James Lawton: Ferguson feels Old Trafford sands shifting beneath his feet

Rooney's desire to walk away leaves United manager cast in the unlikely role of victim

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It may still be a little too early to dismantle the stage at the Theatre of Dreams but if you wanted to find the face of changing times yesterday it was the one owned by Sir Alex Ferguson.

You had to go back to the sheepishly backheeled goal by one of their greatest heroes, Denis Law, that briefly condemned them to the wilderness of the old Second Division at, of all places, Manchester City's Maine Road, to find a time when Manchester United had been so roughly thrust into an uncertain future.

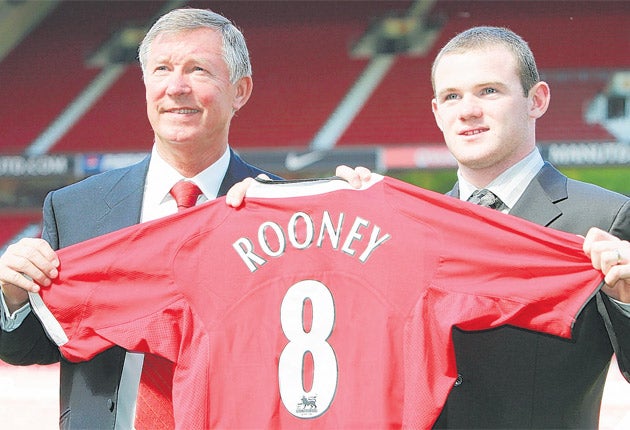

Ferguson looked pained and more than a little bewildered when he announced that, yes, it was true, Wayne Rooney had made himself available to the highest bidder, had decided that United was, all of a sudden, someone else's dream and paymaster.

The strongest word is that Rooney, like his former team-mate Carlos Tevez, will soon enough be wearing the light blue of City, the club who may, finally, have achieved the ambition which so many times they have been forced to believe United had proofed against all threat and possibility.

Back in the Fifties the tactical improvisation of City's Les McDowall, who borrowed his Revie Plan of a withdrawn centre-forward from the brilliant Hungarians and had the phenomenal goalkeeping of Bert Trautmann, won an FA Cup but it couldn't begin to impinge on the momentum of the Busby Babes.

The Munich air tragedy threatened the very existence of United but it was quickly apparent that, with the likes of Bobby Charlton, George Best and Law, they would become strong at the broken places.

When the superb partnership of Malcolm Allison and Joe Mercer conjured the league title for City in 1968, the euphoria lasted only for the few days before United won their first European Cup against Benfica at Wembley.

Now, though, the end of all the years City have had reason to believe they were attempting to scale Mount Eiger in carpet slippers may well have been signalled by the Ferguson grimace and the forlorn admission that he had failed to persuade Rooney that his future lay at Old Trafford.

If it is true, if Rooney is indeed about to inhabit the Ali Baba cave of City's Arabian wealth, Ferguson knows well enough that he cannot expect the smallest wave of sympathy outside his citadel of Old Trafford – one that in the realities of football, which in today's game are shaped so hugely by random wealth, has never looked remotely so vulnerable in the era of the Premier League.

Ferguson for so long has exploited, with a shameless but brilliant ruthlessness, every advantage that has come his way. Some of his most celebrated servants, Beckham, Van Nistelrooy, even his alter ego Roy Keane, have felt the force of his judgement that, one way or another, they have outlived their usefulness. Yesterday we had another and entirely different picture. It was of Ferguson no longer the master of all he surveyed, no longer the man who turned almost every situation to his advantage, but one stretched and harried by new and unfamiliar circumstances.

Ferguson, the most successful manager in the history of English football, was plainly, and at least for a little while, cast in the unlikely role of victim.

Victim of the constraints imposed upon him by the bizarre situation of United, one of the game's ultimate cash cows, painfully crimped by a debt load unimaginable in those days when he was converting them from a club up for auction at around £13m into a juggernaut concern valued at close to a billion. A victim, also maybe, of Rooney's need for support in the self-imposed disasters of his private life that a ferocious old professional found impossible to provide.

Most of all, though, you have to suspect, Ferguson has suffered most from a dividing line that has never before been quite so arbitrary; the sheer scale of the wealth available elsewhere to a footballer in his mid-twenties who, you might have thought, had already acquired spending power beyond his dreams.

Yes, of course, there is a supreme irony here in that for so long Ferguson had every reason to believe that he could straddle that dividing line with hardly a care in the world.

He could beat down the doors of White Hart Lane and come away with Dimitar Berbatov. He could speculate on the potential of Cristiano Ronaldo at a give-away £12m. He could snap up Rio Ferdinand.

Now he has to look into the unyielding face of a Wayne Rooney, who despite the horrors of his recent experiences on and off the field, has the unbreakable understanding that at City he could snap his fingers for more than the near £200,000 a week already obtained by the strong but scarcely comparable Yaya Touré.

We know how Ferguson will handle any of the consequences that flow from his current crisis. He will fight on, talking up the best that he has left and treating any challenger to his position as just another outrageous imposter. It is the way he rose and, we can be sure, it will be the way he goes down, if that is indeed his fate.

He knows, of course, that nothing is guaranteed in football, and certainly not to City, who have been cast as his most likely tormentors, if they pay something like £100m for a player who in recent months has not exactly provided cast-iron evidence of the durability of his talent or the stability of his character.

The trouble, for Ferguson, is that he knows that when all is right with the prodigy who left Everton, his beloved Everton, with scarcely a backward glance, Rooney is capable of doing anything he likes on a football field. He carries the mystique and all the possibilities of natural-born genius.

That, be sure, is what burrowed deepest behind the haunted expression of the Manchester United manager yesterday. Such players as Rooney and Ronaldo are not supposed to walk away from Old Trafford. At least it was so before Wayne Rooney told Ferguson, with such shocking abruptness, that the football world had changed – and might, for him, never be quite the same again.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments