Ian Herbert: Qatar World Cup in 2022 deserves to receive more perspective and less prejudice

Sport Matters: Of course the Middle East has the right to host a World Cup

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Well, this attempt to win global profile is working out well for Qatar. The World Cup they want to stage is still nine years away and the impression so far is of a steamy, unenlightened hole in the desert where they’re hot on courting sport’s power brokers and not so hot on looking after their foreign workers. That certainly was not on the brand manager’s PowerPoint presentation when he said a 2022 bid was a good idea.

You imagine that the burghers of Doha must be casting very envious looks at Abu Dhabi at the moment and wondering how on earth they do it. With the enlightened, imaginative way that emirate has run Manchester City, it has developed a reputation as a source of all things good, because the fervent emotion sport whips up struggles to get past the surface gloss. But though the feelings for the club’s owners are justifiably glowing at the Etihad – “Manchester thanks you Sheikh Mansour,” reads the banner paid for by fans which hangs across the Colin Bell Stand – Abu Dhabi has next to zero democracy, a censored press and a far worse human rights record.

Qatar, by comparison, has democratic institutions, is a hub of diplomacy in the region and has a heavily entrenched commitment to free speech – astonishing by Middle Eastern standards – which allowed Al Jazeera to establish itself in Doha and set the Arab media free. It’s a measure of how damaged Qatar’s reputation for probity has become since it won the right to stage the 2022 World Cup that I slightly hesitate to quote the description of its outgoing leader Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa al-Thani in this week’s issue of The Economist. Possibly “the most dynamic and charismatic Arab leader so far this century”.

And while there really are no words to capture adequately what has befallen Nepalese immigrant workers effectively imprisoned by the country’s state-run kafala sponsorship system – their testimonies this week called to mind the 30 wretched Chinese men I found packed into the filthy squalor of a terraced house in Liverpool soon after the 2004 Morecambe Bay disaster – this shame is not Qatar’s alone. Human Rights Watch has expressed similar concerns about the UAE, while the journalist James Montague, whose new book on Middle East football When Friday Comes is based on many miles travelled, has been writing about kafala across the region since 2006. Montague is certainly no apologist for Qatar. He broke the story about the plight of workers in the country for CNN four months ago. But he does believe that some perspective is required. “Yes, there’s been some bandwagon-jumping where Qatar is concerned,” he tells me.

None of this is to defend the indefensible – because the way Qatar secured the right to stage the 2022 tournament was also flawed beyond belief. The giddy ExCo members ignored what they should have considered – an official inspection report telling them that the summer heat was “high risk” – and considered what they should have ignored: politicians like France’s Nicolas Sarkozy who fancied getting their hands on some of those Qatari petrol dollars. But does all of that mean the Middle East has no right to stage a World Cup? Well, no one was complaining about the region when its sheikhs started throwing their millions at clubs everywhere – from Manchester City to Barcelona, Sheffield United to Paris Saint-Germain. Fifa’s notions of taking the “world game” to all parts of the globe is a sound one, even though aspects of that organisation and its leadership are so miserably unsound. Yes of course the Middle East, where football is viewed with messianic reverence, has the right to share in the festival. Qatar happens to be the requisite location because the alternatives have become so untenable.

Egypt would have been a good choice before the Arab Spring began unravelling. It is cooler, of course, with a football-playing culture that could have badly used the legacy of stadia and infrastructure. Brash Dubai was talking about a bid in 2006, though that idea collapsed when its economy went south. The divisions between the seven not-so united emirates – a get-together between the various royal lines would feel like an excruciating family get-together at Christmas – make a pan-UAE event impossible.

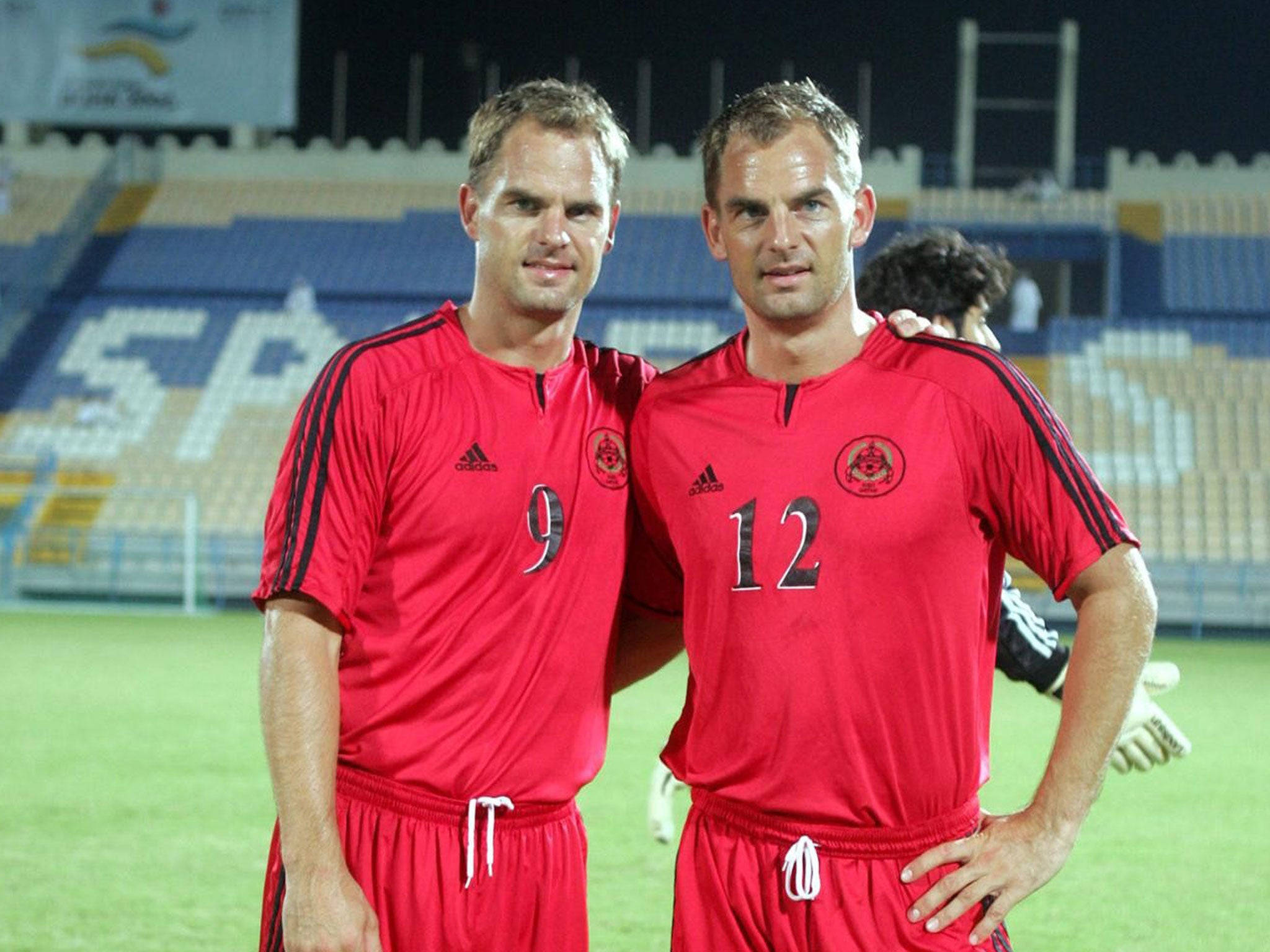

It is certainly a fairly sparse football culture in Qatar, with its population of barely two million. Montague’s book, a fine read, paints the memorably desolate picture of global stars and journeymen, from Marcel Desailly and Ronald de Boer to Paolo Wanchope and Jay-Jay Okocha eking out their last seasons in deserted Qatari stadia, though his prediction that a Qatar event will be a pan-Middle Eastern affair, with subsidised Qatar Airlines flights bringing the Middle Eastern diaspora to Doha, reflects the shifting diplomatic tides in the country. Thani has been succeeded by his 33-year-old son, Tamim – a man on a mission to fix Qatar’s reputation as the upstart of the Middle East and adopt a more pan-Arabian perspective. The Economist observes that it is Qatar’s new-found modesty under Tamim that has seen the 2022 World Cup now being sold as “an Arab event rather than a purely Qatari one”.

The paper also suggests that Qatari money may ultimately do the talking where the question of switching from a summer to a winter World Cup is concerned. There will be plenty of people complaining and demanding heavy compensation if that happens. As well as the Premier League and other members of football’s European hegemony, the US broadcaster Fox has tartly revealed that it agreed to pay $1bn for the rights to screen the World Cup in the summers of 2018 and 2022 – not in winter. But the Qataris have very deep pockets and may compensate the disgruntled handsomely if, as expected, the shift from summer to winter is ordered. It is a source of immense pride to Qatar that the event does go ahead. There is a huge amount of political capital invested in it. At such moments as this, the Qatar Investment Authority, one of the world’s largest sovereign wealth funds, doesn’t tend to flinch. It bailed out a fair bit of Britain after the financial crash of 2008, too, remember. One occasion when nobody was calling Qatar an unpleasant hole in the middle of the desert.

We’re not all heartless phone-hackers, honest...

A telling moment amid a few hours talking careers on Thursday night with the pupils at my daughter’s seat of learning– Manchester’s excellent Withington Girls’ School. “I don’t think my daughter’s nasty enough to do your job,” a mother told me, settling a frown on me. “I’m not sure it’s right for her.” This might have said more about me than anything, though it probably also reflected the damage done by the steady stream of hacking revelations, News International’s steadfast refusal to acknowledge them for so long, and the way journalists always seem to be characterised on TV.

“You’re allowed to be nice,” I told her daughter. “Don’t bother with a journalism degree. Talk to people. Make contacts. Read newspapers. Don’t get your stories from a Google news search.” She seemed to be convinced, even if her mother wasn’t. The jobs are fewer and farther between and the drift into “churnalism” can feel grim at times, but this was uplifting. In a small corner of our city, the future of women’s journalism looked alive and well.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments