Ian Herbert: Uncelebrated and unknown: The genuine story of George Best's babysitter

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

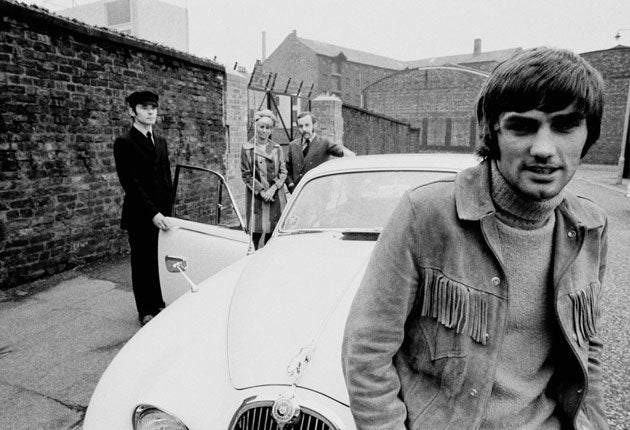

Your support makes all the difference.It is prurience that tempts you to reach for Celia Walden's Babysitting George from the bookshelves; an itch to know how the scion of a distinguished political family – and the Daily Telegraph – could have conspired to antagonise all those women George Best left behind to the point of uniting them.

It has almost been lost in the nest of spite, generated by Walden's "memoir" of her brief time "minding" Mail on Sunday columnist George Best for her editors at the paper, that it will be 50 years next month since a skinny, 15-year-old Irish kid first arrived for a trial at Manchester United.

The elegant marketing of Bloomsbury offers some hopes from Walden's book, which sits there among the recommended Father's Day offerings that will greet visitors to bookshops this weekend, and beyond the evocative image of an old pair of battered boots on the dust jacket there are certainly some degrees of revelation. Walden discerns, for instance, that Best nursed an indignation about the perception that all footballers are dim. ("I would use books to escape on long coach journeys or fill in the time at hotels, but do you think anyone's going to care what I think?") We also now know that George Cockcroft cult thriller The Dice Man is one of the last books he read, though Walden's piercing power of observation expects you to spell out that it was written in 1971. Best lived in his glorious past until the end and Walden does spot the present tense when he says plaintively to her: "Do you really think because I'm a footballer, I'm thick?"

Her depiction of an alcoholic's capitulation is also as masterful, in its own way, as her dissection of the small physiological progressions towards death: the leaden eyes and the swollen ankles and the mouth do the talking, though never the feet. And neither is there an attempt to hide the gory details of the journalistic process. Most depressingly accurate is Walden's admission that Best wanted to be left to the surrender to alcoholism which he knew would kill him, and yet her newspaper kept up the coverage – only for as long as the public was titillated. "Easily palatable messes are great fun, but the newspaper-reading public aren't too keen on gory close-ups," Walden writes. "I understood this rejection of George ... Only the occasional flare-up from Planet George took me back."

Walden is a part of this malign process, though. Some doubt whether she actually spent any more than one week and a few hours in total with Best. "She conceals this with some wonderfully elastic phraseology," a dubious Private Eye suggested this week. It's tabloid kiss-and-tell, all right, except the juicy bits are dressed in so elegantly that you see exactly why the BBC fell for the marketing hype and made this its book of the week. "He pushed me clumsily against the door frame, threading a knee between my legs..."

All of which takes us a very long way from the book which really can claim to depict the art of Babysitting George but which you certainly won't find located on the Father's Day rack at Waterstone's today (though the Deansgate branch in central Manchester did find a copy in the basement on Tuesday). It is the memoir written by John Roberts, erstwhile of this journalistic parish, of his time as Best's ghostwriter for the Daily Express during the player's tumultuous period of United decline, between 1971 and 1973. The book, Sod this, I'm off to Marbella – a reference to Best's impulse decision to ignore United's orders and take a taxi to Manchester Airport to catch the first flight he fancied in 1972 – is built on rather firmer foundations, even though the similarities of the task he and Walden faced remind us how Best's life was one of history continually, miserably repeating itself.

Walden's mission was to join Best in Malta and stop him breaching his contractual deal with her title by blabbing to others about his marital breakdown. Roberts was detailed to join him in Majorca after that perennial failure to stop himself ruminating aloud meant the player had forgotten his contractual obligations to the Express and given a stunning "Best Quits Football" exclusive to the rival Sunday Mirror instead.

First published in 1973 and reprinted last year, Sod This... has none other than Best as an advocate, who says of Roberts' script: "This book's honest. You wouldn't have got through the door if it wasn't." The author was the man with whom Best shared his thoughts each week during those roller-coaster three years and to whom, the book reveals, he one week presented four sheets of neat, handwritten copy, complete with crossings out. He had decided to take up arms against criticism of gamesmanship from Newcastle United's players and Manchester City's Malcolm Allison and Francis Lee, and literally penned the column himself. "I was dying to go downstairs for a game of snooker but I managed to resist the temptation for long enough to get it done," Best told Roberts.

This particular column does not reveal a great deal more than how wrapped up in himself and the world's opinion of him Best often was. (Beyond the legend, Best's personality was often far less than attractive.) But those spiralbound sheets, faithfully reprinted, represent authenticity and are as genuine as many other incidental details discerned from a life lived alongside Best. His fear of swimming, for example: Best was aged 10 when a friend of his died while his family and others holidayed in Groomsport, Northern Ireland. He hoped that the heated swimming pool he had installed at Che Sera, his legendary house in Bramhall, Cheshire, might finally help him get over it.

Roberts' book tells us how the journalistic process has changed, too. It was as early as 1971 that Best told his amanuensis that he wanted to leave United, which would have been an incredible Express exclusive, but the player wanted an additional payment from the paper for the right to publish the fact. The Express said no. Some things never changed, though. The booze is there in Roberts' book, though unlaboured. Vodka was always Best's drink, despite suggestions at the time that he went after the whisky, and The Grapes pub in Manchester is where you would sometimes find him in the afternoon when, as always, he trooped off last from training at The Cliff. It was where you would nearly always find him, come the evening, after his sleep.

"George is not a fill-up, fall-down drunk," Roberts reflects on the Majorca weeks. "My guess is that the effect on his system is steady and cumulative." Understated and apocryphal, these words might have been Best's epitaph. But since they do not belong to the prurient and charmless obsession with laying bare every aspect of a celebrity's disintegration, they remain virtually unknown.

United initially banned Roberts' book and allowed perhaps 100 copies to be sold "under the counter" at the United souvenir shop. By a rich irony, the reprint was taken on last year by Trinity Mirror, whose publishing forebears clinched that "Best Quits" scoop from under the Express's nose all those years ago. It has sold a few thousand.

Hard road for Yardy even with sport's support

It has almost passed without notice that Michael Yardy's struggle with mental health problems persists. The Sussex captain is taking another break to resolve them and The Independent's story this week of the struggle undertaken by his team-mate Lou Vincent, the former New Zealand opener who ended up tiling the BBC's Media City at Salford after deciding that an enforced break on the other side of the world was the antidote, suggests a hard road ahead.

The ECB must take some credit for acknowledging the problem which afflicts a sport of extraordinary introspection. The diary of one season by the former Kent and Middlesex opener Ed Smith, On and Off the Field – one of the finest cricket titles of recent years – reveals how tortuous a sport this can be, and that from a player not affected. Geoffrey Boycott recently attempted to apologise for his initial comments about Yardy. "It is hard for my generation to understand," he said. "In my day if you were down or depressed we were just told to pull ourselves together." It is a mercy that Boycott is paid to commentate and not administrate the game.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments