Brendan Rodgers may end up the Liverpool fall guy but he has not acted alone - Michael Calvin

THE LAST WORD

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Malachy Rodgers was a hero to Brendan, the eldest of his five sons. He lived frugally and for his family. Though a painter and decorator by trade, he worked for 20 years as a maintenance man for a wealthy neighbour in the village of Carnlough in County Antrim.

Money was so tight, Brendan noticed his father instinctively switched off the engine so he could save petrol by coasting downhill when he drove him to football training in Belfast. He has never forgotten the look of quiet terror in his father’s eyes when his employer went on holiday without paying him.

“My father was dependent on being paid on a Friday by this guy who had a load of money, but who didn’t probably give a shit about him,” he recalls. “My poor dad was reliant on that cash to take me to football, to feed his family. That shaped me. I would never wait and rely on anyone else.”

Such self-reliance is essential in football management, and has never been more personally relevant. A Liverpool defeat in today’s Merseyside derby will leave Rodgers friendless; he will be fortunate to survive the subsequent international break.

The tenor of the inquest is already set. Somewhere on his journey, from coaching Reading’s under-10s to managing the most emotionally driven club in domestic football, the boy has been buried beneath the brand he felt obliged to create.

The enduring respect of his peers, who recognise him as an aspirational figure and an innovative tutor, offers little protection against the public’s reflexive ridicule of his sub-Shanklyesque whimsy and earnest, occasionally gauche, self-promotion.

His values are sound, and too easily overlooked. When we met for one of his last major on-the-record interviews before he began to limit media access, I sensed the contradictions of a man of depth whose time at Anfield will be defined by superficialities.

It was as if he was drawn too deeply into the emotional complexity of his job, in moulding naturally cynical, immoderately rich footballers while marrying his principles to the astringent culture which underpins the business strategy of his American employers.

Dressing rooms can be cold places, barred to dreamers when results turn. Players have a feral appreciation of weakness, and florid philosophies expressed on flip-charts in a manager’s office have a distinctly short shelf life when it is every man for himself.

Rodgers’ profile of his ideal player is instructive: “First and foremost he needs to have talent, the personality to play at a club with this pressure. He must have the capacity to learn. Mentally, he has got to be hungry. It’s to do with desire and ambition, no matter how much you earn. To meet the demands we set, the speed at which we ask players to play, you need to be technically strong.”

Scan Liverpool’s squad list. The club’s nebulous transfer committee has not done its job. No one discusses the employment prospects of its pivotal members, head of recruitment Dave Fallows, director of technical performance Michael Edwards and chief scout Barry Hunter. Perhaps they should do so, since £200m has largely been squandered.

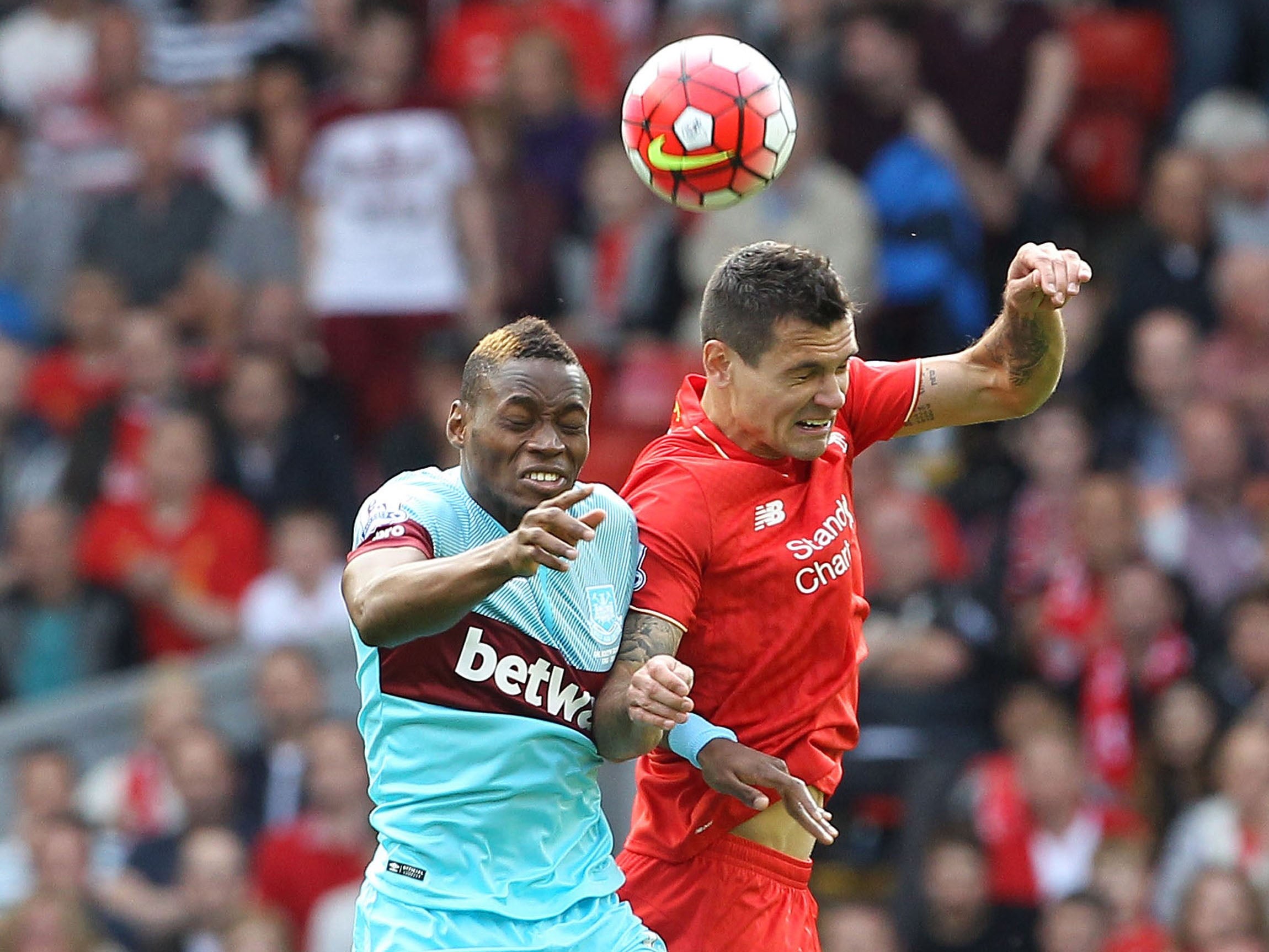

Rodgers, bound by collective responsibility and a deeply-ingrained British belief in managerial authority, is culpable for sanctioning a move away from traditional scouting methods, which raised internally-expressed doubts about the quality of such recruits as Dejan Lovren, Adam Lallana and Lazar Markovic.

It is probable that a distillation of Rodgers’ life work, a 180 page document entitled, One Vision, One Club, will soon require revision, whatever the result of today’s tribal scuffle at Goodison Park. A tipping point looks to have been reached, but it would be foolish to write him off.

He studied languages because they extend his boundaries. It would be no surprise to see him fulfil a long term ambition to work in La Liga. International football would suit someone of his nature and experience; succeeding Roy Hodgson, another anguished Anfield alumnus, as England manager would have appropriate symmetry.

Malachy Rodgers did his job well. His eldest son is a credit to him, despite the vagaries of fate.

Carneiro must be heard

The irony is overwhelming. Chelsea, a club accused of treating a senior female employee with contempt, will win the Women’s Super League for the first time if they defeat Sunderland today.

A suitably dramatic conclusion to the season will also tempt the FA into congratulating themselves for successfully expanding the women’s game, following England’s success in the World Cup.

That would be unbecoming, since their credibility, and Chelsea’s status as responsible corporate citizens, has been shattered by the injustice endured by Eva Carneiro.

Jose Mourinho’s insulting, infantile behaviour towards a highly respected doctor should neither be forgiven nor forgotten, since it compromises his professional reputation.

As for the FA, their disarray, at the start of what they are promoting as Girls Football Week, is not difficult to discern.

Greg Dyke, their chairman, chose to score cheap points in a leaked rebuke to Chelsea’s manager. Heather Rabbatts, an independent FA board member, was infinitely more authoritative in her criticisms.

A supposedly independent disciplinary process is consistently flawed. Administrative incompetence in the women’s game is highlighted by the case of Manchester City’s Keira Walsh, falsely accused of being an ineligible player because the FA lost her registration form.

The one person to emerge with credit and dignity has been Carneiro herself. She sees beyond personal circumstance, to the damage done to the cause of women working in the game by the impression that sexist attitudes and abuse are not taken sufficiently seriously.

Her voice must be heard, and amplified by apologies from those who should know better.

Georgia deserve more

The wonderment of Mamuka Gorgodze, the Georgia forward, as he realised he had been named man of the match in Friday night’s loss to the All Blacks will be an enduring image of this World Cup. He, and an emerging rugby nation, deserve broader recognition, in the form of inclusion in a meritocratic Six Nations Championship featuring promotion and relegation.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments