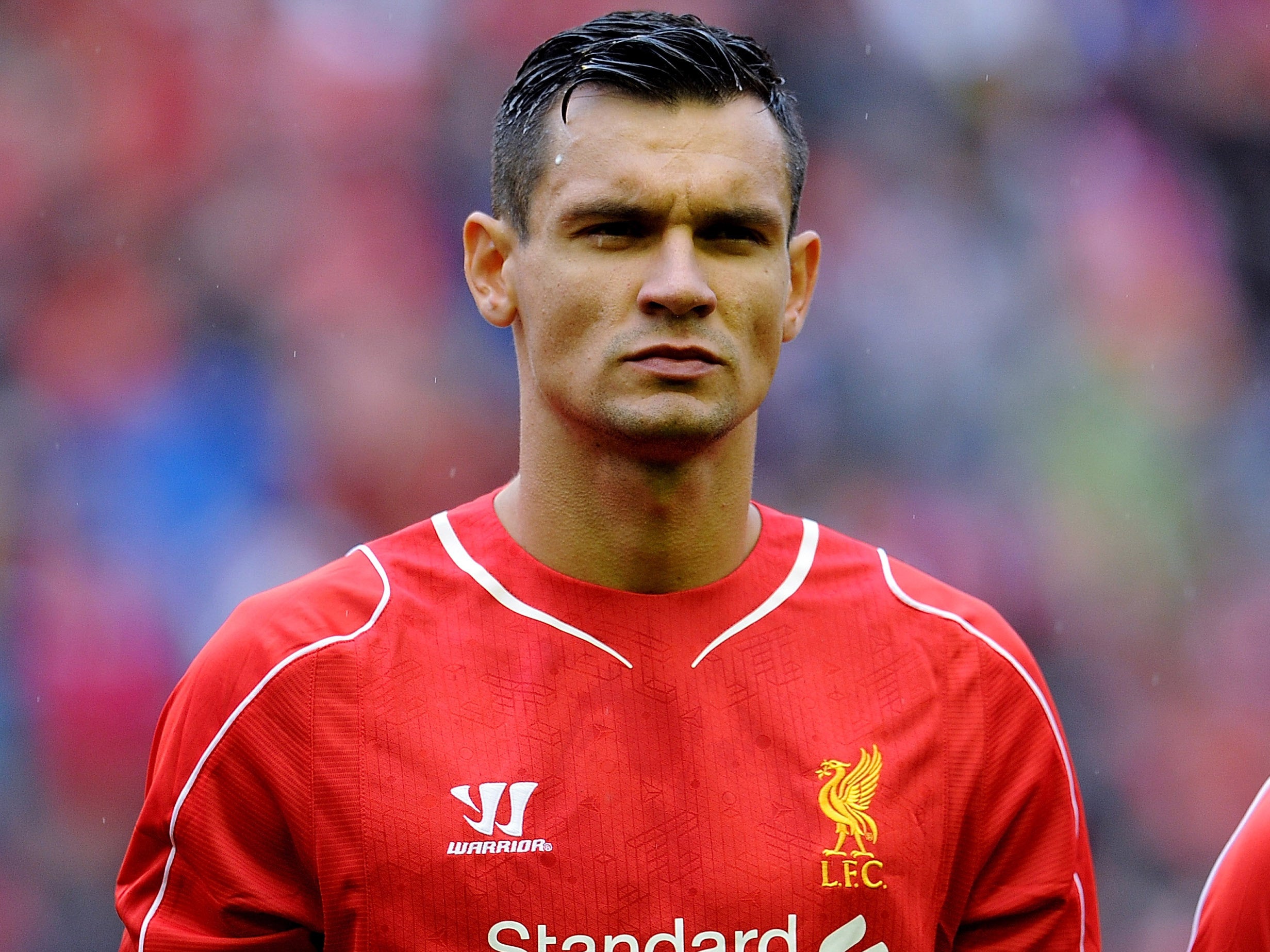

Liverpool's Dejan Lovren on being a refugee: 'I know what some families are going through, give them a chance'

Lovren escaped from war-torn Bosnia and was kicked out of Germany before settling in Croatia

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Liverpool’s Dejan Lovren provided a searing insight into the fear and dislocation of refugees on Wednesday night, describing his family’s desperate 17-hour overnight escape from war-torn Bosnia and urging those who are implacably opposed to welcoming those fleeing conflict to think again.

In an extended interview for a documentary screened on the club’s in-house television station, Lovren described the routine deaths which Yugoslavia’s ethnic conflict brought – his uncle’s brother was killed in front of others with a knife; a schoolfriend’s father died in armed combat – before the family fled to Germany, having emerged from a night sheltering from bombing raids in an underground basement, in 1993.

“When I see what’s happening today I just remember my thing; my family and how people don’t want you in their country,” Lovren said. “I understand people want to protect themselves, but also people don’t have homes. It’s not their fault; they’re fighting for their lives just to save their kids. They want to go away and have a secure place for their kids and their futures.”

Lovren tells the documentary makers how the modesty and tranquillity of the family’s home village of Kraljeva Sutjeska, offered no protection, even though the neighbouring Bosnian city of Zenica incurred greater bombardment. “I just remember when the sirens went on,” he said. “I was so scared because I was thinking ‘bombs’ or that something will happen now. I remember my mum took me and we went to the basement, I don’t know how long we’d been sitting there, I think it was until the sirens went off. Afterwards, I remember mum, my uncle, my uncle’s wife, we took the car and then we were driving to Germany.”

The family had been considering since 1992 the idea of fleeing to Germany, where Lovren’s father and mother's parents had already located. On 19 April 1993, the marketplace at Puticevo, nine miles from Zenica, was shelled, leaving 15 dead and a further 50 injured. Emerging from the basement, they placed family belongings into a few bags, threw them into their tiny car and left.

The escape was so sudden that they could not secure the paperwork which would grant them permanent exile. The three-year-old Lovren’s grandparents did possess the vital documents, because they had taken flight three years earlier. But though the young Lovren couple worked – Sasa putting in long hours as a cinema worker and Silva in a hospital – they were permitted only to extend their stay by one year at a time.

Lovren described two years ago how the initial experience in Germany, not speaking the language and knowing nothing about the country, was akin to being “like a blind man”. In the documentary, he relates how “my mum… was always crying and crying, and I never understood that. I was sometimes angry, always, ‘Why mum? Come on, stop it, it’s finished, we are here now, everything’s safe.’ But you know, I never understood it… I would say we had luck - me and my family - we had luck. We had our granddad who was working before in Germany, and because of that he had the papers to say, ‘yeah, come to us…’

“I remember we came to my granddad’s house. It was a little wooden house. It was so small but it was full of love – 11 of us lived there for three years. My mum said that every night, around 10pm, they switched on the radio and everyone listened to the news. My uncle’s brother was killed in front of other people with a knife. I never talk about my uncle because it’s quite a tough thing to talk about, but he lost his brother, one of my family members. Difficult…”

Lovren, like his brother Davor, grew into German life. He spoke the language, took the metro to the Bayern Munich training ground, aged six or seven, had his photograph taken there with Giovane Elber, Mario Basler and Bixente Lizarazu, dreamt of playing for the club. But the family's borrowed time in Germany ran out and in the depths of winter 1999 they experienced a form of deportation, back to Karlovac, south-west of Zagreb, in the land from which they had fled. The documentary provides the sense that, after seven years within the German education system, this was the worst dislocation of all.

“I spoke Croatian but not the proper Croatian,” Lovren said. “The right words and everything - so when I came at 10 to Croatia it was difficult. I didn’t understand, I didn’t know how to write, everyone was asking me, ‘why is your accent different to ours?’ and even today I have that German accent in my Croatian.

“It’s the age of 10, and you understand everything, you see everything what’s happening around you. The kids were just having fun, they didn’t mean to hurt my feelings on purpose, but for me after everything I went through it was a problem for me, and of course I had problems in the school because of that. Something in me didn’t allow for people to laugh about me, and then I had the school fights – I was fighting, I was fighting. I will fight until the end, that’s me. The teachers explained that, ‘he’s come from another country, you need to have more understanding.”

His mother worked in a Walmart store for €350 per month (£280) a month, while his father found employment as house painter. It was the day that Sasa Lovren took away his son’s ice skates that left the boy’s most vivid memory. He had sold them for 350 Croatian Kuna (£40) as part of the struggle to make ends meet. “My ice skates. Sold just to make the last week when the payment comes again.”

Lovren estimates it took him two years to learn his own native tongue. Playing football more seriously became a way "to try and fit in" and he impressed enough with youth teams of the local NK Karlovac club to be asked to join Dynamo Zagreb, 30 miles away. He began as a striker, only moving into central defence at the age of 16, but when the game took him out on the open road across continental Europe again - he selected Lyon over Chelsea in 2010 - there was another difficult chapter. There never seemed to be much appreciation of him in France. Eventually it was England – Mauricio Pochettino at Southampton and Brendan Rodgers at Liverpool – who valued him.

In Liverpool, he has found a city which built a rich history around the welcome it has afforded to so many of the displaced who arrived through its port gates. But to those many on these shores who would close their doors and their minds to those immigrants who seek asylum from civil war, he offers a perspective.

“I went through all this and I know what some families are going through,” he said. “Give them a chance, give them a chance. You can see who the good people are and who are not.”

"Lovren: My Life as a Refugee" can be viewed, free to air, at LFCTV GO (LiverpoolFC.com/video)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments