Walter Tull spent his whole life breaking down walls - it's time he was properly acknowledged and we learn from his tale

Tull, the British Army's first ever black infantry officer, as well as one of the country's very first black footballers, died during World War One - the lessons that his story can teach us are legion

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

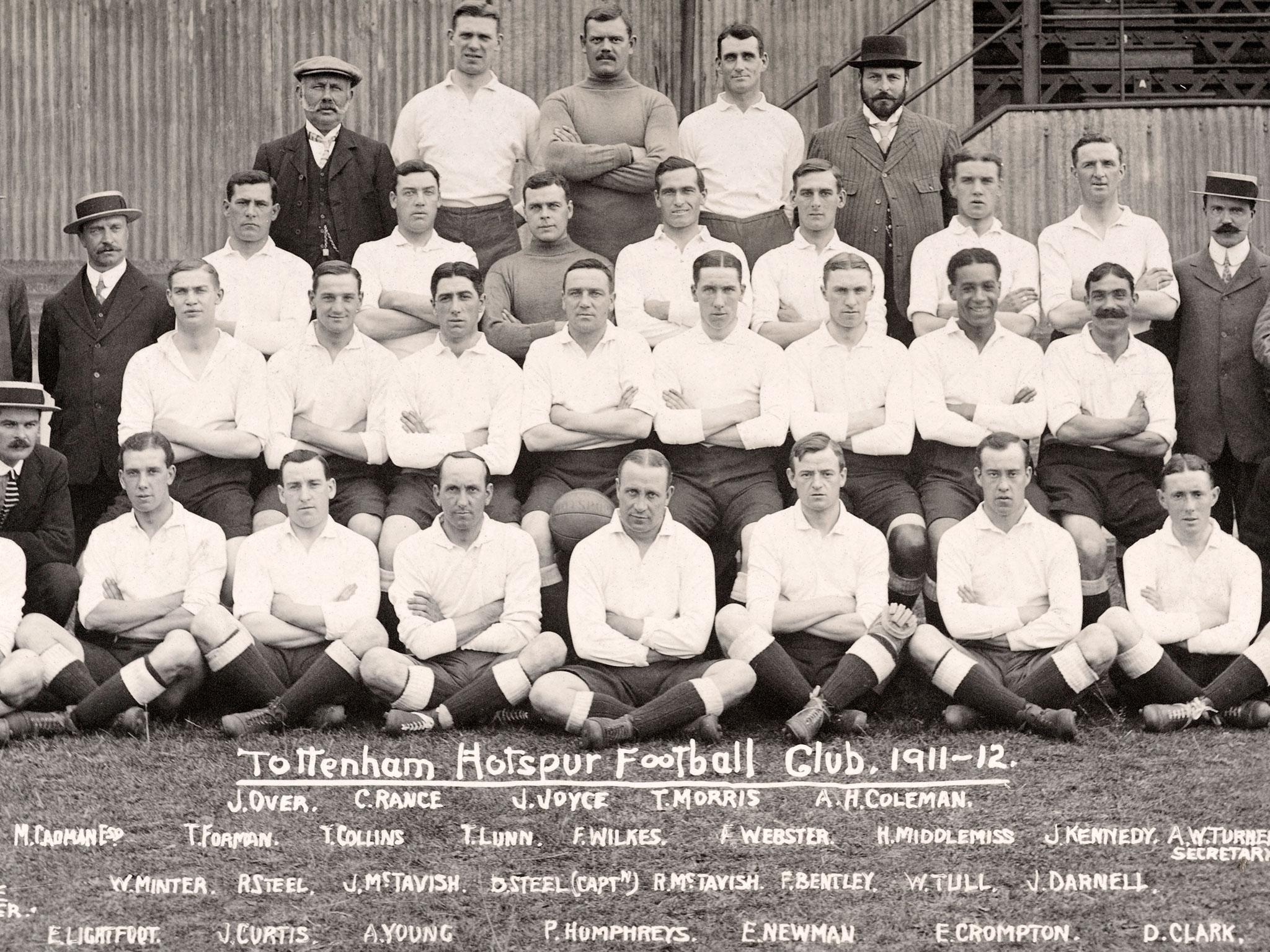

Your support makes all the difference.Walter Tull died 100 years ago on Sunday. Don’t worry, I hadn’t heard of him either until this week. His football career in the early part of the 20th century - first at Tottenham and then at Northampton - was largely undistinguished. In total, he spent just five years in the professional game. And if that were all there was to the Walter Tull story, its place in the footnotes of footballing history would be largely unchallenged.

But of course Tull was no ordinary footballer, and to revisit his tale a century after he lost his life in the festering mud of the Western Front on 25 March 1918 is to be reminded of the old saw that is as true today as it was a century ago: that those who fail to learn from the mistakes of the past are doomed to repeat them.

Tull was an inside-forward: diminutive, but sharp and quick and fiercely clever. Yet if contemporary descriptions were anything to go by, it was not always his ability that stood out. To the Daily Chronicle, he was “the coloured centre-forward”. To the Football Star, “our dusky friend with his clever footwork”. To the Weekly Herald - and this may well be my favourite - “the Clapton player whose complexion shows that he hails from sunnier climes than our own”.

Yes: Tull was black. He was, in fact, one of the very first black footballers to play in the First Division, born in Folkestone in 1888, the son of a carpenter from Barbados, the grandson of a slave, orphaned at the age of 10. After catching the eye playing for non-league Clapton, he was signed by newly-promoted Tottenham on a £4 weekly wage for their inaugural season in the top-flight, and began the season with one goal in seven league games, which while hardly incendiary is at least better than Vincent Janssen managed.

In an ill-tempered game at Ashton Gate in October 1909, however, Tull was mercilessly barracked and racially abused by Bristol City fans. For reasons that remain unclear, Tull barely featured again for Tottenham after that, and was sold to Herbert Chapman’s Northampton at the end of the following season. There he remained until 1914. At which point, war broke out.

What little we know about Tull’s life, footballing career and military service has been painstakingly pieced together by the historian Phil Vasili. According to Vasili’s book, Tull enlisted in the 17th Batallion of the Middlesex Regiment. He fought at the Battle of the Somme, at Messines and Passchendaele. His bravery, leadership skills and calmness under pressure saw him swiftly rise through the ranks: lance corporal, lance sergeant, sergeant. Then in May 1917, with the Army desperate for new officers to replace those being slaughtered on the Western Front and defying its own regulation demanding that officers be of “pure European descent”, Tull was appointed second lieutenant: the first ever black infantry officer to serve in the British Army.

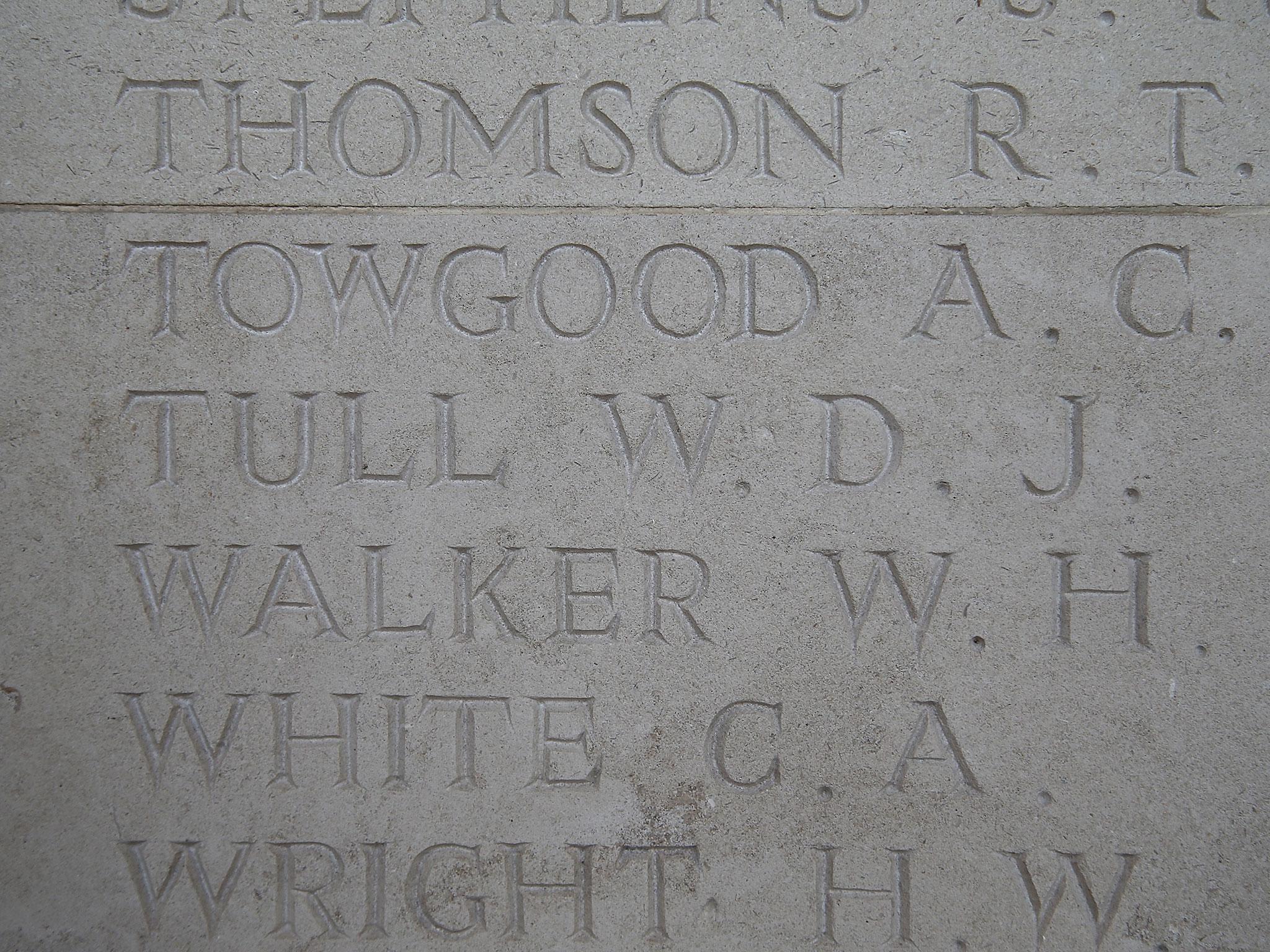

In March 1918, a month short of his 30th birthday, eight months short of the Armistice, Tull was killed while his batallion were resisting a fierce German assault in northern France. Nobody quite knows how, or where, or even in what country: his place of death was officially recorded as “France or Belgium”. Such was the esteem in which he was held by his troops that they risked their lives trying to find his body, without success. In a letter, one of his colleagues wrote that at the time of his death, Tull had been recommended for the Military Cross.

For most of his life, and indeed most of his death, Tull was a largely anonymous figure. Slowly, that is beginning to change. The Royal Mint issued a commemorative £5 coin in 2014. The centenary of Tull’s death will be marked by a memorial service in Northampton, the same town where a statue of Tull was unveiled last year. Officials from Tottenham Hotspur will also be present, and the club will also commemorate Tull on its social media channels. Next week Ledley King will attend the launch of a new education workshop based on Tull’s life and career.

And today, 127 MPs, from six different parties, have signed a letter to the Prime Minister requesting that Tull finally be awarded his Military Cross. You see, he never got it. As a black man, he should never have been made an officer in the first place, which by the curiously perverse logic of the British wartime establishment meant he should never have been eligible for one. As recently as last August, the Ministry of Defence refused again on the grounds that decorating Tull posthumously would set a precedent.

Which, of course, it would: a glorious, long-overdue precedent. Tull spent his whole life breaking down walls, whether it was at White Hart Lane or on the Western Front. “We need and want him to be championed in our schools, and among our young people, for his bravery, for his pioneering position as a black footballer, at a time when racism and prejudice was pervasive in our society,” says David Lammy, the MP for Tottenham who penned the letter. “We should right the wrong, and celebrate a true British hero.

“Walter Tull was adopted. He played football at a time when fans were not receptive to a black footballer. He led men over the top in the First World War, and was recognised by the men he saved. But he wasn’t treated very well by the system. There’s so elements of his story that can inspire a generation. British society has moved on hugely, but prejudice and racism are still with us. And football has the alchemy to reach places that other aspects of life can’t.”

Of course, it’s important that people know about Walter Tull. But there’s a difference between recognising our past, and reckoning with it. Because it is only through the latter that we can learn from it, and the lessons that Tull’s story can teach us are legion. The gnawing persistence of prejudice. The stupidity of war. And the quiet gallantry of the hundreds and thousands of women and people of colour who stood against the overwhelming tide of history and just did their thing.

Let’s at least try and understand how we got here. And let’s not stop.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments