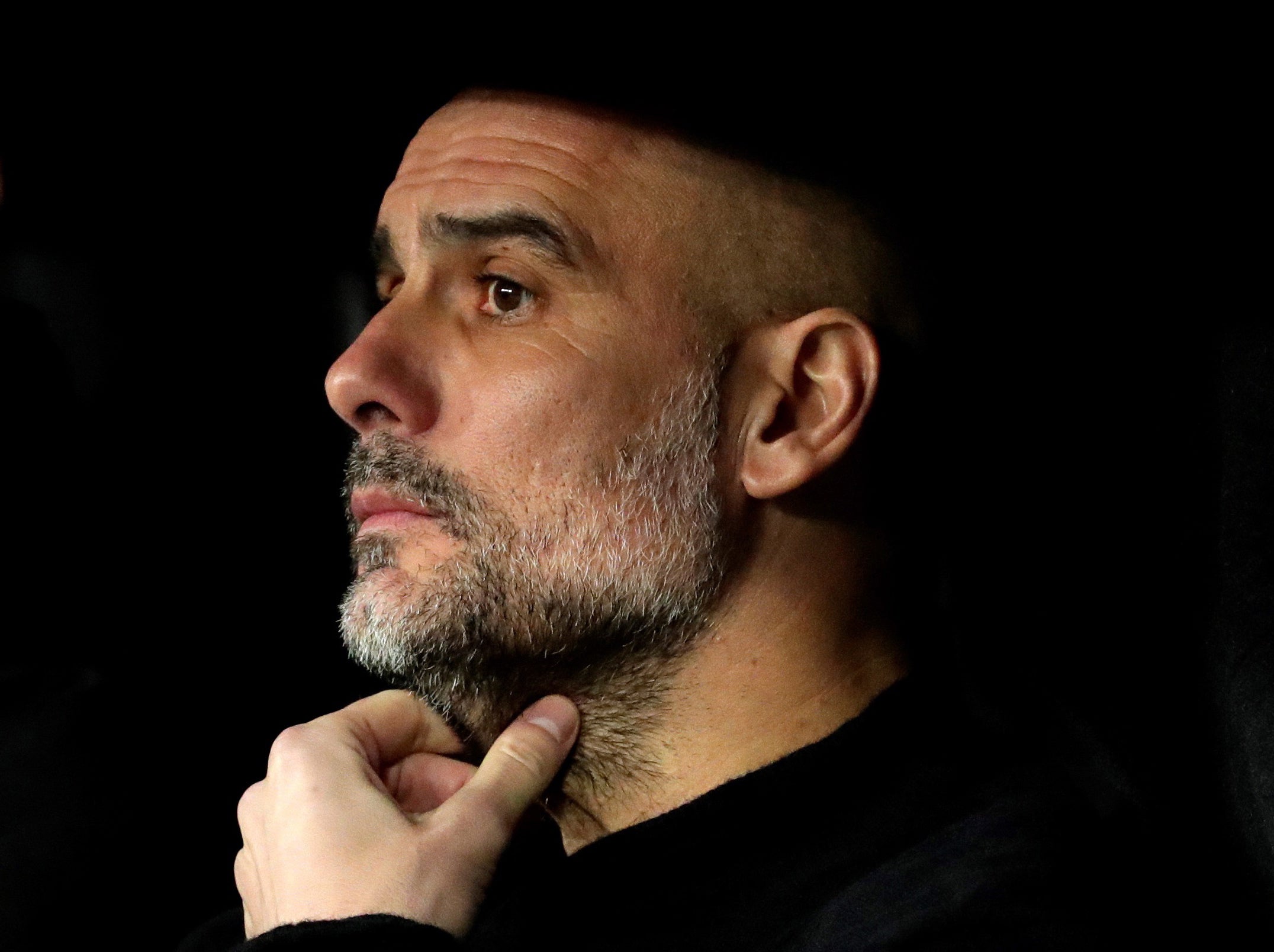

Your support makes all the difference.It seems as though he is always there, but Pep Guardiola gives the impression he’d rather be anywhere else but the League Cup final on Sunday.

The Manchester City manager, preparing for a record third successive appearance in the fixture, has pretty much said the competition shouldn’t exist.

Many within the club hierarchy, as well as the rest of the Big Six, feel the same.

That reflects another irony of the modern League Cup. Despite its relative lack of importance as a trophy, the competition has assumed a key place in football’s own running culture war: what actually matters; what should be cancelled.

That culture war has arisen from the wider financial split in the game, recently covered by The Independent, that is testing the very structure of the sport. It is currently the subject of heated discussion, as football’s authorities attempt to work out the post-2024 calendar. That is set to be done by June, but there is an awful lot of push and pull, and even more tension.

Ultimately, the wealthiest clubs at this point only want to play in the most glamorous and lucrative fixtures, against the other wealthy clubs. They don’t see why they should waste valuable time and energy on games that don’t mean that much, and don’t bring in that much.

FA Cup replays are first in the firing line in England, but the League Cup isn’t far behind. It doesn’t bring in anything like the FA Cup, for one. The winners on Sunday between Aston Villa and City will get a mere £100,000, the runners-up £50,000, paid for by the Football League.

You don’t even need the usually inevitable next sentence about what such figures are worth in relation to the players’ wages. It now feels even more inevitable that the top clubs will eventually ask – once and for all – what the exact point of the League Cup is. That’s all the more pronounced when so few other countries actually have a secondary knock-out, and France have just got rid of theirs.

It’s also a fair general question.

The League Cup was initially introduced in 1960 as competition for the burgeoning popularity of European football, and little more than that. There’s only been one winner there.

Winning, however, is part of the greater point with the League Cup now.

Silverware has always been about more than just, well, the silver.

Sir Alex Ferguson described it as a “pot worth winning”. Jose Mourinho has always seen the intrinsic value of something tangible like a trophy to foster a winning mentality. By now, too, you’ll be well aware of Brian Clough’s quotes – that are usually always referenced before this fixture – about the “taste of champagne” and what the modest old Anglo-Scottish Cup meant.

No one needs to be told what it would mean to a great old club like Aston Villa, either.

Their last trophy was the 1996 League Cup, and victory on Sunday would feel like a first moment of glory for so many at Villa Park.

Recent winners like Swansea City and neighbours Birmingham City can attest to that. Many financially poorer clubs will also talk of the value of big nights in the competition, especially for televised games. The League Cup has actually developed a distinctive new life of its own in that regard, and a new sense of basic fun. Its midweek scheduling, in contrast to much of the FA Cup, makes it feel like bonus fast-food football that is just there to be enjoyed.

The remote chances of an upset on Sunday, however, reflect another irony of the League Cup.

Despite how low it is as a priority for the top clubs, it has become a signifier of high performance; another number that bolsters the records and sums up the dominance of the great teams. Great teams have picked it up because they can.

Clough’s European Cup-winning Nottingham Forest lifted it twice. Liverpool were the first to win it three times in a row in the early 1980s, forming part of an eventual treble that included the European Cup in 1984.

Mourinho claimed it twice in three years with his first Chelsea. Ferguson then followed that by winning it three times in five years between 2005 and 2010, having initially been the first to dilute its importance by playing the kids in the mid-90s.

If City win it on Sunday, then, it will mean Guardiola’s side have claimed six of the last seven available domestic trophies. It’s eight in nine if you include the Community Shield. That is remarkable domestic dominance, best highlighted by the League Cup.

Some of this, of course, is just another indication of that financial disparity.

The top clubs can put out weaker sides and still win the competition with relative ease. No one outside the big six has lifted it since 2013, with City winning it four times in that spell.

It thereby doesn’t feel all that special to them anymore.

That is just another irony, however, given City’s Champions League ban and all of the debate about how their support feel about Europe’s elite competition. Some of their fans would have you believe they’d rather play in the Carabao Cup. The attitude of the players and staff, in contrast to Madrid on Wednesday, would tell a different story.

There’d be none of this with Villa. It would be everything to everyone there.

And this is the thing with the competition as a whole.

By supposedly meaning so little, it has come to represent a lot.

Maybe Guardiola should enjoy the stage on Sunday as much, say, as Jack Grealish and everyone at Villa will. It may not exist for much longer.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments