How football failed Nobby Stiles, the Manchester United and England icon struggling with dementia

The sport's authorities and Stiles' former club have done precious little to help 'Nobby', whose struggles with Alzheimer’s and dementia are thought to be linked to the game he loves

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Nobby Stiles was the man Bobby Charlton described as the forerunner of Roy Keane – a “dog of war” who could be depended upon to shut down danger wherever it materialised on a football pitch. So it is perhaps not surprising that he has faced his toughest fight with resolve and no little humour.

Stiles has been doing battle with Alzheimer’s and vascular dementia for 15 years, to the extent that his mind has now become terribly frayed, but at one point amid the struggle to recall who he’d spoken to just five minutes earlier, he grinned at his son, Rob. “I make new friends every day,” he told him.

The 74-year-old’s powers of speech have gone and his decline has been so steep in recent weeks that visiting him is out of the question for all but the close family. For them, the sorrow is multiplied by a sense that the mainstay of England’s World Cup triumph and Manchester United’s 1968 European Cup has not been afforded the thought and care he might have done by his beloved game, amid the struggle of his fading years. Most of all, the family thought that football – and particularly the Professional Footballers’ Association - would have shown a commitment within Stiles’ lifetime to complete research on the link between heading a football and degenerative brain disease. Definitive research has not even started.

Stiles was not one to demand such endeavours on his behalf. The wing half back might have been a giant at the heart of the United and England engine but he was a shy man, too. Hundreds flocked to hear his after dinner speeches when his playing days were done, but he was not a comic turn. “He didn’t try to be what he wasn’t,” says his son, Rob.

He needed that extra income when the idea was put to him, because football alone did not furnish him with a comfortable retirement. The game gave him a decent living when he played, as he was part of the generation which campaigned for an end to the maximum wage. But he was not one of United’s top earners and certainly not set up for life. His initial £3.25 a week United wage had risen to £20,000 a year at Middlesbrough, when he left Old Trafford for the club in 1971.

He earned less than that when, at Brian Kidd’s suggestion, Sir Alex Ferguson brought him back to United in 1989 to coach the young players. The Stiles’ still needed the income his wife, Kay, brought in from her job selling Waterford crystal at Kendals department store in Manchester. He’d been a national hero but still had to scuttle around to make a living when his playing days were done.

As United soared, Stiles began to decline. He left the coaching role in 1993, suffered a heart attack in 2002 and it was a year later, at the age of 61, that he first seemed to be altered and confused. In retrospect, the family now know that this was the first sign of dementia but neither they, nor he, wanted to admit it. “He was always so fit, never carried weight, always had low blood pressure and perhaps that was why we assumed it was nothing. We wanted it to be nothing,” says his son. The odds of a diagnosis between the ages of 40 and 65 are one in 1,400.

In 2010, aged 68, he suffered a transient ischemic attack (TIA), or ‘mini stroke’ which left his family in no doubt that there was a serious problem. It meant that Stiles stopped driving and though he tried to maintain the after-dinner speaking - his sole source of income - his eldest son, John, had to work alongside with him, guiding him through the questions and stories.

It was at that time that Stiles decided to sell his medals. “I have had a bit of bad time and I want to leave something for my family,” he said in September 2010. “These things are very, very special to me: the memories of me growing up as a kid and of my football career.”

He was diagnosed with prostate cancer in 2013 and while at Manchester’s Christie Hospital suffered another stroke which left him confused. “He wasn’t our dad,” says Rob Stiles. He spent periods of time in two other hospitals, suffered two bad falls, one of which left him with a broken pelvis. The once bright and optimistic Stiles retreated within himself and was at times overwhelmed by anxiety. The sons made his condition public in 2015, asking for privacy as they tried to help their mother.

One of the very few other times we remember them getting in touch was when they wanted dad to do a dinner for them for free

Football’s mixed response to all of this has been revealing. Stiles’ old England teammates, who already knew, were the most concerned. As always, Sir Bobby Charlton remained a regular visitor to the Stiles’ modest semi-detached house on Kings Road in Stretford. He has been close to him ever since the two of them, Shay Brennan and David Herd ironically called themselves the Big Four in their United days.

Stiles had his good and bad days and Charlton happened to pay a visit on one of the latter. It was distressing. “People don’t know how to react,” says Rob Stiles. “Dad knew that and in time he couldn’t bring himself to see people.”

If they’re honest, the family would say they were disappointed that they have felt virtually no communication has been forthcoming from United since Stiles left the club, 14 years ago. He has always considered it an honour to have run out in the club’s colours, so didn’t flinch when he asked about getting tickets for the team’s home match with Liverpool in 2009. He was told he must pay full price. He’d wanted to accompany his granddaughter, Caitlin, to her first Old Trafford match, on her birthday.

In such circumstances, a rare piece of correspondence from those of the modern United generation of players meant a lot. It was a card from Wayne Rooney, written out by the player after the family had disclosed his plight to say how he had enjoyed watching footage of Stiles and, how sorry he was to hear he was struggling.

Manchester United say that Stiles had been invited to the renaming of a stand after Sir Bobby Charlton last April, that many ex-players attended on match days - some in the director’s lounge, and that Stiles would always be welcome at Old Trafford. They cite their £200,000 purchase of his World Cup and European Cup winners’ medals in 2010 – which are in the club museum – as well as support for his dinner speeches. The club say they wanted to respect his family’s wishes for space and privacy when his health deteriorated.

His illness had progressed too far for him to attend any stand re-naming, or even a similar ceremony in his own honour shortly afterwards, from which he would have derived incalculable pleasure.

It was the re-naming of the street next to the school he attended – St Patrick’s Primary in his Collyhurst – as Nobby Stiles Drive. Stiles’ lifelong primary school friends Danny Cooney and Tony Kennedy – rather than anyone in football - had decided they would see to it that the individual they have always called by the full ‘Norbert’ should have a street in his name. They pursued the idea with Manchester City Council and the city’s Lord Mayor, Paul Murphy. Until recently, Cooney and Kennedy still drop in to see him every week.

United asked if they could attend the ceremony, to film and do interviews, though Stiles’ wife was disinclined to grant the request. “One of the very few other times we remember them getting in touch was when they wanted dad to do a dinner for them for free,” says Rob Stiles.

Stiles has been too ill to share with his family the beginnings of club’s recovery under Jose Mourinho, though he would have enjoyed it. “He somehow always knew when things were looking up,” says Rob Stiles. “We watched the 1999 European Cup final together at home and I was gloomy. He told me: ‘We’re going to win it. You watch it.’ He loved the club and the game.”

The 50th anniversary of the 1966 World Cup triumph coincided with the first contact the family can remember in years from the Football Association, who last month wrote to Kay Stiles to say that they had become aware a number of Sir Alf Ramsey’s team were not so well and that they wanted to do what they could. The governing body followed this up a phone call in which Mrs Stiles was told that there was a means tested scheme, with an application form if she wanted to fill it in and apply for money. She declined.

But it is the lack of progress on the link between football and degenerative brain disease which frustrates the family. The FA and PFA first promised a joint study in 2002 when the former West Bromwich Albion player Jeff Astle's inquest confirmed that his death was caused by heading the old leather footballs. Nothing has been forthcoming.

We watched the 1999 European Cup final together at home and I was gloomy. He told me: ‘We’re going to win it. You watch it.’

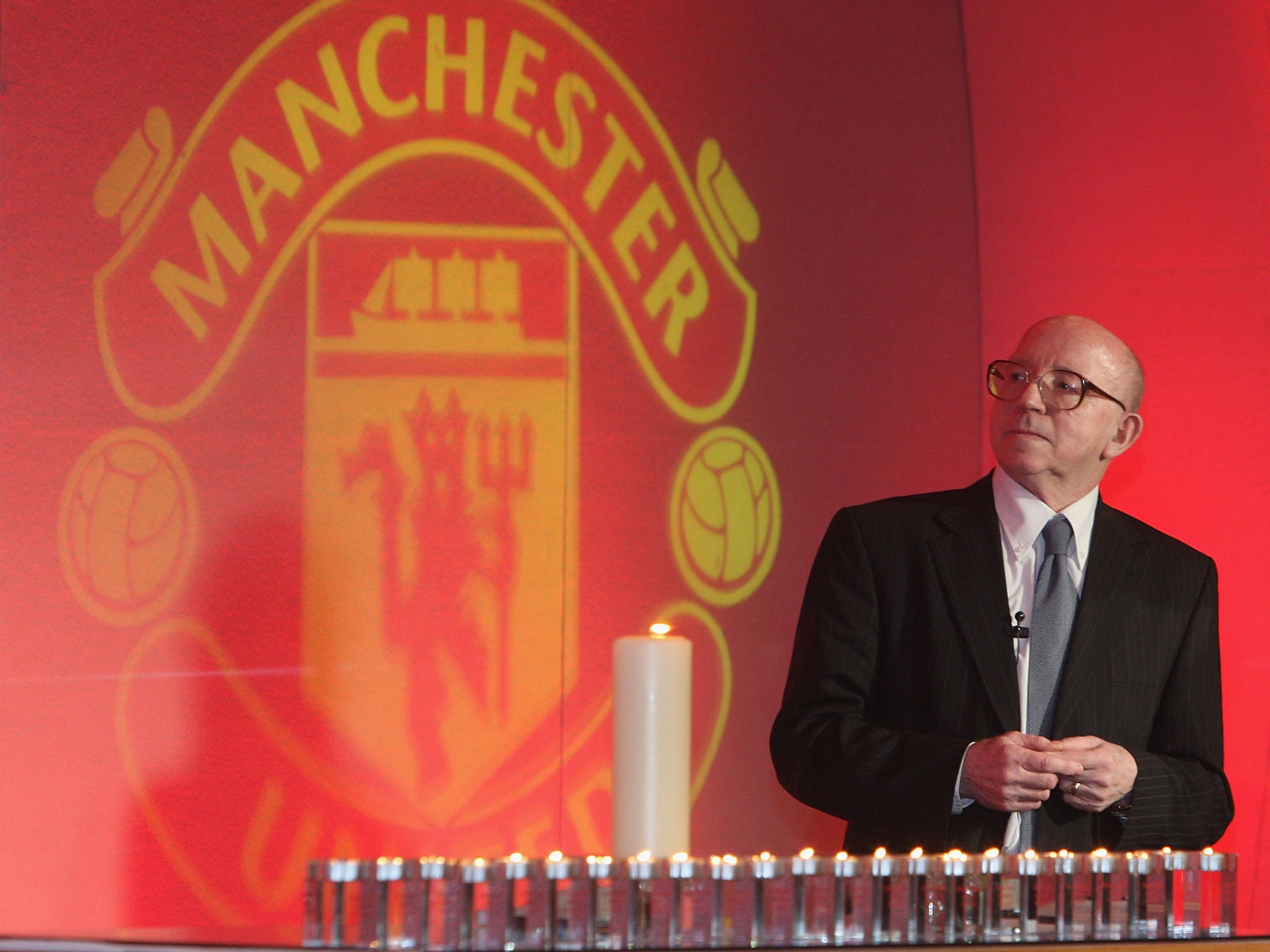

PFA chief executive Gordon Taylor told The Independent on Tuesday that a “medical committee” comprising the PFA, FA and others had been constituted to look at the issue, with work yet to get under way.

Taylor said the FA had approached the union last year to ask if they could help any members of the 1966 team who were struggling and that he had told them to be sensitive. “Nobby would have been written to like all the other members of the 1966 squad,” Taylor said. “But it needs to be treated very delicately. I told the FA: ‘Don’t frighten people off with a standard form. Don’t make it look like an income tax form has come through the letter box. It virtually needs a meeting, face to face.” Taylor said he had personally told the Stiles family “come on and ask if we can help.” The FA said: “We were looking to celebrate or mark the 50th anniversary of ‘66. Our contact with Nobby was part of the engagement.”

Stiles was too ill to read letters. “Dad’s illness hadn’t even become obvious to us when the first promise of action came from the FA and PFA to look at the possible link,” says Rob Stiles. “We are talking about the possibility that this is the football equivalent of industrial disease. So many in the game seem to have been affected in the same way. The pleasure that dad brought to so many doesn’t seem to count for anything now.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments