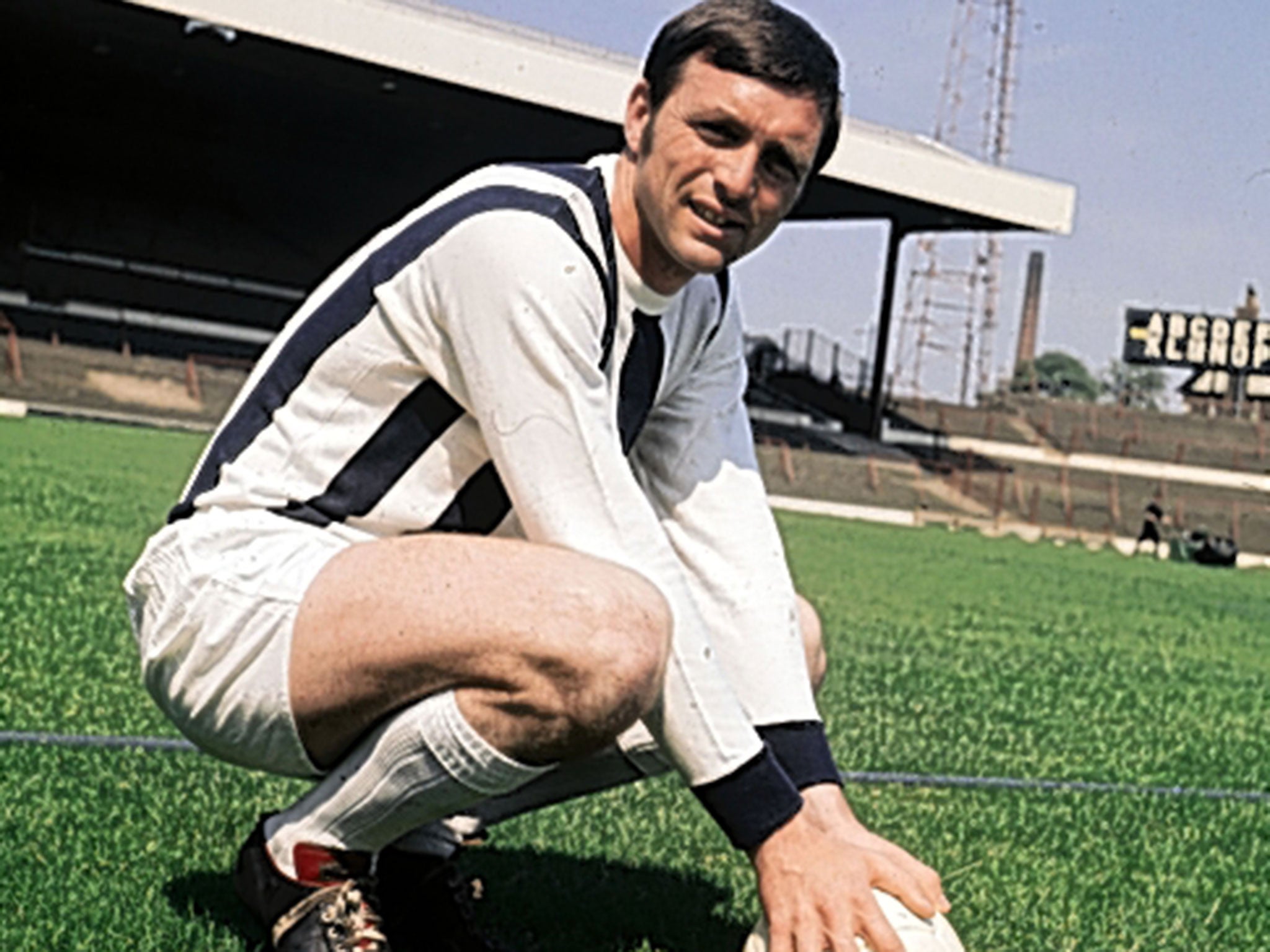

Jeff Astle Day: 'Jeff died not knowing he'd been a footballer'

Jeff Astle was a West Bromwich Albion legend yet died aged just 59 from a degenerative brain disease due to heading the ball. Simon Hart talks to his family about their campaign to help protect players in the future

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.“He always said his proudest moment was that goal. He said he felt so happy he could leap over the stands.” Laraine Astle is looking at the black-and-white photo, hanging in a golden frame, of her late husband Jeff’s winning strike in the 1968 FA Cup final.

Jeff Astle scored 174 times in 361 games for West Bromwich Albion between 1964 and 1973, but that goal against Everton under the old Twin Towers was the one that secured him legendary status in the Black Country – and it is a goal that will be remembered once more at a sold-out Hawthorns tomorrow when his former club celebrate Jeff Astle Day.

Albion’s players will take on Leicester City wearing a replica of their 1968 Cup final kit – the same plain white shirts and shorts and red socks – and five of Astle’s Wembley team-mates will be present. Yet the sweet smell of nostalgia will be offset by the painful fact that the man who secured that long-ago triumph – scoring in every round along the way – died remembering not a thing about it.

As his daughter, Dawn, tells The Independent, with another glance at the photo on the wall of the family home in the Derbyshire village of Netherseal: “Mum used to try to jog his memory with it, and say, ‘who’s that?’. He didn’t know he’d ever been a footballer. Everything football gave him, football took away.”

This is the reason why the Astle family – Laraine, her three daughters, five grandchildren and great-grandson – will be at the Hawthorns tomorrow. As well as celebrating the past, they will be there to launch the Jeff Astle Foundation, the next step in their tenacious efforts to stir the football authorities into acting on the lessons of the former England World Cup striker’s tragically early death following a four-year decline into the darkness of dementia.

After Astle died, aged 59, in January 2002, the inquest coroner ruled that he had suffered “death by industrial disease”, his brain damaged by the repeated heading of heavy leather footballs. It led to one obvious question – who else? Yet were it not for his family’s Justice for Jeff campaign, the Football Association and Professional Footballers’ Association would still have done not a single thing about it.

It was in March last year that Dawn and her younger sister, Claire, first unfurled their “Justice for Jeff” banner at an away game at Hull City. In the same month, the family arranged for Dr Willie Stewart, a consultant neuropathologist at Glasgow’s Southern General hospital, to re-examine Astle’s brain tissue. He found that Astle had suffered not from Alzheimer’s disease but chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a progressive degenerative disease of the brain found commonly in boxers.

“He scored more with his head than his feet,” notes 68-year-old Laraine, and it took a terrible toll. “Dr Stewart said if he hadn’t known Jeff was 59, he’d have said it was a man in his 90s. The central membrane had disintegrated.”

“We had started ‘Justice for Jeff’ before we knew Dad had CTE,” adds Dawn, 47. “It was purely to get the football authorities to do what they should have done. We then found out in an email from the FA that they did start research but unfortunately it collapsed.”

The FA and PFA had said back in 2002 that there would be a 10-year study to investigate the risks of heading a ball but, as Dawn explains, the “30-odd” youngsters involved did not progress into the professional game and “nothing was ever done since”.

By comparison, the University of Turin studied 7,325 players of different ages when seeking a connection between participation in the professional game and another neurodegenerative disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), commonly referred to as Lou Gehrig’s disease after the New York Yankees baseball star who died of the disease, aged 37, in 1941.

It has taken the Astle family’s campaign – at every Albion home game this season his photo has appeared on the big screen in the ninth minute (he wore No 9), followed by 60 seconds of applause – to provoke a belated response.

The FA chairman, Greg Dyke, wrote a letter of apology to the family and met them, accompanied by Dr Stewart, before the Community Shield in August.

“One of the first things he said to Dr Stewart was, ‘what do we need to do?’,” says Dawn. The wish of the newly established foundation is to see proper independent research as well as revised guidelines on dealing with head injuries for the grassroots and amateur game (as happened with the Premier League last summer). Yet while Dr Stewart has been invited on to an FA panel of experts, “this panel hasn’t met yet and we’re nearly at the end of the season”, notes Dawn, with a note of scepticism.

A meeting last September with Gordon Taylor at the PFA – organised with the help of Gary Neville, a patron of the foundation along with Gordon Banks, Barry Fry and comedian and Albion fan Frank Skinner – has led to more immediate action. “We said, ‘you haven’t done enough’, and since then they have been brilliant,” she adds. “They helped us set up the foundation.”

The foundation will also try to support those former players and their families now suffering as the Astles themselves once suffered. Heart-rending testimonials from the loved ones of other ex-footballers with dementia feature on the foundation’s website and this is just the tip of the iceberg, according to Dawn, who says, citing one example: “The daughter of Johnny Dixon, Aston Villa’s 1957 FA Cup-winning captain, rang to say, ‘my dad had Alzheimer’s and my mum always said she thought it was something to do with heading the ball’.

“Easily 90 per cent of the people I speak to are either centre-halves or centre-forwards. People say it might have been a problem with the big heavy ball in those days, but if you speak to Dr Stewart he will say there’s no evidence to say the modern ball is any safer. It is still having something smashed against the skull. I had a footballer ring me who had just been diagnosed with early onset Alzheimer’s – he’s only in his 50s and played in the 80s, a centre-forward. He was saying, ‘what do I do now?’. There needs to be a proper system for support.”

The foundation’s ultimate goal is a care home for sports people suffering from dementia, and their fundraising will be boosted by an auction of the special kits Albion’s players are wearing this weekend.

For Dawn, this season’s ninth-minute ritual of remembering her father has brought mixed emotions – “it reminds you that your dad has died every week” – yet she is grateful for the support of fans and clubs across the country, noting how rivals Aston Villa and Birmingham City both displayed her father’s image on the screens at their stadiums when Albion visited. Tomorrow’s match – at which the grandson Astle never met, two-year-old Joseph, will be the mascot – promises another whirl of emotions.

“It is going to be a mixture of laughter and tears – Jeff would certainly want the laughter,” says Laraine of a man better known to a younger generation for his comic singing on the Fantasy Football TV show in the 1990s.

For Laraine, though, the sight of those shirts will take her back to London’s Park Lane Hotel and the moment she greeted her Cup final hero. “Jeff walked in with his bag and his boots,” she recalls, her voice breaking with emotion. “There was no need for words. He just smiled as if to say, ‘I did it’ and we hugged in complete silence. He’ll be there. I know that when little Joseph walks out, his granddad will be holding his hand.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments