Why are there so few British-born Jewish players in England's top flight?

While Jews are twice as likely as the general public to be devout football fans, there's not been a British-born Jewish player in England's top flight for four decades

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It was the late Liverpool manager Bill Shankly who famously articulated soccer's claim to be an alternative religion with his quip, "Some people believe football is a matter of life and death… I can assure you, it is much, much more important than that."

Rabbi Tony Bayfield admits to pondering the merits of Shankly's theological position when he takes his seat at West Ham's Upton Park ground every other Saturday as a season-ticket holder. "Maybe, I think, Shankly was right," says the president of the Reform movement within British Judaism. "Or at least, he was right in the case of Jews, in that Jewish communal life is a matter of life and death, but for many of us, football is more serious."

Footie in preference to synagogue? Surely that's blasphemy. Rabbi Bayfield laughs off the suggestion. But those on the conservative wing of British Judaism, I point out, would question whether he should even be attending matches on a Shabbat, the traditional day of rest. He is equally unrepentant on that score.

"For me, as a Reform rabbi, football on a Saturday afternoon isn't incompatible with the spirit of Shabbat. To go from being together as a family in the synagogue in the morning to being together as a family at the football in the afternoon [he sits with his son and grandsons] captures for me the idea of Shabbat as delight."

I'm not sure whether that justification would have silenced the opposition fans who, for decades, taunted the large number of Jewish supporters on the Tottenham Hotspur terraces on Saturday afternoons with the chant, "Does your rabbi know you're here?" Rabbi Bayfield, it seems, did and for him it wasn't, nor isn't, an issue.

Nor, indeed, is it for many other Jews, be they Liberal, Reform or Orthodox. A new exhibition at London's Jewish Museum suggests that the 250,000 strong British community, in all its many shades of religious practice (and non-practice), is more prone than the rest of the population to be keen football fans and to attend matches, Shabbat or no Shabbat. It is one of a number of eye-catching statistics turned up by Joanne Rosenthal, curator of Four Four Jew: Football, Fans and Faith.

"That one," she recalls, "came from a public policy paper, published in The Jewish Chronicle in the late 1990s. It showed that Jews were roughly twice as likely to be active football fans than members of the general public." That picture of a disproportionate belief in, and passion for, the beautiful game is reinforced, she adds, by the high numbers of Jews currently involved in the game as players' agents, as football writers or in management of football clubs.

But, like all statistics, those underpinning this exhibition tell several different stories at once. So while Four Four Jew includes displays of memorabilia on notable individual Jewish footballers, including Mark Lazarus (who scored the winning goal for QPR in the 1967 League Cup final at Wembley), Barry Silkman, a Manchester City midfielder in the glory days of Malcolm Allison, and present-day star Dean Furman of Rangers and now Doncaster Rovers, it also highlights the historic dearth of British-born Jewish players in England's top division, which has more recently become a famine. Strikingly, there has never been a Jewish player capped for England at senior level (George Cohen, full-back in the 1966 World Cup-winning team, was of Jewish ancestry, but raised Anglican).

So how to reconcile all these facts into a single picture? Let's start with the absence of Jews on the pitch when there are so many in the stands and directors' boxes. An obvious case of prejudice, perhaps?

"Not true," insists Barry Silkman, who rounded off a distinguished career with Leyton Orient and even a loan spell at Maccabi Tel Aviv in Israel before becoming an agent. "Perhaps when I was 16 and starting out, there was one manager who might have been a bit that way," recalls the 61-year-old, "but aside from that I never once came across any sort of discrimination because I was Jewish." So why does he remain – by his own account – the most recent British-born Jew to play in top-flight football here? "That's a complex one," he says. "And sensitive. I was born in the East End of London and my parents were very poor, but as time has gone on many Jewish families have become more comfortably off. They've moved out of the East End."

But many went to north London, where Arsenal and Tottenham both have large Jewish followings to this day. "Yes, but you see, my parents brought us up to fight, mentally and physically. There were, for example, a lot of Jewish boxers back then fighting for British and European titles, but the physical side doesn't seem to matter so much any more. So playing football is seen as a hobby for their children, something to go and watch, but not a possible career. They're a bit too comfortable for that now."

So it comes down to class – in socio-economic terms, that is, not in the sense that Match of the Day pundits use the word. And it is certainly true that most British-born players who make it today in the Premier League come from working-class homes. With the Jewish community now largely middle-class, it is more likely to produce doctors and lawyers than the next Wayne Rooney.

Rabbi Bayfield, though, has another way of looking at it. "By and large," he says, "Jews have done better when it comes to Nobel Prizes for physics than they have for medals in sport. We have a strong tradition that favours debate and discussion over the physical."

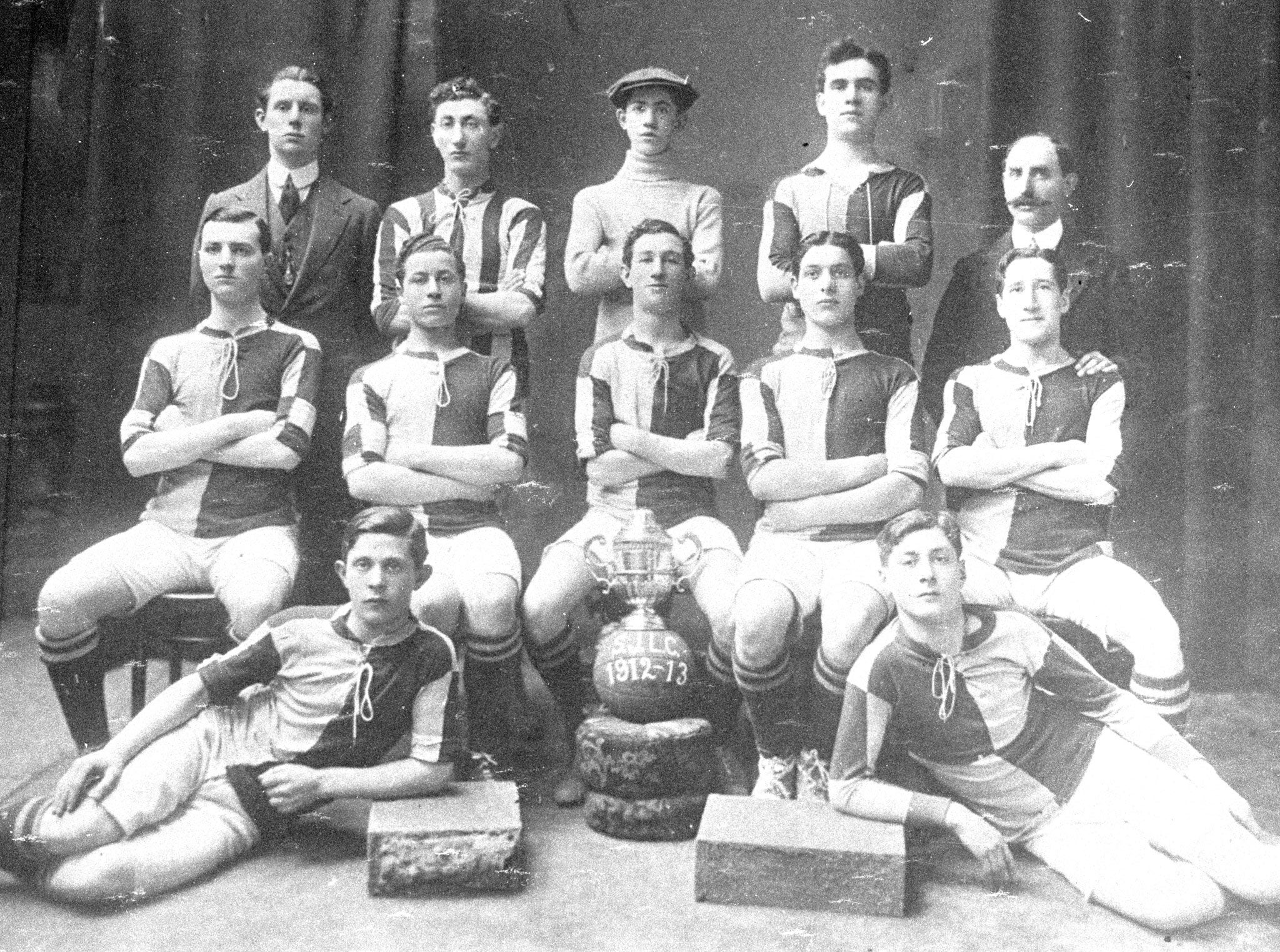

If there was ever mileage in that stereotype of Jewish men as Woody Allen-esque weedy, bookish types, fundamentally unsuited to the rough and tumble of the penalty area, a strong riposte came in the shape of all-Jewish soccer teams who played in secular national leagues. The best-known example was MTK Budapest in Hungary before the Second World War, a self-consciously "Jewish" club that won 13 league titles in two decades. Perhaps it was the memory of their prowess, post-war, that inspired Major Harry Sadow, Frank Davis, George Hyams and Asher Rebak, to establish Wingate FC along similar lines.

There had been an earlier attempt to set up an all-Jewish club at Stratford in east London, to be known as The Judeans and to play in the Football League, but it floundered on the requirement to play on Saturdays. That didn't prove an obstacle for Wingate, based from 1946 in north London. They played first in the Middlesex Senior League and then in 1952 won promotion to the London League and later the Athenian League.

"Wingate was formed," says curator Joanne Rosenthal, "by Jewish ex-servicemen who were alarmed at the resurgence of anti-Semitism after the War. Mosley's Black Shirts had reappeared, but the founders of Wingate wanted to show that there was a better way to fight than fists. And that better way was by being good at the British national sport of football."

Wingate may have included only Jewish players on the team sheet, and a blue-and-white strip that recalled the Star of David and the Israeli flag, but its assimilationist credentials are clear in its choice of name. It was taken not from a Jewish hero but from a much-decorated Gentile, the British General Orde Wingate, a noted supporter of the creation of the state of Israel. "It symbolised," says Rosenthal, "that attitude at Wingate of Jews saying that we play football too, we are English too, we are like the rest of you."

Mark Lazarus – who had decided against following in the footsteps of his older brother Lew into the boxing ring – joined Wingate as a 15-year-old in 1953. He was originally from the East End, but his family had moved out to Essex where he was, he recalls, the only Jewish boy at his school and faced no end of abuse. "What I do remember about joining Wingate was that it was all Jewish," he says, "and since I'd grown up in Romford playing with anyone, that was new to me. But when you're that age, you don't think too much about it. They asked me to play and offered to pay me a few quid as an amateur."

Lazarus's own career took him round various major-league clubs – including three separate spells at QPR and a big-money transfer to Wolves for a club-record fee that made headlines. At the end of his playing days, he returned to Wingate in 1973, but by that time, he remembers, the side included Jews and non-Jews. The process of assimilation had turned another corner.

The Jewish Museum exhibition (part of the FA's 150th anniversary celebrations) also charts that wider story of how football became a vehicle for British Jews to lay down common roots in wider society. Among the items on display is an account of the then-Chief Rabbi visiting the Brady Street club in Stepney in the 1920s and talking enthusiastically about "seeing the ghetto bend being ironed out of [the boys]".

Rather less paternalist and more current is the short film The Worst Jewish Football Team in the World, which follows the fortunes of Broughton "B" FC, a boys' team playing in Jewish leagues in Manchester in the late 1990s that was regularly on the wrong end of 27-0 scorelines. Many of the players come from ultra-Orthodox homes where notions of integration are rejected. "So they probably won't go to the cinema or listen to secular music, but football is acceptable," says Rosenthal. "It has that ability to break down barriers. They are doing what all boys do, regardless of religion, and even though they are only playing against other Jewish boys, their opponents come from more Liberal homes. So there is still that element of assimilation."

That desire in the first half of the 20th century to use football to become part of the crowd was sometimes stated explicitly, other times not. "My mum went up the Spurs every week," recalls Silkman, "and she always stood where everyone around her was Jewish, so she wouldn't have known what you meant by integration." But it is one of the factors, Rosenthal argues, that lies behind the current high levels of Jews among football supporters and administrators. That and their presence in the professions, and their preference for urban areas, where there is likely to be a club on their doorsteps.

Film producer Marc Samuelson, London-based but a devout Manchester United fan, believes there is another factor that explains the disproportionate number of Jews involved in running football clubs. "Part of that same process of integration was for Jews to get involved in businesses that weren't dominated by the upper classes, and the ownership of football clubs was one of those – rather like the film industry. They were both open to incomers, with no artificial barriers or prejudices."

But Samuelson sees no strong link today between his own religious identity and his enthusiasm for football. "It may have existed in the past, even been encouraged in the past as a way of fitting in, but it is certainly not a conscious thing any more for Jews of my generation."

Rabbi Bayfield begs to differ. He continues to spot a discernible connection between the two. "For many Jews, going to Spurs, Arsenal, Manchester City, Leeds or, in my case, because I like lost causes, West Ham, I still think there is something distinctive about sitting and talking with your friends as you watch the match. It is that aspect of doing what everyone else is doing, even when you come out of a Jewish community that still has so much about it that is structured to preserve its own integrity. Going to football with everyone else feels like a great relief."

Four Four Jew: Football, Fans and Faith opens at the Jewish Museum, London NW1, on 10 October (jewishmuseum.org.uk)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments