Ron Yeats – a Liverpool colossus, FA Cup winner and a shadow of his former self

An extract from a new book, Liverpool Captains, delves further into the relationship between playing football in the 1960s and Alzheimer's disease

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

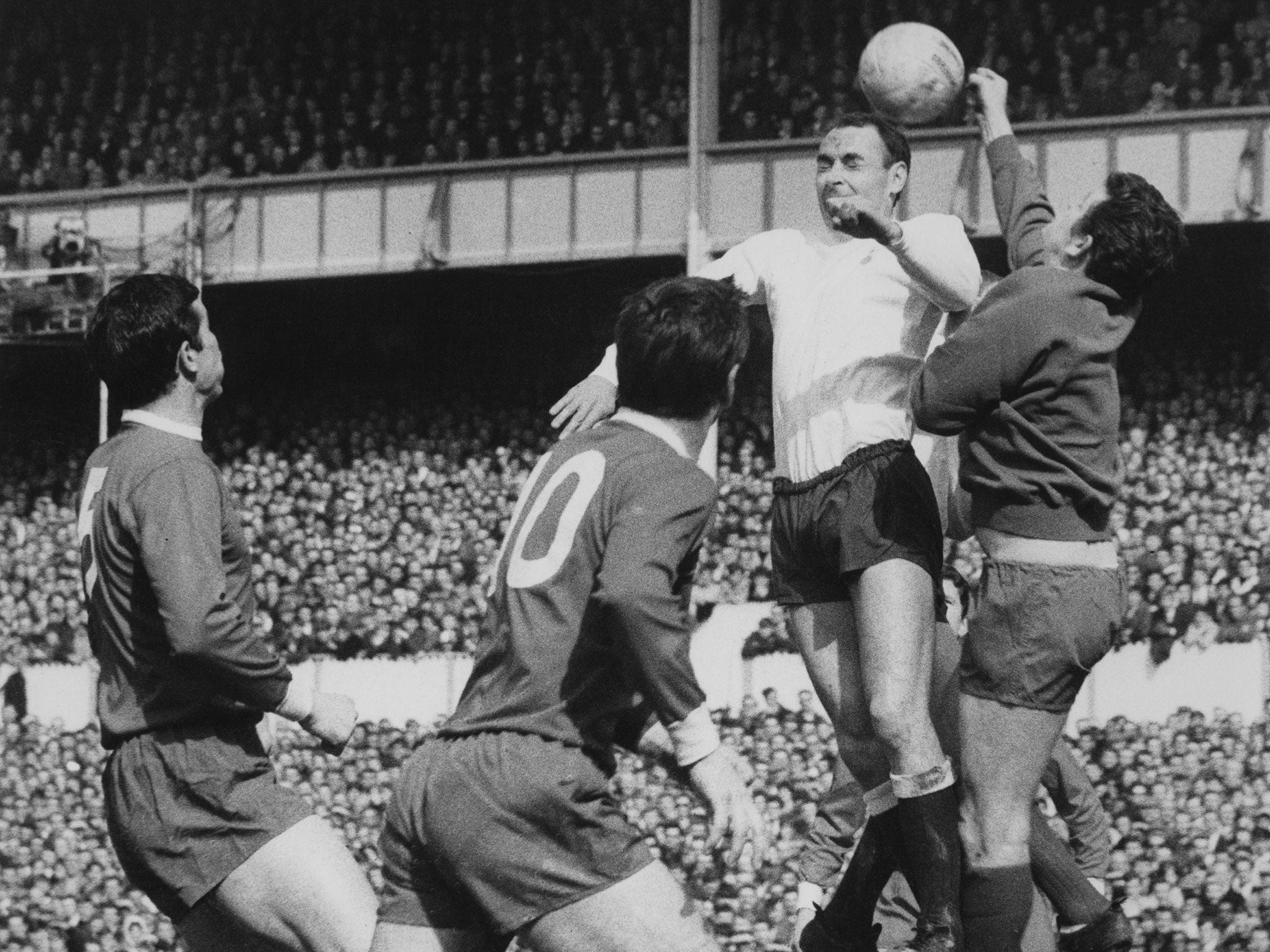

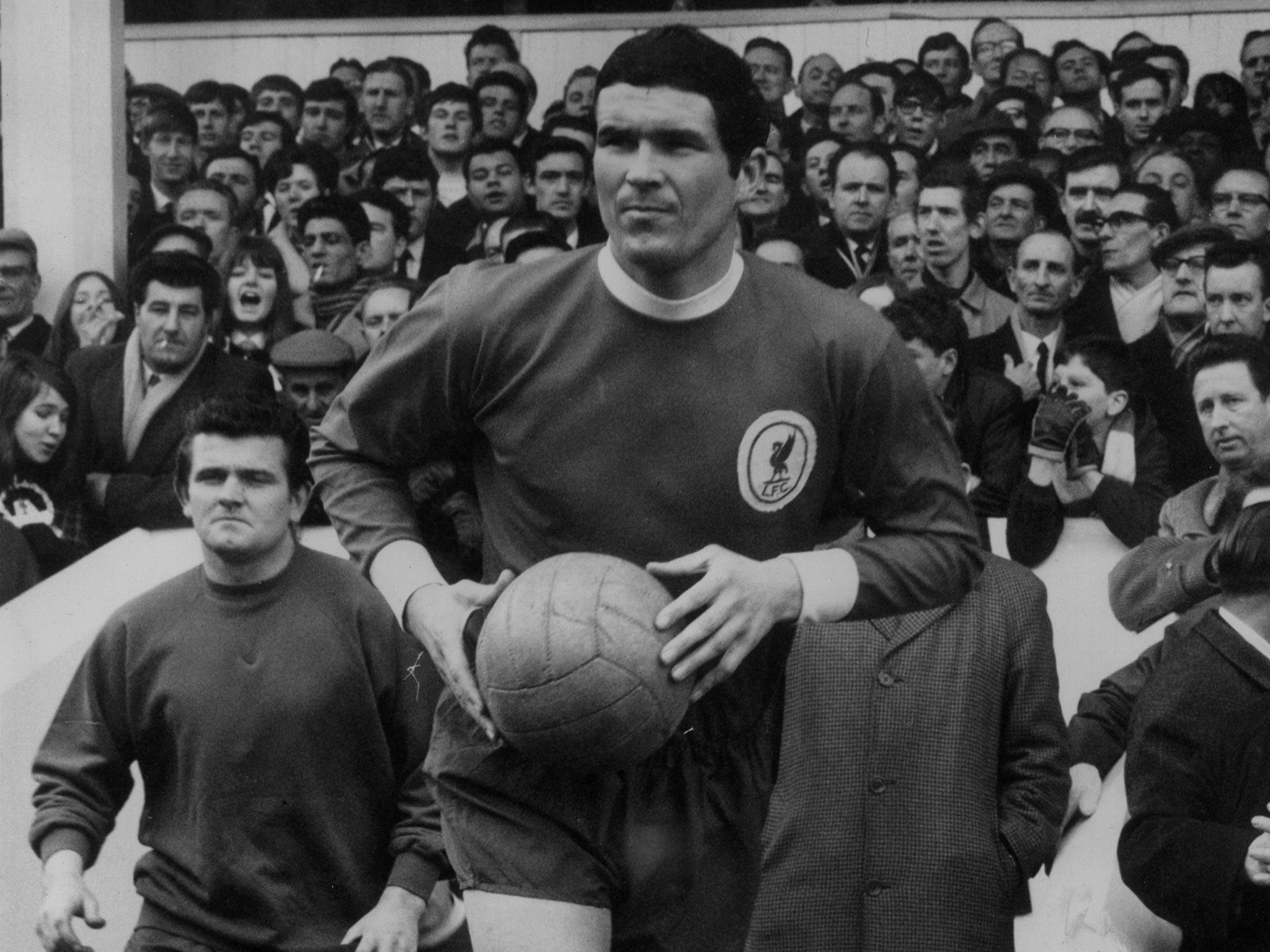

Your support makes all the difference.‘Take a walk around my centre-half, gentlemen, he’s a colossus!’ Bill Shankly grinned happily at the press conference announcing Ron Yeats’ arrival at Liverpool in 1961, imploring reporters to ‘go into the dressing room and walk round him!’ ‘The Colossus,’ Shankly called him. Yeats would also go on to be the longest serving captain in the history of the club (a record Steven Gerrard later surpassed). He was a mile ahead of the man in third place: Emlyn Hughes.

But these days it can be difficult for Ron Yeats to find the right words. All those years of heading the super-heavy leather ball out of defence, or scoring headers from a set piece, has weakened his memory. He suffers from Alzheimer’s disease, like so many other players from those days, and over the last year some memories have disappeared. So his friend, Ian St John, takes me to visit the man who set the standard for leadership on the pitch for Liverpool.

The first time Yeats spoke with Shankly, he asked if Yeats knew where Liverpool was. Yeats thought it was a geographic question, but he was wrong.

‘We’re in the First Division of the English league,’ Shankly said, answering his own question.

‘Oh, I thought you were in the Second Division, Mr Shankly?’

‘Yeah, but we’ll play in the First Division after we sign you, son!’

His memory may be fading, but Ron still remembers this conversation vividly. From that day in 1961, Ron knew that this was the man he wanted to play for. ‘Shankly made me feel like a million dollars,’ Yeats says, smiling.

The threads of memory of those times are the ones that have not been so frayed, though St John is needed to relate how it was. You can tell Yeats is reliving some of Shankly’s messages in his mind, while nodding and smiling at his friend who talks about Shankly’s instructions: ‘Enjoy yourselves, keep the ball moving, and when you’re not moving, hold on to the ball and just remain positive; and don’t forget to have fun during the game.’

‘Ronnie was a very encouraging captain,” St John adds. “Some captains bark at their players but he would encourage us instead: “Come on, lads!” Of course, if we gave our opponents more room than we ought to, he’d let us hear it, there was never any doubt he was the boss on the pitch.’

Then Yeats looks up at his friend and smiles cunningly. ‘Will you tell the story about the Queen?’ At the time the May 1965 final was perhaps the most momentous occasion in Liverpool’s 73-year history. Ron Yeats was ready to climb the steps and receive the yearned-for trophy from Queen Elizabeth herself. During the last minutes of the game he had been wondering what to say to her. A few days before the match he had received a phone call from Buckingham Palace, and been instructed – should Liverpool win – not to address the Queen until she had talked to him, and that he had to say ‘Yes, Ma’am’ and ‘No, Ma’am’. Yeats had corrected the palace staff member by saying, ‘You mean when we win the cup, not if!’

Extra time had been played in pouring rain on a heavy pitch. The players were shattered as they walked up the steps to the royal box at Wembley. Ronnie wiped his hands on his clothes before he reached the Queen, who was ready to present him with the trophy.

‘You must be exhausted,’ Queen Elizabeth said to Yeats. ‘I’m absolutely knackered!’ ‘I’m certain that you are,’ the Queen said, and gave him the cup.

The men on the sofa are now roaring with laughter, thinking back to the conversation fifty years earlier.

Yeats was the first Liverpool captain to receive the FA Cup. He was so tired he had almost no strength to lift the trophy, but he did. And as he raised it and looked over at the sea of supporters, the shouts of joy that met him sounded as if it came from a million people. It was the sound of life itself.

Football in the 1960s has left its legacy too. An alarming number of former players now struggle with dementia. It cannot be a coincidence that so many former professional footballers from the 1960s and early 1970s struggle with the same diagnosis as Yeats: Alzheimer’s disease.

‘The football itself was incredibly heavy,’ Yeats says, ‘especially when it was wet. When you headed it... Most of the times you headed it you’d just think Jesus Christ! It’s almost impossible to imagine.’

‘The ball was like a medicine ball, like the big, heavy balls from PE,’ St John adds.

Yeats becomes serious. ‘You just had to make sure you hit it with your forehead. If it hit any other part of your head... Oooh, the headaches you’d have after a game...’

St John helps him out. ‘They never understood that back then. Today people realise the serious consequences of blows against the head like that. And remember, back then the ball was played a lot more up in the air. The wings would send cross-field passes, and as attackers we’d often crash our heads into the defenders’. There could be elbows involved too, and I was often accidentally hit by goalies. Knocks like these have caused problems for a lot of players.’

Yeats still lives and breathes the games, notwithstanding. ‘Oh yes! Before a game I’m always nervous on behalf of the team, and when they lose it gets to me,’ he says. ‘Then maybe I think what I would have done differently. But I keep that to myself.’ Ron Yeats smiles.

Liverpool Captains (deCoubertin) by Ragnhild Lund Ansnes is out now.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments