Can two clubs from the same town be merged? It might seem logical - but never underestimate intra-city rivalries

THE WEEKEND DOSSIER: History has shown they can also be successful

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference."Stand up if you hate the Gas,” they sang at Ashton Gate on Sunday, and they will again on 22 March. Never mind that Bristol City were playing an FA Cup tie against Premier League opponents last weekend, and will be in a Wembley final in March. Nor that they are heading for the Championship while the Gas (Bristol Rovers are known as “Gasheads” because of the proximity to gasworks of their old Eastville ground) are slumming it in non-league. Rovers may be out of sight in football terms, but they are still on City’s minds.

In Bristol local rivalry runs deep. As it does in Sheffield, Liverpool and Nottingham, English football’s other two-club cities. Which is a mixed blessing. Outside of those, and the major conurbations, English football is a landscape of one-club towns and cities. From Plymouth to Newcastle, Gillingham to Burnley, there is only one team. The exceptions are, arguably, Stoke-on-Trent (with Port Vale in the Six Towns) and Liverpool, and the latter only because Everton fell out with their Anfield landlord in 1892.

London, Birmingham and Manchester are big enough to sustain several clubs, from giants like Arsenal and Manchester United to relative minnows such as AFC Wimbledon and Oldham. The success of Liverpool and Everton suggests Merseyside, with its passion for football, is as well. But are the others?

Take Nottingham. County are founder members of the League, indeed, its oldest club, but have spent four seasons in the top flight since 1926 and last won a major trophy 121 years ago. Forest, remarkably, won two European Cups and the league title under Brian Clough, but have not been in the top flight this century.

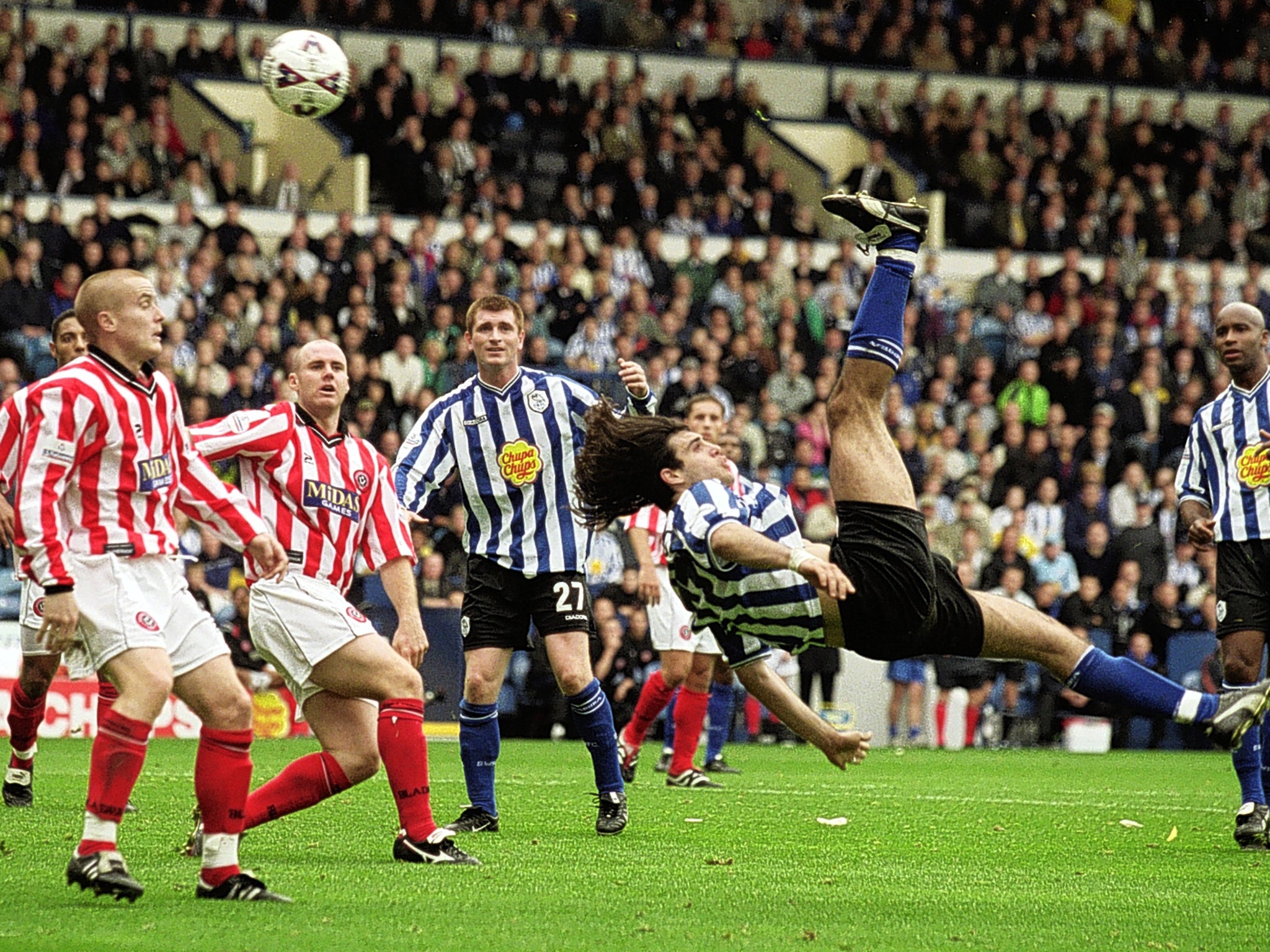

The Sheffield clubs have won 13 major honours, but only Wednesday’s 1991 League Cup within the last 80 years. Since 2000 they have spent one season in the top flight between them, but four each in the third.

The 49,309 who packed Hillsborough on Boxing Day 1979 for the Steel City derby, when both teams were in the old Third Division, shows the depth of rivalry between Wednesdayites and Unitedites, but would not one Sheffield club have achieved more with the whole city, its fans and businesses, behind them? Similarly with Bristol and, in terms of sustained league form, if not European success, Nottingham?

Look at the Scottish Premiership. In third place are Inverness Caledonian Thistle, a club created 21 years ago by a merger of Inverness Thistle and Caledonian, both then in the Highland League.

Leading in Wales are The New Saints, the result of a merger between Llansantffraid (then called Total Network Solutions) and Oswestry Town in 2003. They have since become the dominant club, winning eight League of Wales titles.

Further afield Twente, who were steered to the Dutch title in 2010 by Steve McClaren, were formed by a merger in 1965, Serie A’s Sampdoria by a merger in 1946. The phenomenon is most common in Belgium, usually driven by financial imperatives. Among the more notable Beveren (whose past players included Jean-Marie Pfaff and Yaya Touré) merged with Red Star Waasland in 2010, Antwerp clubs Beerschot and Germinal Ekeren joined in 1999, and Zulte-Waregem was formed by a partnership in 2001. This has been a success, with the new club playing for several seasons in Europe – they beat Wigan last year. But the Germinal-Beerschot union was less propitious. The club subsequently split and folded.

In England, mergers in the professional game are anathema to fans: witness the furore which greeted Robert Maxwell’s attempt to create Thames Valley Royals out of Oxford United and Reading in 1983 and property developer David Bulstrode’s plan to merge Fulham and QPR four years later. Mergers were, though, common in the game’s early years. Newcastle United, for example, were formed out of Newcastle East End and Newcastle West End in 1892 while Rotherham County and Rotherham Town became Rotherham United in 1925.

More recent unions have been in non-league. Two current Conference clubs were created in 2007, Hayes & Yeading and Solihull Moors, while the merger of Rushden Town and Irthlingborough Diamonds in 1992 forged a club that rose from the Southern League’s Midland Division to what is now League One by 2003. However, by 2011 they were back in non-league and wound up.

The one great success, in league terms, has been Dagenham & Redbridge. The League Two club were created by a merger between Ilford and Leytonstone in 1979, adding Walthamstow Avenue in 1988 to make Redbridge Forest, then, in 1992, Dagenham. In 2007 they achieved league status, which has been maintained despite gates averaging less than 2,000.

It might be thought that this success story, drawing on four clubs, would attract larger gates than that but, of course, not all those who supported the old outfits feel part of what they call “the Frankenstein club”.

The old clubs each had proud histories (all more so than Dagenham) with multiple Amateur Cup wins. While Dave Andrews played for Leytonstone in the 1968 Amateur Cup final and later became Dagenham & Redbridge chairman, not everyone felt the lineage survived. Local teacher Joe Durston was first taken to Ilford as a five-year-old, and later watched Dagenham, but said he feels no affinity for the current club. “I know plenty of people who followed Ilford or Leytonstone, but wouldn’t cross the road to watch Dagenham & Redbridge,” he said. “The club as it exists now bears no relation to the old clubs. My father [Danny Durston], who played for Ilford in the 1958 Amateur Cup final at Wembley, hated it with his Ilford connections.”

And this is the nub of the problem. Merged clubs lose fans as well as gain them. If formed way back, “Bristol United” would probably have fared better than either City or Rovers have done independently, but there is too much history and animosity to merge now. The same goes for Sheffield. Instead, fans may as well enjoy the rivalry. Besides, who’s to question that intra-city competition has spurred on Everton and Liverpool, while sole-club status enabled successive owners of Newcastle United to coast?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments