As Iran has shown, the line between politics and football in the Middle East is a thin one

The inclusion of Masoud Shojaei and Ehsan Hajsafi in Iran’s provisional World Cup squad on Monday has sparked controversy in the country

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The announcement of the Iranian World Cup squad isn’t something that traditionally causes ripples of either excitement or consternation.

But as violence on the Gaza border continues and the fallout from the US's decision to open its embassy in Jerusalem gathers pace, the decision from the Iranian Football Federation to reintegrate two players who were previously banned for life has once again illustrated that the dividing line between football and politics is far thinner than Fifa portray it as being.

Masoud Shojaei and Ehsan Hajsafi were among the 35 players named in Iran’s provisional World Cup squad on Monday, despite both having incurred the wrath of the Iranian Football Federation back in August when they played for Greece’s Panionios against Maccabi Tel Aviv in the Europa League.

Although neither played the away leg in Israel – in a third round qualifying tie that the Greek side lost 2-0 – their participation caused huge controversy in the Republic, which doesn’t officially recognise the Jewish state.

“Hajsafi and Shojaie have no place in Iran’s national football team anymore....they crossed Iran’s red line,” said Mohammad Reza Davarzani, Iran's deputy sports minister, on state television shortly after the pair’s appearance against the Tel Aviv club in Athens.

Iran’s sports ministry said that the pair had refused to play in the first leg of the tie in Israel despite facing the threat of financial penalties from Panionios. But playing in the return match on Greek soil was clearly a step too far for the Iranian regime.

In reality, the would-be ban, which was never formally ratified, would have directly contravened Fifa regulation and could even have led to Iran’s expulsion from Russia 2018.

The provisional selection of both players for the World Cup at such a sensitive time in the region has, though, served to illustrate just how crucial success at the World Cup would be for an Iranian regime desperate to project a positive image of itself onto the global stage in Russia this summer.

The World Cup comes at a time when US criticism of the regime has once again been ratcheted up by Donald Trump following his country’s withdrawal from the Iranian nuclear deal struck in 2015. Iran, meanwhile, has, so far at least, only retaliated with words rather than weapons following Israeli air strikes on Iranian targets within Syria.

The selection of Shajaei and Hajsafi has, though, caused something of a stir, even though the former was originally recalled to national duty back in March after a seven-month hiatus.

“Iran, like most other Middle Eastern countries, is football crazy,” says James Dorsey, the author of The Turbulent World of Middle East Soccer and a senior fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies at Singapore’s Nanyang Technological University.

“This is the most popular form of popular culture in the country and as a result, political control of it is essential for the regime. In the last six or seven years you’ve seen the Revolutionary Guard moving into the management of football teams. They’re on the boards at a number of different clubs.

“When Iran qualified for the 1998 World Cup there was an absolute explosion of joy on the streets of Tehran – all the social norms that had been introduced were simply swept away.

“Some of those celebrations, at times, turned into anti-government protests. If you look at the protests you had earlier this year, a lot of the protests, again, started on the football field, particularly the ones that were started among ethnic minorities within the country.

“These protests started in the football stadiums and then spilled onto the streets and turned critical of the government. This shows just how significant football is and the fact that they’ve included two players who were barred because they have played against an Israeli side is equally significant.

“They’ve been installed at a moment of heightened tension between Israel, Iran and Syria.”

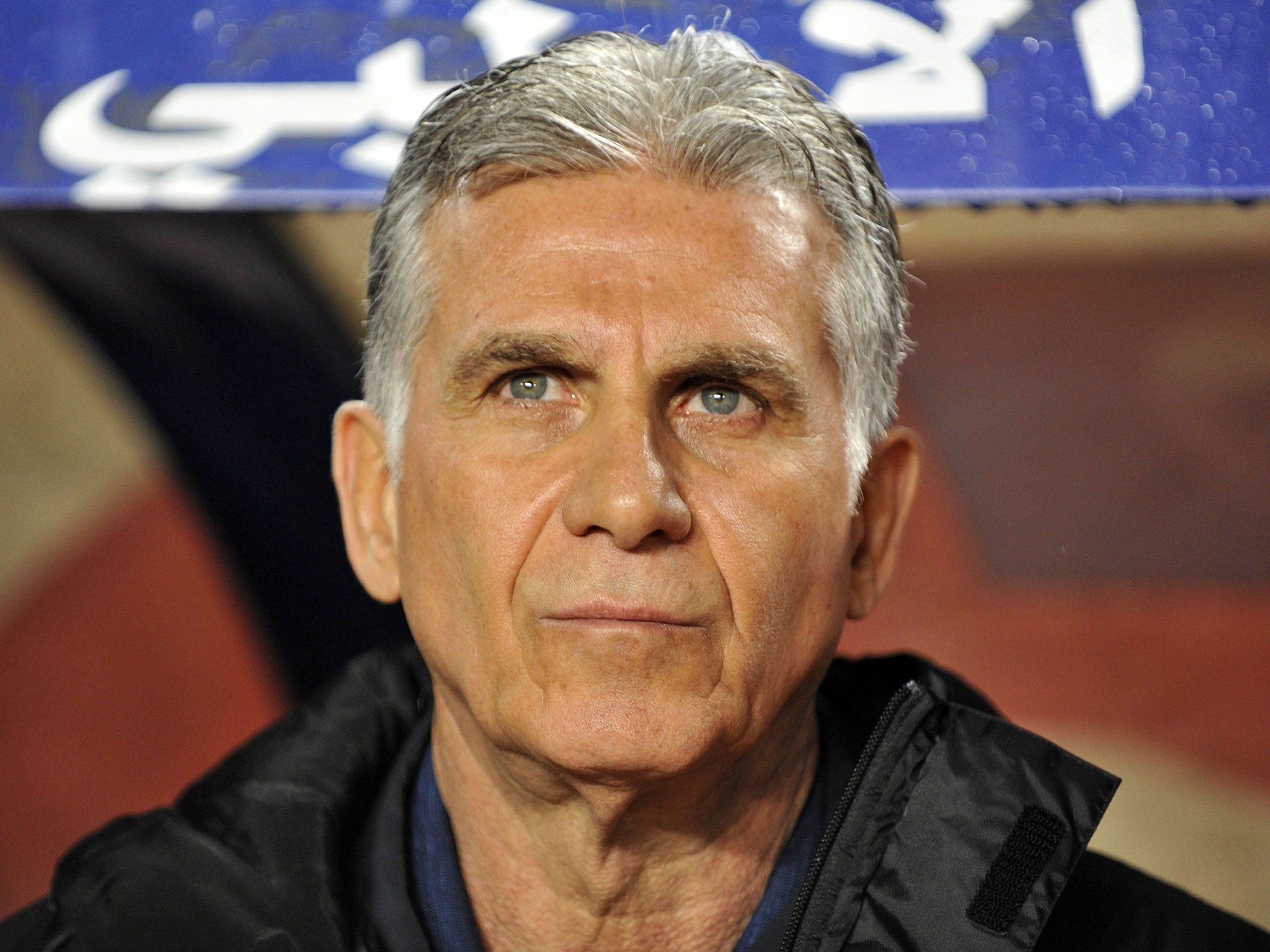

Their inclusion may, of course, be simple pragmatism from an Iranian Football Federation which already knows that Carlos Quieroz’s side face a mountainous task to progress from a group that includes Spain, Portugal and Morocco.

It might also be the result of the backlash from Iranian football supporters on social media criticising the rhetoric that emanated from senior figures within the regime after Panionios’s tie with the Israeli side.

It could even be Iran attempting to portray a softer side in the run-up to a tournament that has been less about football and more about the host’s apparent desire to upset almost every single nation playing in it.

Whatever it is, it won’t have escaped the attention of the country’s football authorities that while the US president issues veiled threats to those who don’t support the USA’s joint World Cup bid with Canada and Mexico for the 2026 tournament, Trumps' soccer-loving compatriots will be forced to watch on helplessly, and probably red-faced, as the likes of Iran perform in Russia.

Even a creditable third place in the group coupled with fighting performances from Team Melli against Spain and Quieroz's home country could be enough to see them welcomed home as something approaching heroes on the tarmac of Tehran’s Imam Khomeini airport.

And that would be quite some moment for Shojaei.

If he does make a return to the team it would represent a record third appearance at a World Cup finals for the now AEK Athens midfielder.

His work off the pitch, though, is likely to be more significant than his deeds on it. The 33-year-old was a high profile supporter of the so-called Green Revolution in 2009 and has also been a vocal critic of the ban on women attending football matches in Iran – a ban which dates back to the Islamic Revolution of 1979.

It’s believed that Shojaei brought up the ban during a meeting with Iran’s president Hassan Rouhani last June following the country’s qualification for Russia.

“I hope it happens very, very soon,” he said in a later interview.

That might be wishful thinking, although Dorsey says that Iran’s participation at major tournaments often brings the subject into sharp focus.

“Iran is the one country in the world where you’re not allowed women into the stadium for a male sporting event,” he says.

“It’s the one country that still maintains that. During the last World Cup there were issues of women watching matches in cafes. You would have the games broadcast in coffee houses and there were issues over gender mixing. This is another potential headache for the government.”

Football, like politics in the Middle East, it seems, is rarely straightforward.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments