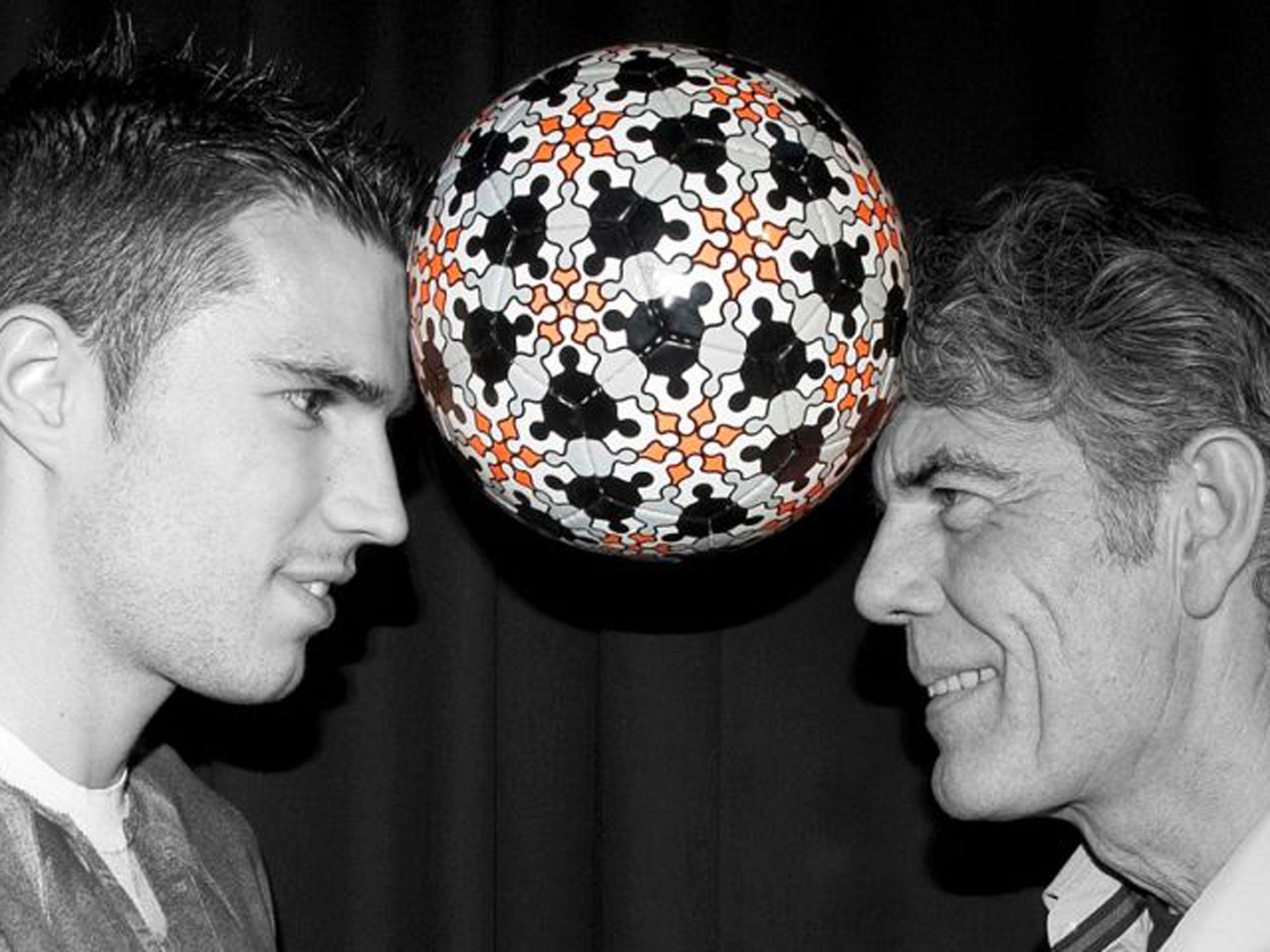

Bob van Persie interview: Meet the other artist in the family

Bob and Robin van Persie are masters of a different kind. But the Dutch striker’s father tells Ian Herbert how they are blessed with similar creative instincts

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The creative output from a certain Van Persie family began long before its most famous member listened to “the little boy inside me” and took his football talent to Old Trafford. Bob van Persie, artist and sculptor, was a part of daily life for a million people who saw his installations in a pedestrian tunnel at Rotterdam Centraal railway station and then developed the distinctive style for which he is now known – distinctive models of crowds, formed in paper by the creation of tiny, individually shaped heads and shoulders. “The paper artist,” they call him in Holland.

The slightly delicate part of our interview, ahead of an exhibition of his work which opened in Manchester this week, is how far to take the talk about Robin before he begins to crowd out the art. And that moment certainly does arrive.

“Are you come only to write about football?” the artist asks, when we’ve meandered through the formative years of the player who consumes so much conversation in this city. “Robin in my life has got two sides,” he reflects, after a diversion back to his art. “It’s a blessing and it’s a curse. The blessing is it brings a lot of publicity for me too. The curse is that it’s hard to keep your own identity. Yes, I have an identity. But his is bigger….”

His son is blessed with the intelligence to discern this difficulty. It is why he was not at the launch of his father’s exhibition at the Richard Goodall Gallery in Manchester’s Northern Quarter on Thursday. “It will be all about me,” the player said. And it should not be, because you can lose yourself in van Persie’s mesmerising crowds of ‘people’ – the heads he models are faceless and yet somehow alive. He carefully selects the paper he makes them with: a Hong Kong telephone directory for Hong Kong People and the Arsenal FC magazine for a football crowd at the Emirates. The Arsenal paper was less pliable and not so easy to work with, he’ll tell you.

Football has been fundamental to both men, though, because the father is gaining his artistic inspiration at the precise moment his son is undergoing his final preparations to play. He will get to a match maybe an hour or more early, “and the stands on the other side are all empty,” he says. “You see them fill up and then you see a picture being born, every day another one. It fascinates me. Sometimes if the game is boring I just watch the crowd.” Only the installation artist Spencer Tunick has shared quite such fascination with large groups of people and the result is highly original. Van Persie’s distinctive Sparkling Moment crowd, infiltrated with eight bulbs which blink intermittently, captures the crowd near the corner flag “who always start flashing their camera because they know the camera is on them.”

It’s been like these with him and crowds ever since those years spent watching his son work his way through the Dutch ranks – a road which began on the day he turned up with the five-year-old Robin at SBV Excelsior and suggested that coach Aad Putters might want to bend the rules stating children had to be six or older to join. “You must realise that when Robin was young I always went with him and you see small stadiums and they get bigger and bigger,” he says. “As the player grows, the stadiums grow.”

Robin’s chosen path might seem improbable, given that both his sisters, Kiki and Lily, are artists like their father. “The only one in our family who was into football was Robin’s grandfather – Robin’s mother’s father (Wim Ras),” he says. “He was a goalkeeper all his life. Not for a big club but certainly in the Dutch leagues.”

There is a creative inheritance, you might say. The older man believes most strongly that “there is art in football” and his son has always thought so too, even though he doesn’t see things the way his artistic parents do. “They can look at a tree and see something amazing, whereas I just see a tree,” Robin said a few years back. “But I think there is a creative connection with my parents.” (He was a child when his mother Josée Ras, a painter and jewellery designer, was separated from his father, who brought him up.)

You also feel there might be a shared brooding on failure between father and son. The artist describes the occasional struggle to realise his vision in an interview for the book which accompanies his exhibition. “Realisation is a stubborn process,” he says. “Failure lurks. You become introverted, like breeding hens that should not be disturbed. And then the shell cracks.” The same must be said of his son on a football field – Anfield two weeks ago being a case in point – when the ball is not rolling smoothly.

But the inherited gene which his father most sees in his son is the work ethic. “We both work very hard to achieve what we want, you know,” he says. “And I think that’s important too. It doesn’t come by itself. He has had to work hard.” Football people will also always tell you that the way a child is parented counts for as much as the genetic inheritance. “If a boy’s brought up properly, you only have to teach him about football,” Sir Matt Busby always used to say, and those who have tracked the course of the Dutch footballer’s career will tell you all about his father. It wasn’t always straightforward.

Robin was a challenging boy before football provided a focus for the hyperactivity and the paternal benevolence worked. When Robin was a 19-year-old, living with his father in the old Rotterdam neighbourhood of Jaffa, the artist’s collages of Feyenoord – the teenager’s club at the time – lined the walls. He has chronicled his son’s career in binders, too: scores upon scores of clipped, mounted articles, which you’ll find at his studio – a converted riverside waterworks.

Only now, aged 66, does he seem to be discovering some of his son’s vaulting ambition. This is his first exhibition outside of Holland – and yet van Persie’s work reveals a deeply creative and inventive mind. The 40 works now on display capture the masses arriving at Mecca for the Haj, for example. There are skylines of New York, London and Rotterdam laden with people. Wimbledon conveys the crowd watching the ball in flight. A tiny image of Robin’s face appears at the centre of an untitled piece – the exhibition’s ‘Where’s Wally’ moment – which happened by sheer a fluke of wrapping, the artist insists. Humour permeates the work.

There is a colloquial Dutch word – eindsprint – ‘the last push for the finishing line’ – which he says describes his mindset now. “I don’t have eternal life,” he says. “It’s now or never. I want to do a lot more and time is running out. As you get older the days get shorter, time gets shorter….” On the basis of genetic inheritance, we can safely assume that his 30-year-old son may also feel that sense of finite time and opportunity. A season of 26 Premier League goals for Manchester United will not be enough for him. Expect more creative output to come.

The artist has always felt that there was a little bit of destiny about his son’s life taking the course it has – and that exhibition book interview explains his convictions about some form of pre-ordination. “One’s natural tendency is converted into action,” he says. “A footballer becomes a footballer, a baker a baker, a musician a musician and an artist an artist.”

There was also a significant encounter with a clairvoyant, when Robin was two weeks old. “She said he is the only one in your family where money flows like a river,” he recalls. “She told me: ‘He is going to be a king on the sports field and on the Dutch national team’. I always believed that. When he could hardly stand he was always with a ball; all kinds of balls. In the house, I gave him balloons, so everything went in slow motion. A tennis ball, football, plastic ball, beach ball, anything. You know, he is very good at any ball sports – billiards, table tennis – he is always the one with the ball.

“I remember one day when he was a child we had this eclipse and I took him out of his bed late at night and said, ‘Come on, I’ve got to show you something.’ So we went outside to the first and stood on the bridge and you could see the shadow of the earth slowly move over the moon. And I told him that was our shadow, that we were standing on. And then he realised that we were standing on a huge ball. That fascinated him. Even the world was a ball.”

‘Bob van Persie – One Man, Full House’ is open free to the public until October 5 at Manchester’s Richard Goodall Gallery. The pictured ‘Persiball’, is being exhibited at the National Football Museum

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments