Back to the banlieues: Drogba's journey home

Paul Newman joins the prolific striker as he travels to his first club – and encounters the thoughtful side to an explosive character

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Didier Drogba looked around him. The surroundings were familiar – the blocks of flats towering over the pitch, the swarms of children enjoying their sport and the background hum of the nearby Boulevard Périphérique – but this was not quite how he remembered the Stade Louison Bobet.

The pitch had been relaid with synthetic turf and there were new indoor tennis courts, a gleaming athletics track and smart clubhouse.

The Chelsea striker was back at Levallois Sporting Club, the amateur side in the Parisian suburbs where he played for four years as a teenager, for the official renaming of the arena – as the Stade Didier Drogba. The Ivory Coast international is a major reason why they have such facilities: Levallois are paid a percentage of all his transfer fees and received a cheque for more than £600,000 from Chelsea following his arrival from Marseilles six years ago.

In an age when some players are as likely to make the news in a nightclub as at a football club, Drogba's visit was a reminder that other footballers have different priorities. "I do go out as well and party, but things like this are more important than going out and partying," Drogba said. "To give a message to kids, to tell them that I started here, and I made it – and am now playing for Chelsea."

He added: "I love what I'm doing and I'm really grateful to God and to all the people who helped me to achieve what I did. You see all my ex-managers here, some ex-players I played with. It's nice to see them. It's a simple thing and I love that."

If any footballer has earned his millions it is the 32-year-old from Abidjan. Sent by his parents to France at five to live with his uncle in the hope that he would benefit from an education they could not provide, Drogba was 24 before he made his first big-money move, from Guingamp to Marseilles.

Until that point much of his life had been spent trailing around some of French football's more obscure outposts. Drogba's uncle, Michel Goba, who was in the crowd here to see his nephew honoured, played in the French Second Division for Brest, Angoulême, Dunkerque, Besançon and Abbeville .

"Football wasn't the reason he came to live with my wife and I – it was to go to school," Goba recalled. "He was a good pupil. He used to finish near the top in his class.

"When it came to football at first he was just like any other kid. It was really only when he was about 12 or so that you noticed he had real football ability, although you could see before that he had this desire to make it as a footballer.

"When he was eight or nine he would come back from school and I would ask him: 'What did you do today?' He would reply: 'I played football'. I would say: 'That's not going to help you when you grow up. Football's not the job for you'. But he would insist: 'That's what I want to do'."

Goba, now 49, was also instrumental in his nephew's conversion from right-back to centre-forward. "What are you doing stuck back there?" he once told him. "Get up front. In football, people only look at the strikers."

Drogba did not see his parents for three years, but they joined him in France when he was 13. Two years later the family moved to Levallois-Perret and it was at the local football club that Drogba started to make a name for himself. A number of recent France internationals have emerged from the more infamous Parisian banlieues, but Levallois-Perret, just north of the Périphérique, is not a quartier difficile like Les Ulis or Trappes, where Thierry Henry and Nicolas Anelka grew up. There are chic clothes shops and trendy Japanese restaurants and not far from the stadium, wedged between luxury apartment blocks, is the Parc Gustave Eiffel, a delightful public garden bursting with lush plants.

Like nearly all the French capital's suburbs, however, Levallois-Perret has excellent municipal sports facilities and Drogba thrived under the wing of the club's technical director, Srebenko Repcic, a former Yugoslav international who is now in his 21st season there.

"Didier played in the Under-17 team, but I got him in the senior side because I thought that would be good experience," Repcic recalled. "Mentally he was very strong and he was a hard worker. There were things in his game that we looked at and he worked very hard at them. What impressed me most was when he moved to another district, at Antony. It meant he had to get the RER train here every time. After some training sessions he wouldn't get home till very late at night."

Playing at a club where he feels wanted is clearly important to Drogba, who received a wonderful ovation from Marseilles' supporters at Tuesday night's Champions League fixture at Stamford Bridge. When he left Levallois he went to Le Mans – where he spent more than four years before enjoying his first taste of First Division football at equally unfashionable Guingamp – despite an approach from Paris St-Germain.

Does Drogba think that having been at such clubs has helped to make him the player he is today? "I think so. You get some values at amateur teams that sometimes in pro football are lost. It's difficult to find them. People are more selfish, more individualist. In an amateur team you share things, you travel together because there is not enough money.

"When I was transferred from Marseilles to Chelsea, and I heard that Levallois had a percentage of the transfer money, which helped the club to survive, I was really happy. It was fantastic. You see all the people here, what they've built on the site, like the tennis courts. It's amazing. Instead of being on the street and doing bad things, the kids can come here, practise, then go back home."

Drogba has not always endeared himself to the public with his on-field behaviour, such as his haranguing of the referee after last year's Champions League defeat to Barcelona and past allegations of diving, but there is arguably no greater philanthropist among the world's great players.

The Didier Drogba Foundation supports health and education in Africa – a charity ball in London last year raised over £500,000 towards a hospital in Abidjan – and benefits from the proceeds from all his commercial deals and the profits from his autobiography and official DVD. He has been involved in a number of campaigns, including one against poverty through his work as a United Nations "goodwill ambassador".

Drogba was even credited with halting civil war in his home country. Within minutes of leading the Ivory Coast to qualification for the 2006 World Cup, Drogba grabbed a microphone in the team dressing room, fell to his knees and appealed live on national television to both sides to lay down their arms. Within days the fighting had stopped.

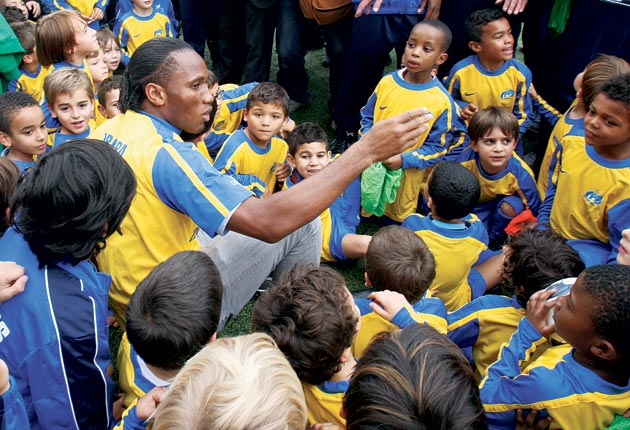

At Levallois the great and the good were queuing up to pay homage. Rama Yade, France's flamboyant Secretary of State for Sport, walked out to greet him on the pitch at the end of a short exhibition match in which Drogba played alongside some of the club's youngest members, while Patrick Balkany, the mayor of Levallois, spoke of the example the Ivorian sets.

"He's a young person who lived here and went on to achieve great success," Balkany said. "He's a great example in the way that he learned here and carried on learning at his next clubs before he made his big moves in football. He's someone who's never been big-headed and has always retained his humility."

The former Marseilles president, Pape Diouf, who took Drogba to the Stade Vélodrome seven years ago, agreed. "Football is a very greedy environment and it's refreshing there are people like Didier who remember where they come from and their friends from those days," he said.

Drogba clearly felt at home. "These people have known me for years and I think I have stayed the same," he said. "You don't change just because you sign for Chelsea or a big team. This is only for a moment, so you have to stay who you are, because there is a life after football."

There were Chelsea shirts all around the stadium, many with Drogba's name on the back. Zadri Ladry, nine, was wearing one but had to wait for a glimpse of his hero outside the gates, alongside all the locals without a pass. "I live here but I support Chelsea and the Ivory Coast," he said. "He's the best player in the world – and he used to live here."

Drogba, who was patience personified as he was mobbed throughout his visit, described it as "a great moment in my life, and not only in my life as a footballer". He added: "From now on the children here are going to say: 'I'm going to play at the Stade Didier Drogba'. That's enormous."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments