Twenty years on from Kosovo's darkest hour, football is offering a bright new future

Long read: On 5 March 1998 the Yugoslav army launched an attack which changed the country forever. Two decades on, the country and its favourite sport has never felt more alive

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.As the wind sweeps in south from the Klina freeway and the daylight cedes to dusk, the sleepy northern-Kosovan town of Skenderaj could be a thousand miles from anywhere. Spring has started. The cold, though, is perishing.

Dust kicks up off the road where the route in and out of town veers off to join a tarmacked forecourt from where the last bus service of the day has just departed for the capital. Two children kick a well-worn football up against the wall of the bus station, its leather panels flapping as it bounces back off the corrugated steel, the stitching long since having been eaten away by months, perhaps years of play on the dirty concrete.

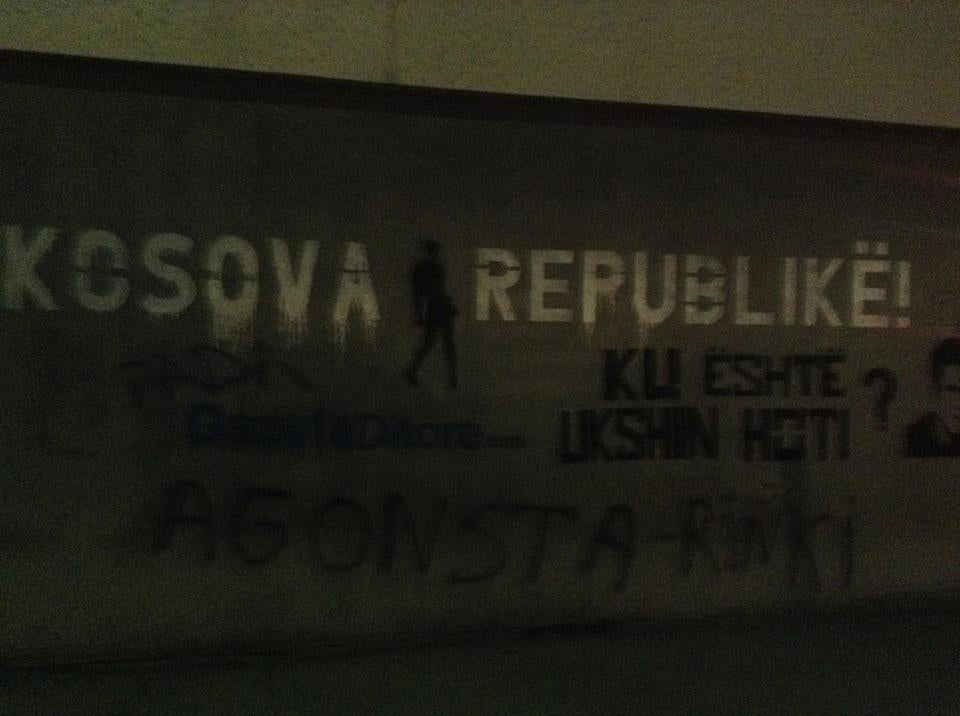

Ditched at the edge of a sprawling mass of rural nothingness, Skenderaj seems almost frozen in time. There is little left now that hints at the horror that occured here exactly 20 years ago last month. It was here in Prekaz province, just a few dozen kilometres from the capital Pristina, that a seven-year stand-off between the Serb-led authorities in the autonomous province and the mostly Albanian population came to a head. This was the birthplace of Kosovo’s war.

On 5 March 1998, the Yugoslav army launched an attack on the family home of Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) leader Adam Jashari. During a three-day long assault on their compound by Serb forces, 64 members of the Jashari clan were wiped out. It was a single eruption of violence, anticipating a descent into wholesale butchery.

There are many links that connect Skenderaj’s grim past with its more hopeful present. Most conspicuously the Bajram Aliu Stadium, and the team that plays there, Super League outfit FK Drenica, fly the flag optimistically for Kosovo’s future. The past, though, is a constant spectre.

Inside the freezing bunker that is Drenica’s clubhouse, president Daut Geci is solemn voiced as he explains the story of how the club survived the brutal Serb repression of the 1990s.

“There is a field just over there where we moved to play a lot of our games,” he says, standing and gesturing out of the window. The draft in here is bitter, and every word between us visibly carries on the cold air.

“I remember a game we were playing in Mitrovica in around 1997. Midway through we were interrupted by soldiers from the special unit of Arkan [the notorious Serb warlord] who entered the pitch with guns and stopped the game. When people realised who they were, they ran. They ran for their lives.

“Now, the players were young and they could run. They got away. But they caught the referee and some of the older fans who were less mobile and couldn’t get away from the pitch.

“They made those old people dismantle the goals and carry them around the field on their backs, just for fun. It was ritual humiliation.”

Jashari, the guerilla fighter whose life and death are so etched now in the DNA of this young country, had been a supporter of FK Drenica. The Jashari family compound was situated just over a kilometre from the Bajram Aliu, and the man who is seen by many as the father of the modern republic would often attend matches here. The rest of his time was devoted to preparation for the guerilla resistance to Serb rule.

“He would always watch us when he was able to,” says Geci. “The club was special to him.” That link is immortalised by an awkwardly framed picture of Jashari, which hangs just behind Geci’s head in the Drenica clubhouse. A memorial to the Prekaz massacre, visible from the bunker, sits where the house once stood. Parts of the original structure still stand.

The route back to Pristina from Prekaz is lined with martyrs’ cemeteries that animate the roadside with memories of the dead. Their number has never been agreed on, though most estimates place the total casualties of the war at around 12,000, with a further 900,000 displaced. The bodies of many of the dead have never been found.

Throughout the 1990’s, football had been inextricably caught up in the battle to assert Albanian nationhood. From the moment in 1991 that current Football Federation of Kosovo (FFK) general secretary Eroll Salihu led his teammates from FC Pristina in forming a breakaway football league independent of the federal Yugoslav set-up, Kosovan footballers began to suffer physical attacks simply for attempting to organise their own competitions.

The history of football in the region during this period is pockmarked by violent disruption. Football itself had become an unyielding act of defiance. When civil unrest collapsed into all-out war after the Jashari murders, the game was to form the backdrop to a drama nobody could have predicted.

In 1999, Genc Hoxha was one of Kosovo’s most recognised football names. A son of Gjakova in the west of the country, Hoxha made his name with the city’s leading club, KF Vellaznimi, in the 1980s before moving on to represent KF Liria in nearby Prizren. In the newly independent league’s maiden season in 1991, he had been named Kosovo’s footballer of the year.

By the time the war began, Hoxha had returned to Gjakova, living with his wife, parents, grandparents and two children, in a house just behind the city’s bus station.

Just after midnight on the night of 28 April, the family was woken by the sound of Serb soldiers breaking down their door. They were ushered outside into the street, where other families in the neighbourhood had been similarly herded from their homes and out into the night. It was freezing.

Hoxha didn’t see what happened to his family as he was thrown face-first against the wall of his house, the tip of a machine gun pushed against his temple. Then the interrogation began.

One of the soldiers, the one holding the gun, fired off his questions in Russian, knowing that very few people in this provincial backwater would have a second language. Hoxha was just educated enough to pick out a few words, sufficient to know that he was being asked to name his profession. Unable to make himself understood, he searched frantically in his mind.

“Oleg Blokhin,” he eventually blurted.

The Russian soldier’s ears pricked. Blokhin had been a Soviet football great, some say the greatest to come out of the lands behind the former iron curtain. The language barrier had, just for a moment, lifted. The Russian was interested now.

He withdrew his weapon, and beckoned Hoxha away from the street and round to the back of the house. Once they were out of earshot of the rest of the attackers, he addressed his prisoner in perfect Serbian. “You are a footballer?”

“Yes, I am a footballer,” Hoxha replied. The Russian solider paused.

“I don’t want to kill a footballer,” he said. “So here’s what is going to happen. I am going to fire my gun twice into the air, and you are going to fall to the ground. You will stay there for 10 minutes. Then you will leave this place.”

For a moment, Hoxha stayed silent. “Can’t I go back to look for my family?” he asked, struggling to process the rapidly changing situation.

“If you want to live, you will do exactly as I have said,” replied the Russian. Then he fired his gun twice into the Gjakova night, and Hoxha hit the ground, listening as the soldier’s footsteps carried him away. He heard too the final words exchanged between the Russian soldier and his Serb colleagues before they walked away.

“Is it over?” asked one of the Serbs. “Yes,” replied the Russian. “It’s over.” Then they left.

The next minutes and hours unfolded in a blur. Having obeyed the Russian soldier’s instructions, Hoxha went to a neighbour’s house to begin the desperate search for his family.

“I had assumed that the Serbs had taken them down onto the main street, away from the house,” he told me. Throughout our meeting, what struck me most was his calm bearing, as he matter-of-factly recanted the tale of the day Oleg Blokhin saved his life.

“At first I thought maybe it would have been better if they’d had killed me. I went over the road to my neighbour’s house, he was a footballer also, and we just moved then from house to house, waiting for the Serbs to return.”

By now, the streets of Gjakova were ablaze. Hoxha’s own house was burned to the ground that night, as the attackers scorched the earth that had played host to their crimes.

“Everything around us was burning, but we kept moving. The only thing we could do was move. We weren’t going anywhere. Just trying to stay alive, waiting for the Serbs to return.”

By 3am, three hours after the massacre had begun, the last Serbs had left Gjakova. A total of 372 people were killed in those first few hours of 29 April.

With the village smouldering, the remaining residents began the march into the centre of Gjakova, the war’s newest refugees, but far from being the last.

“We began the trek out of Gjakova, towards Albania,” said Hoxha. “Then two of my neighbours came and grabbed me and said ‘follow us.’ They didn’t say why, they just pulled me away.

“They brought me to a clearing within the crowd, and there were my wife and children. Everyone just started to cry. Everyone was hugging and crying. It was very emotional. After that we got on trucks and left Kosovo for Albania.”

The Gjakova massacre is thought to have been the largest of the conflict, at least in terms of numbers. A little over six weeks later, the first NATO ground troops entered Kosovo, signalling the end of a three-month aerial campaign and ushering in the first tentative signs of peace.

Today the Super League, like the country itself, is much healed. The league has been buoyed by the decision in May 2016 to bring the FFK into the Uefa and Fifa folds.

Speaking just weeks before the decision of the Uefa congress, president of FK Drita from the city of Gjilan, Fisnik Isufi, had told of how the clubs of the Super League had floundered for years in the football wilderness, scraping by with little financial backing and virtually no infrastructure.

“People do not see any long term light in achieving any kind of profit,” Isufi said in March 2016. “When I meet business I tell them that they can promote their company, that they might increase income.

“But it stays so close; no internationals, no outside games. When you don’t have any opportunity to promote your players then it’s very hard to make sales so you’re not very attractive for people who run businesses. They see better ways to generate money than in football.”

But this is a new era for Kosovo. Uefa membership has brought greater stability to the game here, as well as the added exposure through European competition that was lacking during the wilderness years. That isolation had been discouraging investment, but now the FFK is part of the European-wide football family, with all the commercial opportunities that brings.

It’s a far cry from the days when Geci’s FK Drenica teammates were chased from their makeshift pitches by Serb militia.

“The truth is that our club didn’t really survive the war,” he says, back in the clubhouse at Skenderaj in Prekaz. “We had to re-start completely. There was nothing left. No structures survived, only the pitch survived. Most clubs didn’t suffer in this way, because a lot of areas weren’t so exposed to the violence. But we were destroyed.”

The club did survive, though. That we are here in this draughty room, overlooking a rugged, unkempt football pitch is testament to that. Drenica were revived in the years following the conflict, starting again in the third tier but quickly rising to re-take their place in the top flight. Today, the team are scrapping for their lives just outside the Super League relegation places, but that phrase no longer carries the literal meaning that it did 20 years ago.

And Kosovo survived, too. As the last bus of the day disappears south out of Skenderaj, past the graves and the headstones too numerous to count back towards Pristina, the sun finally gives in and dips behind the shallow stands of the Bajram Aliu Stadium. And the air has never felt more alive.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments