The Wembley sale debate misses the point – the grassroots crisis is symptomatic of today’s broken society

We’re not just talking about football’s skewed financial model here, writes Jonathan Liew, but that of the country as a whole: the relationship between the public sphere and private enterprise, between capital and the consumer, between a society and its citizens

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.What was going to happen when the money ran out? That was the question the advocates of selling Wembley Stadium never quite managed to answer. Once Shahid Khan’s £600m had been skimmed, parcelled off and disbursed around the country, presumably the need to maintain facilities, continue existing programmes and pay staff wasn’t going to disappear overnight. So where was the Football Association going to find its next windfall? Selling off the England right-back position? Turning St George’s Park into a petting zoo? Raffling Phil Neville?

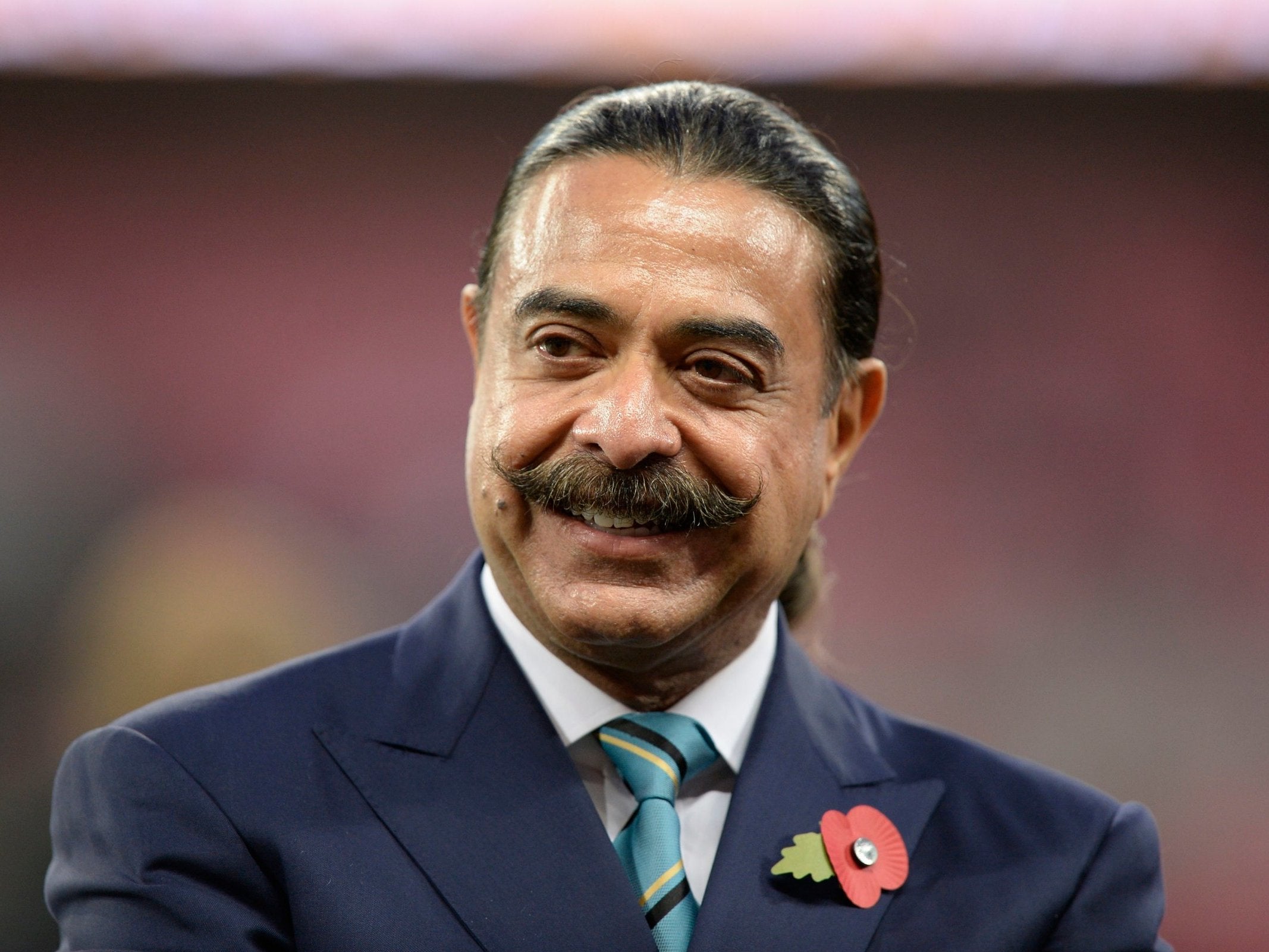

Of course, in one sense this is all academic now that Khan, the owner of Fulham and the Jacksonville Jaguars, has stepped away from the sale in order to spend more time with his moustache. And yet on another level, the fury in some quarters at the loss of money that was never the FA’s to spend in the first place, and the withdrawal of an offer that was only ever theoretical, betrays English football’s curious and self-defeating taste for melodrama, its blindness to the bigger picture in favour of short-term solutions that may as well be borrowed from an ITV1 game show.

If this whole affair has achieved anything at all, then it is to draw a little fleeting, belated attention to the abject state of grassroots football in this country, even if the pitch of the debate has occasionally veered into the surreal. “A tear rolls slowly down the cheek of a child staring at a pitch waterlogged again,” begins one particularly demented take in a respected broadsheet newspaper, blaming the FA’s “blazers” for refusing to sanction the sale, betraying the nation’s children and very possibly – most of it was behind the paywall, unfortunately – kidnapping their parents.

Of course, it wasn’t just the blazers opposed to the Khan deal. A Football Supporters Federation poll found that only one in three fans were in favour of selling Wembley, while the FA’s own research showed that only 38 per cent of grassroots footballers – the direct beneficiaries of any revenue – thought it was a good idea. The rest, like many of us, could spot a gimmick when they saw one, the unmistakable whiff of a long-term asset being flogged for short-term gratification.

We should point out, at this stage, that there is no real prestige argument to be made here. Opposition to the sale of Wembley Stadium need not be based in tradition or pointless nostalgia, and indeed one might surmise that if the pride of English football is so fragile that it can be irrevocably dented by selling off the site of the Carabao Cup Final, then perhaps it wasn’t worth very much to begin with.

No, this is really about business, and more specifically football’s unique and windswept position in the blisteringly ruthless economic microclimate that is the public sector in 2018. And it’s hard not to feel in some important sense that the giddy, premature and subsequently punctured excitement over the Wembley windfall is emblematic of a system broken from middle to bottom (the top, of course, is doing peachily). We’re not just talking about football’s financial model here, but that of the country as a whole: the relationship between the public sphere and private enterprise, between capital and the consumer, between a society and its citizens.

How did we reach a point where Premier League clubs are generating nine-figure revenues and average footballers are changing hands for £25m while the vast majority of facilities in this country are scarcely fit for purpose? It happened when we became intensely relaxed about billionaires hoovering up public assets while squirrelling away their fortunes in offshore bank accounts. It happened when we stopped seeing sport as something that makes people healthy or happy, but as something you charge people for.

It happened when we tolerated the ideological cuts carried out to local government by successive Conservative-led administrations, cuts that have had a traumatic effect on grassroots sport and plenty else besides. It happened when politicians convinced us that wealth at the top would ultimately enrich us all, that the only way of ensuring the provision of vital services was to privatise, sell, pare the public sector down until it had nothing more to offer. And so to pin all this on Mino Raiola, or Richard Scudamore, or the blazers at the FA, or Richarlison, rather misses the point. They weren’t the cause, just some of its many, many symptoms.

The Premier League would argue, of course, that they and their clubs generate £3.3bn in tax revenues a year, support 100,000 jobs, add £7.6bn in value to the economy. And even if you don’t quite buy all that – and HMRC has been taking a much greater interest in football’s opaque apparatus of player transfers, offshore banking arrangements and image rights over recent years – it doesn’t change the fundamental fact of the matter, which is that over the last two decades, those with money have developed ever more intricate strategies to both keep and multiply it.

Of course, there are things you could try in the meantime. A levy on agents’ fees, an idea advocated by Gary Neville in a desperate attempt to save his brother from the indignity of a forced raffle, would likely drive up transfer fees and ticket prices still higher, and would be pointless unless it also applied to intermediaries based abroad. A global Tobin-style tax on financial transactions – a levy on every transfer, or perhaps a portion of any transfer fee – would restrict freedom of movement, and disproportionately penalise smaller clubs who rely on a fluid transfer market in an unstable marketplace. And besides, it would require a certain faith in Fifa to collect and distribute the money honestly and equitably, which is asking rather a lot from an organisation you wouldn’t lend your biro.

In short, then, there are no real quick fixes here, regardless of anything you may be told by well-meaning columnists or men with strange moustaches. If you want to fix the financial model of grassroots football, you need to fix the financial model of football, which means you need to fix the financial model of society, which means you need to get big multinationals to pay their taxes and give people a genuine stake in their community.

You need a shift in the culture of grassroots sport, which means you need a shift in the culture of local government, which means you need a shift in the culture of our entire political class, and the idea that sport is a public good that should be free for all, rather than a private enterprise to be exploited. You would, in short, need to sweep away virtually the entire intellectual basis of our capitalist society, which – to put it mildly – is no picnic. Small wonder, in retrospect, that many would rather just take the money and run.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments