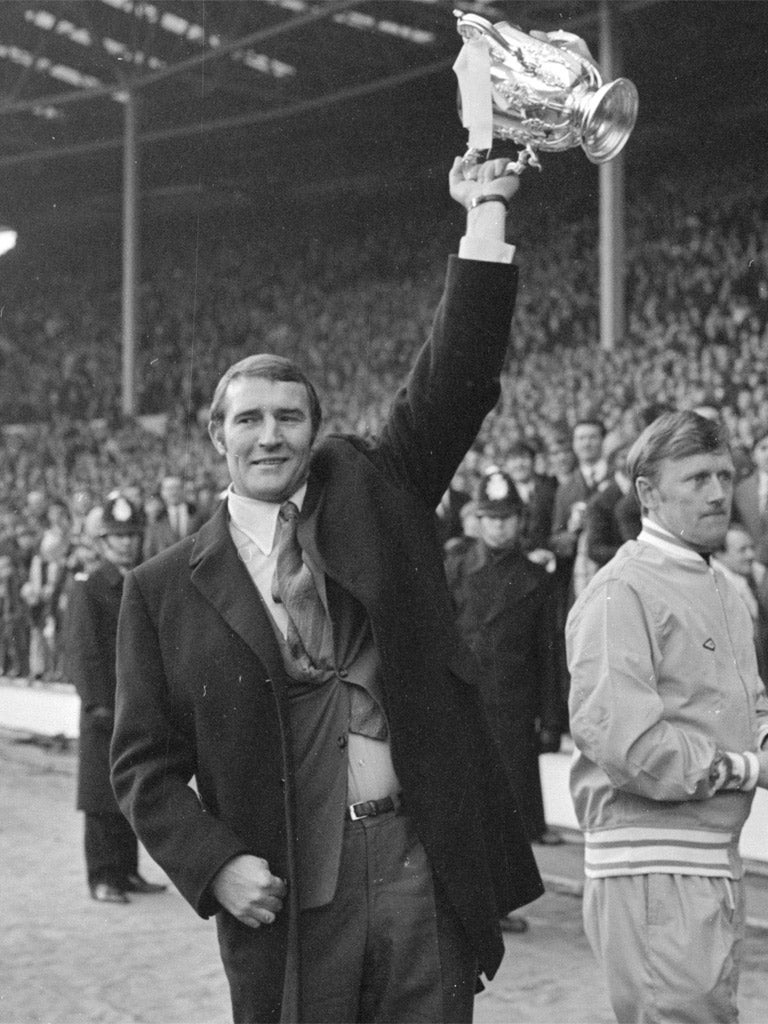

James Lawton: Last City side to win the title blazed all too briefly as Big Mal's magic burnt out

‘Next stop Mars,’ said Allison back at Maine Road the morning after City won the title

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Yaya Touré's declaration that Manchester City may well be about to rule the world is only excessive if you forget, or were not around, the last time his club became champions of England.

Then, 44 years ago, Malcolm Allison, the brash but exceedingly brilliant young coach empowered by a wise old Joe Mercer to transform the embattled club, was certainly more bullish than the big man from the Ivory Coast.

Big Mal celebrated a superb title end-run which saw City win with stunning panache and nerve at Tottenham and Newcastle with a claim that was always bound to leave Touré's relatively practical ambition decidedly earth-bound.

"Next stop Mars," said Allison back at Maine Road the morning after Newcastle had been overwhelmed 4-3 on their own ground. For starters, City would terrify Europe.

He had a bottle of champagne in one hand, a Havana cigar in the other; his other possession, apart from a rumpled suit and a monumental hangover, was a constantly re-chargeable self-belief. It easily negotiated the derision which came a few months later when City were ejected – in a blaze of re-printed headlines – from the first round of the European Cup in Istanbul.

No, City did not get into space and their highest achievements were to win in the next two years the FA Cup, the League Cup and the European Cup Winners' Cup on a rain-sodden night in Vienna.

In football terms it was a brief run across the face of the sun but if the modern City look so much better equipped, in resources and some exceptional manpower, to establish a genuine dynasty, we should not stint in our remembrance of their forerunners.

They could not keep their high trajectory. They broke apart and when a conspiratorial takeover group – operating under a code phrase, "The sun is rising over Maine Road", that was hard to say with a straight face – pulled their coup, a saddened Mercer asked: "How is it possible to hijack a club in full flight?'

Too often it seemed too easy but if City were soon enough obliged to yield again the high ground to powerhouses like Leeds and Liverpool, the new force of Brian Clough's Derby County and Double-winning Arsenal, no one could say they had not seen them pass by, lighting up the sky with the adventure of their football and the sharp edge of their character.

It started in the summer of 1965 when Mercer, his nerves frazzled by a tempestuous time at Aston Villa, accepted the job of guiding City back to the First Division only on the condition that he could sign the arresting young manager of Plymouth Argyle.

It was not a case of like seeking like. Mercer, amiable and puckish, was a statesman of the game; Allison, soon enough, would be derided as an "embarrassment to football" by Leeds' Don Revie. But Mercer saw something extremely rare, even unique in English football at that time, in the former West Ham player whose career had been cut short by TB and whose philosophy of life was once expressed while he lay gasping for breath on the Sheffield Wednesday pitch. "It occurred to me," said Allison, "that I had £50 back in the dressing room and there was a very good chance I wouldn't get to spend it."

He was a professional gambler for a while, ran a club in London's "Tin Pan Alley" – where one night a young Jimmy Greaves agonised over whether he should leave Chelsea for a new life in Italy – coached Cambridge University, and then, via Bath City, made a stir at Plymouth, both on and off-field, his riotous private life not exactly strengthening his position. However, in the West Country he also rediscovered his passion for football and saw in Tony Book, a part-time full-back and stonemason and future Footballer of the Year, a natural born leader.

City won promotion at the first attempt, solidified for a season, then broke from the traps with a swagger that foretold their impending status as champions. Mike Summerbee, Colin Bell and Francis Lee – the great triumvirate – were signed for a total of £130,000. Mike Doyle grew as fast as a bamboo shoot. Alan Oakes, who Allison noted had a disconcerting habit of sweating profusely before every kick-off, became a dominant midfielder and the tall elegant local boy Neil Young became a player of beautiful accomplishment.

Leeds were not noted for overflowing generosity but when City had come and gone as a major force, the ferocious field general John Giles allowed: "City didn't stay around too long but for a little while they were the best – under Allison they were given a set of brilliant football values."

They also enjoyed themselves immensely. At dawn following the Cup Winners' Cup win in Vienna, Allison was found on the balcony of his hotel bedroom, airily waving to the old city and announcing: "This morning I feel like Napoleon."

A little earlier Lee, clad only in his underpants, had been sighted dancing on top of a piano.

So what unhinged this joyous team? As much as anything it was the frustration and impatience of Allison. He believed that he had a promise from Mercer that he would soon acquire the full trappings of manager rather than those of the high-achieving but still prodigal coach. He had turned down an offer from Juventus and believed that he had been let down at City.

In truth he made two costly miscalculations. He gave his support to the takeover group and cut himself loose from Mercer, a severance that left him more vulnerable than ever to his own most reckless impulses. He also craved the charisma of the United of Best, Law and Charlton. They had been beaten on the field but not surpassed in glamour.

So in the spring of 1972 he signed Rodney Marsh for a club record £200,000. Over the years Marsh's extravagant skill would endear him to City fans but it was a short-term disaster. The dressing room was split, Lee being especially irritated by Marsh's arrival there in an old leather coat, beads and open-toed sandals.

A four-point lead at the top of the First Division evaporated. Mercer moved to Coventry City, Allison to Crystal Palace.

Seven years covered it all, the new and wonderful ambition, the searing football and the enveloping sadness. It was over too soon, no doubt, but then isn't it true of so much that shapes the best of a life, and, certainly, a football club?

Luxembourg fight would be fresh blow to boxing's battered reputation

Under the risible aegis of the Luxembourg board of boxing control, the organisers of the proposed fight between David Haye and Dereck Chisora have made claims guaranteed to turn the stomach.

Chief among them is the suggestion that a "proper forum" is required for them to settle their differences. This suggests that Haye and Chisora have between them so far provided anything but a travesty of decent sporting values. So a proper forum for what, precisely, is being advocated? It is, we can only presume, for the legitimising of behaviour that would arguably bring a routine conviction if it occurred on the most wretched of the weekend binge streets of our cities and towns.

Of course, there is another more basic explanation. It is the exploitation of public gullibility for the most disreputable profit. Frank Warren is an intelligent man of considerable charm and for some time he has been Britain's leading promoter of boxers. His presence at the heart of this apparently unstoppable abomination is thus rather more than dismaying.

It marks the lowest point of British boxing in this particular lifetime.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments