James Lawton: Will Spain join the immortals? One day perhaps, but not until they bring more goals

Great teams tend to score lots of goals in different ways. The brilliant Brazilians of 1970 tallied 19. But in South Africa, Spain scored just eight goals

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Sometimes in football, as in life, we should really know what we are celebrating. If this is true it was maybe rarely more so than here on Sunday night, when so many high-profile pundits seemed to think that Spain not only deserved to win their first World Cup – which they unquestionably did by any kind of measurement you wanted to make – but were also worthy of depiction on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

The assessment was so far over the top it might have been wearing an Oranje jersey.

So let's give to Spain everything belonging to them, indisputably – and keep back that which we should always reserve for the truly great teams.

The tribute they deserve most is that they have created a wonderful football culture, so generous in its spirit and full of ambition to confirm their belief that winning is fine but should always be achieved in a certain way.

They have produced players like Andres Iniesta and Xavi Hernandez – the sentimental vote for Diego Forlan in the Golden Ball Award was an understandable tribute to such a full-hearted player but, of course, the pick of the tournament surely lay between the men who drove the Spanish midfield – who seem, when it matters most, to be impervious to the forces of celebrity and wealth.

They play with a passion and a commitment against which the efforts of teams like England and France, particularly, were made to seem like the shuffling of the morally dispossessed.

Cesc Fabregas, who again had to settle for a marginal role, exposed the vapid frustrations of the English camp in just a few asides before the start of the tournament. No, he wouldn't be fuelling a selection debate. He was at the service of his country and he would respond if the call came. His duty was to train, to work and give his country a month or so of his life.

In his moment of triumph, the old walrus Vicente del Bosque said that his team's success had gone beyond the borders of sport. It had animated a proud nation, a task in which England coach Fabio Capello started so promisingly but ultimately failed. This was partly, no doubt, because when the competitive crunch came his touch on the international stage was to be much less assured than the one he brought to the stewardship of some of Europe's leading clubs. Hugely significant, and obvious though, was the failure of England's players to begin to grasp the nature of the challenge the Spanish players have engaged so brilliantly and for so long.

In reviewing the Spanish performance here yesterday there was, apart from the complication of the Netherlands' deeply cynical and brutal performance and the fact that Spain did not always behave like those characters flying around the roof of the Sistine Chapel, an almost overwhelming dose of déjà vu.

In Vienna two years ago we saluted new champions of Europe, who had created not just a special style of play but an intense communal spirit. A year last spring in Rome we celebrated the core of the Spanish side in Barcelona's masterful defeat of Manchester United.

Now we can still look back on Spain's supreme triumph with some moral certainties.

We can acknowledge again the fact that the most distinguished player the Netherlands has ever produced, Johan Cruyff, has made no secret of the fact that, if his blood is Dutch, his football sympathy is largely with Spain.

We can say that of the two teams who brought the 19th World Cup to a close only one was truly interested in winning through the strength, not the perversion, of their football nature.

Yet having said this, and also noted that the best Spanish performance came not in the final but in the defeat of a young German team which were next best in the challenge of restating the worn-down belief that a World Cup should be the place where the game is most clearly seen to be moving in new and higher directions, we have to recognise another fact.

It is that if the new champions of the world's most popular game possess some of the finest qualities, they are not a great team, or at least not among the greatest we have seen.

There is an extremely basic reason, and it is one which no doubt influenced Jose Mourinho when he plotted the downfall of Barcelona in this year's Champions League. Barça and Spain have an identical midfield – and the same priorities. But Spain simply do not score enough goals.

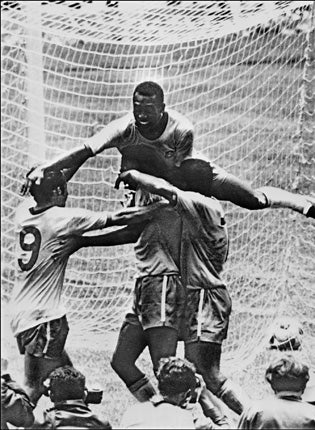

Great teams tend to score lots of goals, in different ways, and if we want a point of comparison we can remember how many Brazil scored in 1970 in Mexico, which is generally agreed to have been the greatest tournament of them all. It was 19, with just one of them coming in their epic group game with the reigning world champions, England, in Guadalajara.

Eight years ago the Brazilian winners, the palest version of the team of Pele, Jairzinho, Tostao, Gerson and Carlos Alberto, managed 18.

Here in South Africa Spain scored just eight goals, or just fractionally over one a game. It is why some of us, not guessing the depths to which the Dutch would compromise their own historic reputation for playing a superior version of the game, believed they were vulnerable on Sunday night. What no one could have suspected was that Spain would fall so short of the standards of creativity they had set for themselves.

In the end it was the bite and the nerve of Iniesta that made the difference, and then only after the besieged Howard Webb had somehow managed not to award a Dutch corner. Webb had a gruesome evening while trying to deal with the systematic infringements of the Dutch, but in some ways it was no less trying for Del Bosque.

Repeatedly, the Spanish coach was confronted by the possibility that his team's failure to score the goals that would have enforced their superiority had put everything at risk, as it had in the semi-final against the Germans who, though outplayed, managed to fashion the best chance of the night.

None of this is to question the legitimacy of Spain's No 1 place in today's football – or the splendour of a culture which in so many ways is so far ahead of its rivals.

The French Sports Minister, Roselyne Bachelot, surely envied the joy that swept into every corner of Spain at the moment of victory. After her meeting with the desperately underperforming French rebels she declared: "I told the players they had tarnished the image of France. It is a moral disaster for French football. I told them they could no longer be heroes for our children. They have destroyed the dream of their countrymen, their friends, their fans."

In England a similar message could have been passed on by Bachelot's counterpart, Hugh Robertson. England's players did not rebel, not if you don't count John Terry's brief and embarrassing hopping off and back on to an extremely rickety fence. But in all else they occupied an utterly different football planet to the one conquered by Spain.

Spain have shown what can happen when a special set of players, and supporting spirit, takes hold of a dressing room. It can make all the difference in the world. It can lift the nation's idea of itself. It can begin to justify the vast rewards that come to the best footballers, because they are giving something back, some sense of responsibility and ambition to make beautiful football – and beautiful moments.

What it cannot do, necessarily, is make one of the greatest of football teams. You may say that you cannot do better than win the World Cup, but of course you can. You can win it in a way which no one will ever want to forget.

Pele's Brazilians did it in 1970. Maradona provided his own version in 1986, when he scored five of Argentina's 14 goals, albeit one of them illegally. However much we want to celebrate a moment, and recognise virtues that are exceptional in today's football, we cannot say that Spain did it here.

They underpinned a brilliant culture with victory. They were, at least most of the time, on the side of the angels. But did they achieve true greatness in Soccer City? No, they did not. It has to be their next challenge and, who knows, it might be their final gift to a game already deeply in their debt.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments