The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

World Cup 2014: Chelsea and Brazil midfielder Oscar reveals the legacy of 1950

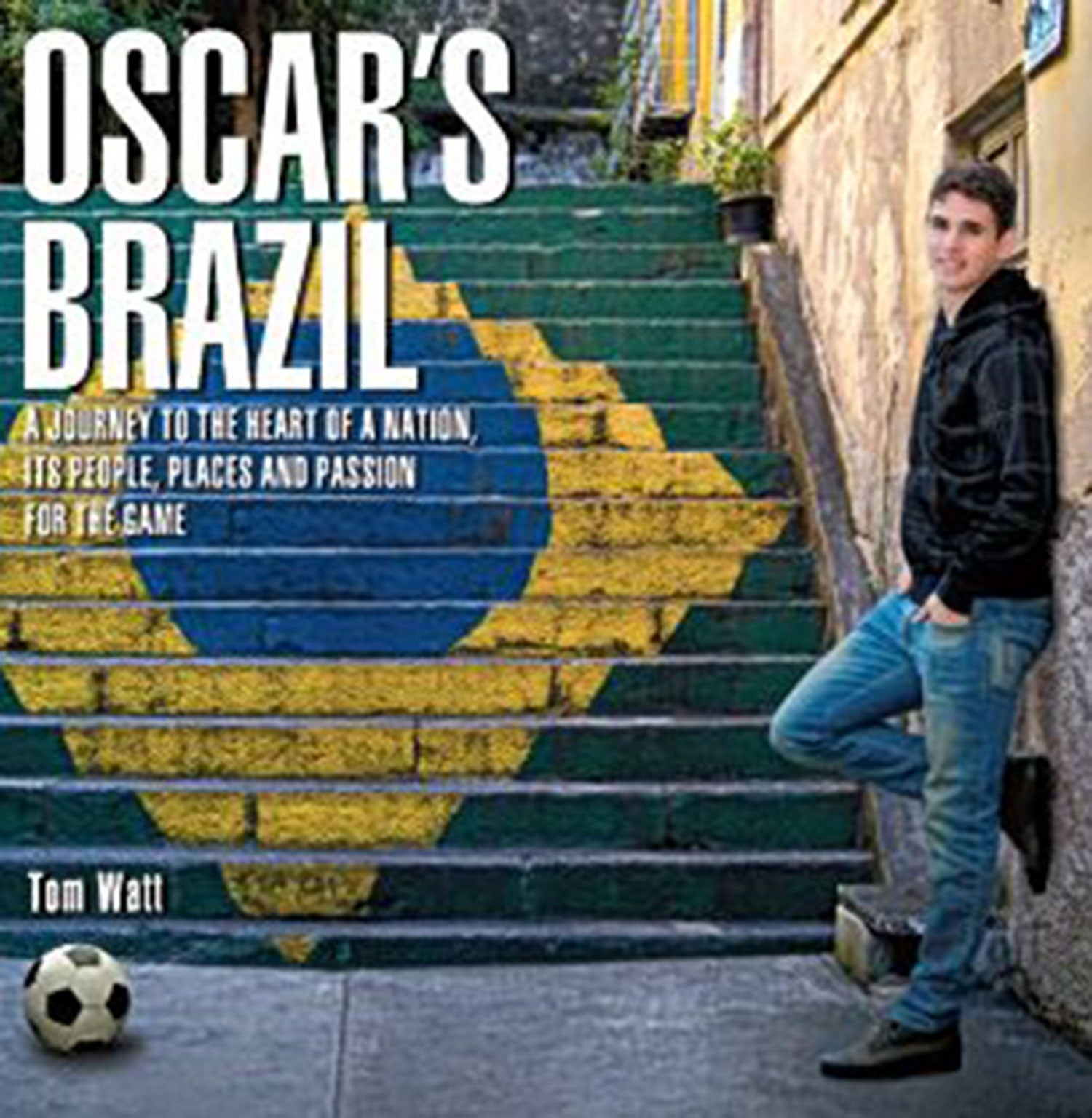

In these extracts from a new book, the Chelsea and Brazil midfielder Oscar and author Tom Watt set the scene for the coming World Cup by recalling the early days of Brazilian football, the life of a young player, the shock outcome when the country first held the tournament...and what it still means to those who carry the nation’s hopes

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Tom Watt on how beautiful game arrived in Brazil

“Football will never catch on, you can be sure of it,” wrote Graciliano Ramos, one of Brazil’s great men of letters, just over 90 years ago. “It is a temporary enthusiasm, a craziness, an obsession for many people, lasting perhaps a month. We have lots of our own sports. Why should we want to go poking our nose into foreign ones?”

Ramos was writing in the early 1920s, from the remoteness of Palmeira dos Indios, a small, lost inland town in Brazil’s impoverished north east. But at the same time, down in the south east, in the booming, cosmopolitan cities of Rio de Janeiro and Sao Paulo, a very different story was being told. Two years earlier, as tournament hosts, the Brazilian national team had won the South American championship for the first time (and would win it again in 1922). Songs had been written in celebration, poems composed. Parties had spilled out across the city’s streets. Here, football had started to take a grip on a country’s urban psyche, a grip that’s shown no sign of loosening ever since.

Introduced by the British, the game arrived with the cachet of First World prestige. Almost from the off, it was re-interpreted by the locals. Originally the preserve of a wealthy elite, football quickly caught on because of the game’s essential simplicity. Here was a game with very few barriers: given a round object and a space, anyone could play. And in Rio and Sao Paulo, lots of people wanted to play. The rapidly growing cities, with immigrants pouring in from Europe, the Middle East and other parts of Brazil, were an environment in which change was embraced. And so Brazilians – South Americans, indeed, because the same process was taking place in cities such as Buenos Aires and Montevideo too – came to the game with fresh eyes and open minds. Instead of the hard-running, “muscular Christianity” tradition of the British, they developed something far more sinuous and balletic, an artistic style of play ideal for a player with a low centre of gravity.

Oscar on his footballing childhood

I grew up in a suburb of Sao Paulo called Americana. Life was very different in a neighbourhood like mine compared to life in the centre of the city. You know, there are drugs and crime everywhere, and the threat of violence, but Americana was a calmer, more relaxed place. The problems weren’t anything like they are in the poorer neighbourhoods of Sao Paulo. I have three sisters, one a half-sister on my dad’s side. I liked where we lived – it was a good place to be a boy, a boy who liked football. Americana was safe enough that I could go off and play on my own in the park. Perfect: a little pitch to play on, with floodlights and everything. I could be out there all day, every day!

I lost my dad when I was three. He died in a traffic accident. My dad used to buy and sell things; you could call it recycling. It’s a very normal profession in Brazil. My mum was always a housewife, at home and there for us, but she used to make and sell clothes after Dad died. Mum raised us on her own but because, like her, my dad’s family were from Americana, she had help from them too. We were like one big family in many ways. Life wasn’t easy: we weren’t rich, my mum was on her own, but we were happy and Mum looked after us really well.

In different circumstances our situation might have been much more difficult but we had a house to live in, we had family around us. I’m aware, though, that there are lots of children in Brazil growing up without the support we had: in the favela there are a lot of boys and girls who are having to try and find their own way, without guidance or help, and in social and economic conditions that are much worse than I experienced as a boy.

Tom Watt on Brazil’s previous home World Cup

Unlike previous tournaments, the 1950 World Cup was not played to a knock-out format. Instead, the four group winners met in a final pool. Brazil were apparently unstoppable, playing with a breathtaking combination of style and athleticism, and blasting seven goals past Sweden before overwhelming Spain 6–1. Their final opponents were Uruguay, who had squeezed past Sweden after only drawing with Spain. A draw, now, would be enough to see Brazil crowned world champions for the first time in front of a capacity home crowd on the afternoon of 16 July.

In the build-up to their final game, the team’s training base was moved. Earlier in the tournament, Brazil’s players had enjoyed the relative tranquillity of a facility on the outskirts of the city. Now they were near the centre of Rio, at Vasco da Gama’s stadium just across a park from the Maracana. This was election year: the campaign – ultimately successful – to win a further presidential term for Getulio Vargas was in full swing. Brazil’s training base seemed to be doubling as the epicentre of national politics. The players were forced to gather to listen to speech after speech, with most of the candidates already hailing the Selecao as world champions. The local media did the same. So too the Mayor of Rio, Angelo Mendes de Moraes, on the pitch before the game kicked off.

The reward for such hubris would be tragedy. Uruguay, after all, were still Uruguay: a team who had never lost a match at a World Cup. Forgotten in the excitement of the occasion was the fact that this was a game between two well-matched teams. As it turned out, La Celeste were on the back foot for much of the game and, early on in the second half, Brazil’s pressure finally told: Ademir and Zizinho worked the opening for winger Friaca to score. Reflecting nearly half a century later, though, Zizinho would remember that triumph as the moment when Brazil started to lose their grip on the game: “It seemed that we had a collective drop in pressure. Our team stopped. It seemed that we had carried out our duty in the game. Our responsibility had ended there, when we opened the scoring.”

There were no substitutions permitted in those days. Brazil coach Flavio Costa tried desperately to shout instructions and encouragement to his distracted players. Inside the Maracana, though, 200,000 people were already celebrating, waving their handkerchiefs in the air – an adios! to their opponents – and chanting triumphantly. The coach went unheard. Until, suddenly, the stadium fell silent. Ghiggia set up an equalising goal for the Uruguayan centre forward, Schiaffino. Costa later described it as “a silence which terrorised our players. They felt responsible for this, and didn’t react”.

Less than 15 minutes later – and with only 10 remaining – Ghiggia raced away once more. Anticipating another cross, Brazil’s keeper, Barbosa, came off his line only for the Uruguayan winger to surprise him with a shot inside the near post. The underdogs in front, Brazil roused themselves and once more laid siege to the Uruguayan goal. But the crowd appeared to have lost all belief. Afterwards players from both sides commented on how quiet it remained around the huge and tightly packed bowl as Brazil went in search of an equaliser. Time, as always for the losing side, seemed to tick by with alarming and unforgiving speed. Uruguay held on. At the final whistle, the home crowd streamed away, most of them in tearful silence. Some sought ways to vent their frustration and anger, however. Newspapers were set on fire, as were pieces of timber left behind from recent building work. A bust of Rio’s mayor, the hapless and overconfident Angelo Mendes de Moraes, which had stood at the entrance to the Maracana, was found next morning floating in the nearby river that had given the new stadium its name.

Oscar on the legacy of 1950

It was an incredible thing: the defeat against Uruguay at the Maracana in 1950, the game they call the Maracanazo. I’ve never actually seen the pictures but it’s as if I still know exactly what happened that day. I understand the effect it had on the Brazilian people; we went on to win the World Cup after that, five World Cups. And we’ve won them everywhere else but, because Uruguay beat us, we’ve never won one at home. It just makes this year that much more important, for the people and for the players, too: a World Cup here in Brazil again.

I can’t say I know a lot about what Brazil was like, back in 1950! But I know the country has evolved and changed a lot. Football has changed, of course, but so too has everything else. The thing about 2014 is Brazil is known all over the world as the home of football, a particular kind of football: football that makes people happy. It’s not just the players, either. Brazilians are known as a happy people and people who are big fans of football. That will all be on show to the rest of the world at a World Cup in Brazil: our football, our country and our people.

What’s important is to recognise our responsibilities and take them seriously as players. But not to let the pressure inhibit us. When the whistle blows for kick-off, we have to make sure we let the joy in our football come through. If we do that, we know we’ll have 200 million Brazilians on our side, cheering us on. We have to be true to ourselves and true to our football ideals and not let the scale of the event, the importance of a World Cup in Brazil, stop us playing the way we all want football to be played.

So many Brazilian players now play overseas. It will make a World Cup back at home even more special. I’ve been playing in London, with Chelsea, for two years but I know what it feels like to play in front of Brazilian fans, a Brazilian crowd. All of us are the same: we’re passionate about our country. Whenever we have a holiday, we go home to Brazil, home to our families and our friends. So, now, to have a World Cup there? That will be a very special kind of homecoming indeed!

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments