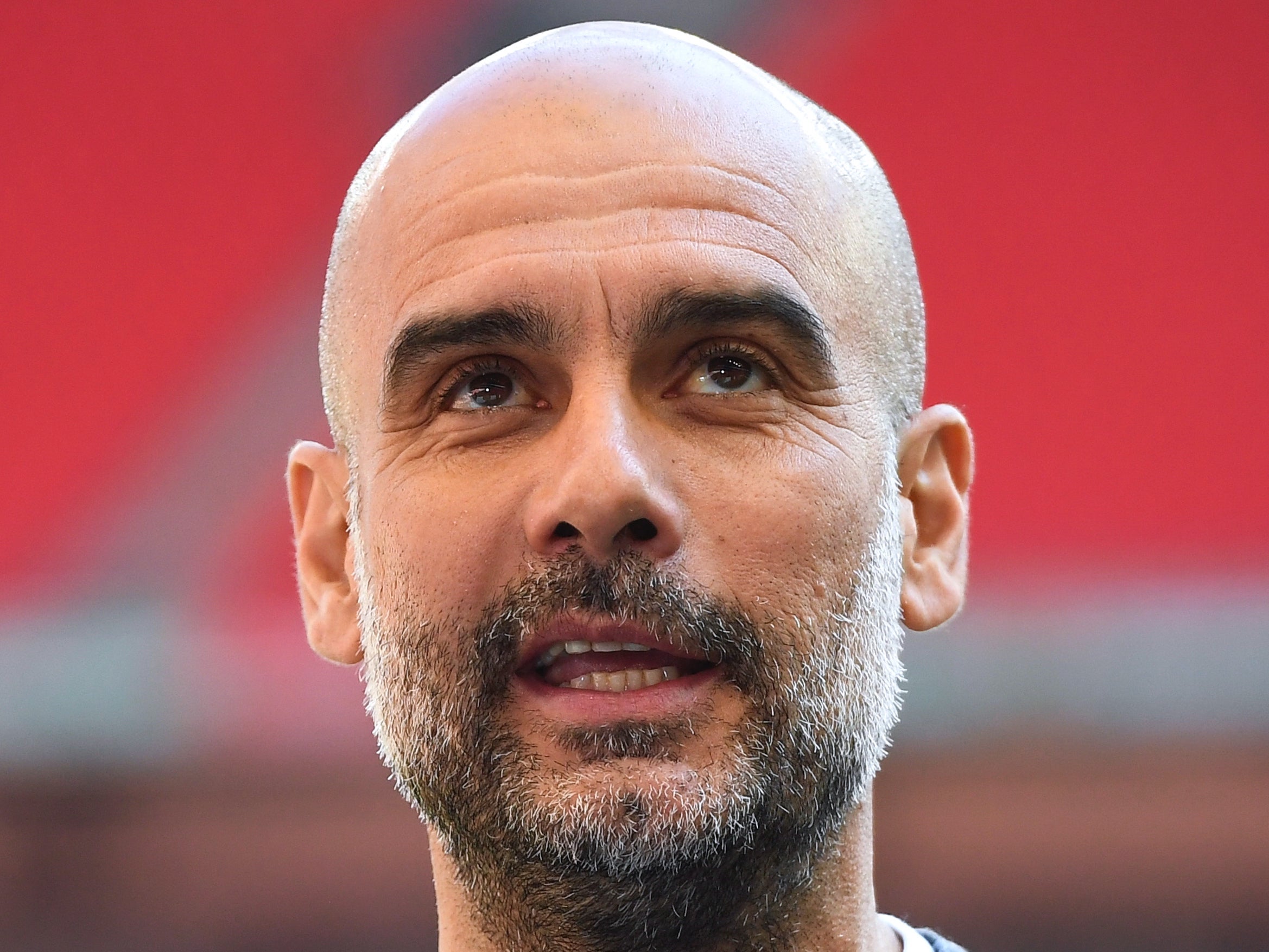

How Pep Guardiola’s own evolution took Manchester City to the Premier League title

The genius behind Manchester City’s success has lifted himself to new heights as his team again showed they are the best English football has to offer, writes Miguel Delaney

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.For some celebrating at Manchester City with Pep Guardiola, it must be impossible not to think of moments this season that weren’t quite so happy.

There was uncertainty, doubt and - occasionally - a fair bit of gloom. Crucially, however, there weren’t the usual histrionics from the Catalan. Many around Eastlands feel that may have been key to securing the third Premier League of Guardiola’s titles in his five years at City, the seventh in the club’s history, and the ninth domestic title of the 50-year-old’s career.

He is now the manager with the second-highest number of medals from Europe’s five major leagues, having overtaken Giovanni Trapattoni’s eight, to go just behind Sir Alex Ferguson’s 13. Only eight managers in the history of the game have won more domestic titles, and four of those are from Scotland’s Old Firm.

City are meanwhile the joint-fifth most successful club in the annals of the English league, having gone level with Aston Villa. That puts something of a historical context on their current wealth, emphasising the extent of the Abu Dhabi transformation. If a state's riches make success someway inevitable, though, that didn’t feel the case for much of this campaign.

There were various points between October and January, however, when many felt this title was impossible. Some of those were the City players.

It is all the more remarkable to think it now, but there was a sense around the club that Guardiola’s time was up. The squad just looked burned out by his intensity. The blunt reality was that a core of players were exhausted by it. That tends to be the cost of modern managerial genius. The expectation was that Guardiola would depart at the end of the season, with one source even saying “a good campaign would be Pep leaving and things not collapsing”.

When Guardiola finally signed that new contract in November, some were even describing it as a “rare mistake” by both him and the club. That feeling grew more pronounced as City made more mistakes in the next few games, both in that unreliable defence and profligate attack. The nadir seemed to be that 1-1 draw at home to West Brom, which was the same week defending champions Liverpool beat Tottenham Hotspur 2-1 with a last-minute winner and then put in a statement performance demolishing Crystal Palace 7-0.

Things seemed to only be going in one direction, and the title only seemed to be going to one place. That was actually when it all changed. Many cite a change in Guardiola.

As a coach who is more histrionic than almost any other, his sideline behaviour is almost the perfect barometer of the true state of his team. Guardiola was described by many around the club as “brooding” during that 1-1 draw with West Brom, but it wasn’t quite that. He was as contemplative as he was concerned, weighing things up. Guardiola had by then already decided to make considerable changes to his tactics, to go with those made to City’s conditioning.

It was why - against most expectations - he was relatively relaxed about City’s poor form when others were rancorous. The backroom staff had already greatly altered the team’s physical approach, in order to adapt to this most hectic ever of football seasons, so that they would have much more energy for the crucial end of the season. The effects of that - as they chase a treble - can now be clearly seen.

There was an awareness that City might be sluggish in those first few months, but that it would be for the better in the long run. Guardiola complemented this by altering the approach of the team, so there was much more calculation to their pressing and movement. It was a more reserved game for a more frenetic time.

Managers with most domestic title wins

Bill Struth 18

Willie Maley 16

Sir Alex Ferguson 16

Valeriy Lobanovskiy 13

Luis Cubilla 11

Jock Stein 10

Giovanni Trapattoni 10

William Wilton 10

Guardiola, in essence, had “figured out pandemic football” before anyone else.

None of this should really be a surprise. He is, after all, a football genius. City are also England’s wealthiest club.

There’s no getting away from the fact that this strangest and most unfamiliar of seasons has ended with the most predictable of winners. That point should be front and centre after all the debate about the Super League. Many of the structural problems that led to football becoming “broken” are as bad as ever. Financial disparity was already ruinous, but has been made worse by state takeovers. Officials at other clubs have complained that there’s nothing now to stop City winning every title for a decade, much like what has happened in Italy or Germany.

The most basic of truths still apply. A period that has stretched every club to their absolute limits - both in terms of energy and finances - has been best navigated by a state project with the most resources. What a shock. It is actually a little disheartening that not even this season, of all seasons, could sufficiently distort the usual realities to make things more exciting.

It even goes back to before that uncertain start. In a year when almost every club had their budgets slashed, City were able to spend over £100m on two defenders.

With one, Nathan Ake, they have been completely unaffected by the fact he has only played eight games. Few clubs would have this luxury with a £40m signing. Even fewer clubs have a player like the other, Ruben Dias.

If the absence of Ake has left City unaffected, the presence of Dias has been transformative. He has probably been the most influential Premier League signing since Virgil van Dijk, having had a similar effect. There is an important historical point there about the rarity of top centre-halves, and another change to Guardiola’s football.

The Catalan has recently been fixated on the issue of City’s expenditure on players, often sardonically bringing it up in press conferences when asked about something else. It is as if he feels reference to it detracts from recognition of his coaching, or the effort of his players.

That is to miss the point.

Guardiola is part of that expenditure. He is one of the best-paid coaches in the world, and gets to manage the wealthiest clubs, for a reason. City have just paid for his genius, too.

And he has more than shown that genius, even beyond the alterations to this team this season. There has been something grander about it, and an element reminiscent of Ferguson.

The Manchester United great had a relatively similar financial advantage over much of the league, even if it was not from a state project, but he maximised it through his relentlessness. Ferguson didn’t just win title after title at the same club. He created era after era, having built team after team.

That is a challenge beyond some of the best in the game. Brian Clough couldn’t manage it. Jose Mourinho couldn’t manage it in the same spell.

It seemed like Guardiola couldn’t manage it, as he’d never gone more than four seasons at one club, and we were seeing familiar issues in this fifth season due to that famous intensity.

The Catalan has instead joined a select group in immediately building a second great team, following Ferguson, Sir Matt Busby, Arsene Wenger, Bob Paisley and Bill Shankly.

It is not just that totems like Vincent Kompany, David Silva and Sergio Aguero have been succeeded by Dias, Phil Foden and Ilkay Gundogan to form a different core.

It is that they also reflect a new playing style. Although figures like Kevin De Bruyne, Kyle Walker and Ederson form similar standard-bearing roles to Paul Scholes and Gary Neville, it is very identifiably a different team cycle.

That reflects Guardiola’s own tactical evolution, which is another resonant theme from this campaign. Dias personifies a much more solid defensive structure. He is not pinning a front-loaded attacking team together, in the way Kompany did. He is leading from the back, in a side that feels like it has a much more substantial foundation. That may potentially point to an evolution in the defensive side in the game, after a period where all the advances have been made in attack.

There has been a significant change in that area too. City are the first English champions to play without a recognised centre-forward, but it is indicative of Guardiola’s influence that isn’t even a point of debate any more. It just illustrates his ability to adapt, and create a team that can kill you in an instant without having a ‘killer’ of a goalscorer.

At the time of securing the title, City’s top scorer in the league is Gundogan, with 12 goals. That is the lowest for a champion in Premier League history, and he is one of only two City players with 10 or more. They do have five players on seven goals or more, which is the most in Premier League history other than the six from - yes - City 2018-19, City 2017-18 and City 2013-14.

Guardiola's range of attackers is emphasised by the fact Raheem Sterling is now a mere stand-in, and not a guaranteed starter.

The manager has simply improvised, and impressively innovated. Necessity has been the mother of a different type of invention.

As to whether it means much more for the future of the team or the game, that doesn’t feel all that likely. City plan to go out and build on this win by signing the striker they’ve been missing - maybe Erling Haaland or Harry Kane, to go with Jack Grealish. It is a frightening prospect - akin to when United went for Alan Shearer - and precisely why those other club officials were so concerned.

Guardiola won’t have that same necessity. Next season won’t have the same rigours. There will be a hangover from this campaign, of course, but it will be something closer to normal - as symbolised by the return of fans.

Guardiola may even return to many of his idealised tactical principles, and something more familiar, by the time supporters come back. The only pity for the club in all this is that fans didn’t get to watch more history being made.

Guardiola instead made do.

A state's wealth helps. His genius maximises it. It leaves everyone else in the English game worried, as Guardiola smiles on.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments