The £380-a-month ghost at Qatar’s £26bn World Cup

Despite persistent protestations of innocence and integrity, the 2022 World Cup remains tainted by Fifa’s institutional corruption

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Mohamed Khalib stirred from a fitful sleep following a night shift as a painter in Qatar’s ceaseless construction industry. He opened the yellow curtain surrounding his bed, over which hung a soiled string vest and grey patterned socks, to find uninvited strangers burrowing their way into his life.

Two television cameramen advanced instinctively, with intrusive intent. Khalib recoiled, smoothed down his brown nightshirt, and politely answered three reporters, of whom I was one. It emerged he was 35, and had worked away from his family in India for 10 years.

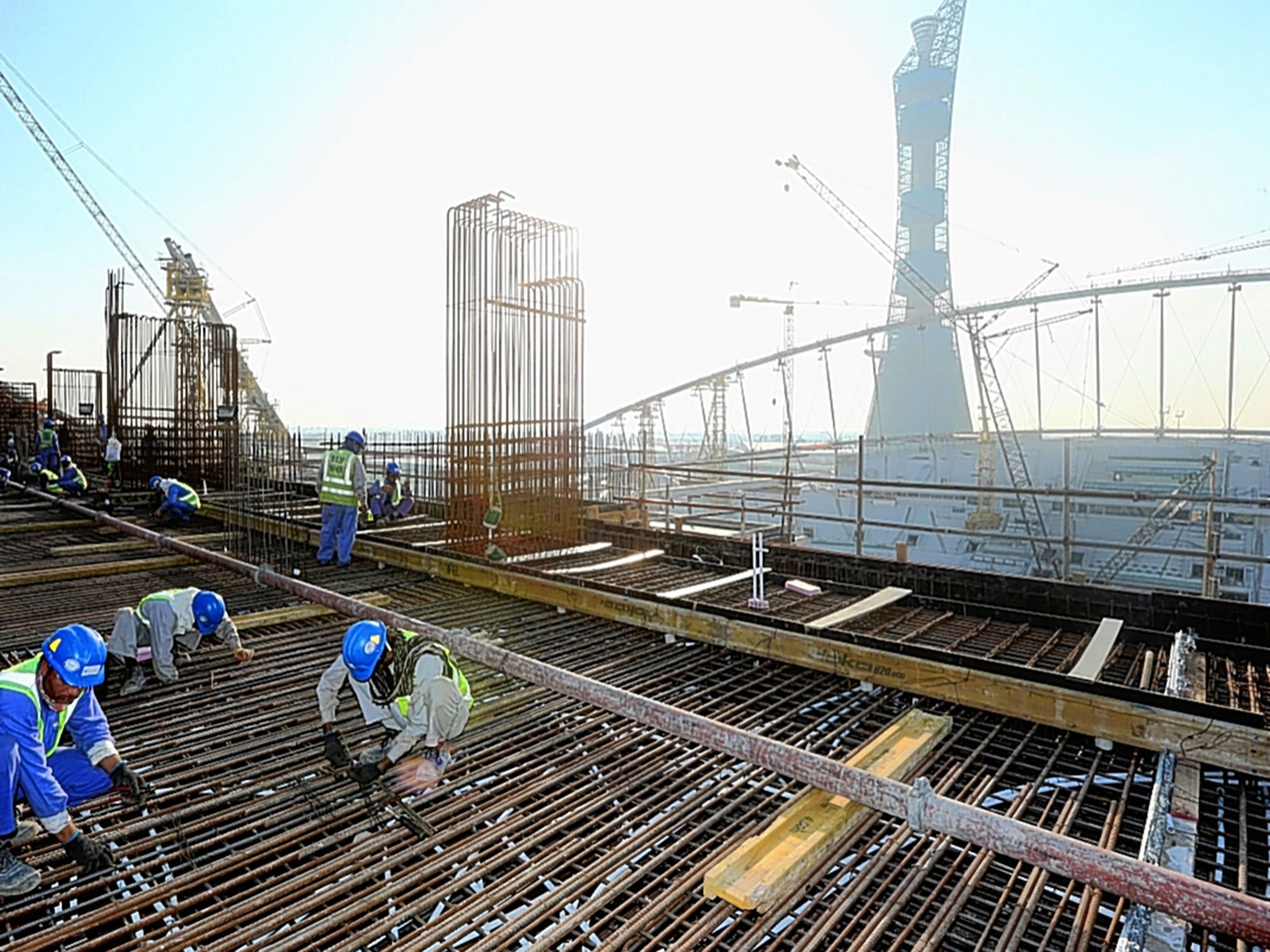

Here, in room G10 in Block 54 of the Asian Town labour city on the Western outskirts of Doha last week, was the ghost at the World Cup feast, the disenfranchised migrant worker who has the potential to be as significant as any multi-millionaire footballer.

Despite persistent protestations of innocence and integrity, the 2022 World Cup remains tainted by Fifa’s institutional corruption. Qatari organisers are also assailed by perceptions of human-rights abuse, a convenient platform for political point scoring in the grimy struggle to succeed Sepp Blatter.

There are, by current estimates, 1.75million expatriate workers in the immeasurably wealthy Gulf state. The main day shift assembles at 3.45am to be bussed to World Cup sites, but Khalib is one of the lucky ones; he earns £380 a month and has reputable employers, who pay for basic food and accommodation.

Many more endure slavish penury, having paid an extortionate recruitment fee in their home nations. They are unable to retrieve their passports to flee, despite such widespread practices being made illegal, and are routinely underpaid.

Asian Town, which will eventually house 100,000 men, represents Qatar’s answer to a global call for social change. A medical clinic is about to open on site; its initial contingent of six doctors will service 500,000 potential patients in Doha’s industrial zone.

Spiritual needs are met by Qatar’s second largest mosque, which can accommodate 6,500 worshippers. A cinema shows Bollywood classics. A 17,000-seater cricket stadium will host a World X1, featuring Kevin Pietersen, on 26 February.

To Western sensibilities, allotting Khalib six square metres of a fetid room he shares with three other men is demeaning. It represents a damning contrast when $30billion (£26bn) is being spent on six World Cup stadia, and a fading star like Xavi is paid £22million to play in an ill-attended local league.

To Middle Eastern eyes, viewed through the autocratic conservatism of the Qatari system, it represents the liberation of a traditional underclass who would be fortunate to be paid £30 a month in the South Asian labour market.

This is the fault line the region’s first World Cup straddles. Cynicism is the default mechanism on both sides of the cultural chasm. Even as lucid a leader as Hassan Al-Thawadi, the English-educated Anglophile who is in charge of World Cup preparations, complains bitterly about bias.

“I have answered a million questions about dirty money,” he insisted. “We have co-operated fully with the relevant authorities, in a very transparent manner. More than that, there is only so much we can do. In some areas we have been unfairly treated.

“There is a lot of criticism. A significant portion of the criticism comes from England, especially in terms of the stadium construction. This is not to say there are not issues on the ground, but other nations were granted the simple right of being listened to, and given the benefit of the doubt.”

His definitive challenge, to embrace sport as a catalyst for profound social change in the manner of South Africa during the transition from apartheid, is compromised by association with Fifa, whose culture of duplicity, hypocrisy and cronyism appears to have survived Blatter’s disgrace and the investigative scrutiny of the FBI.

All five remaining candidates in the Fifa presidential election are unfit for purpose, to varying degree, because they are scions of a discredited system. The charade allows Sheik Salman bin Ebrahim Al-Khalifa, the Bahraini who is narrow favourite to succeed Blatter, to position himself as a champion of reform.

London lawyers amplify his strident denials of association with domestic infringement of human rights, yet he was forced on the defensive again on Friday evening by embarrassingly timed links to a notorious match-fixer, revealed in the UK by Sky News.

He signed Amnesty International’s human-rights pledge, only after removing references to Russia and Qatar, and excluding passages related to abuse involving women and LGBT groups. His suggestion, in an Associated Press interview, that Fifa’s new president be elected in secret, and unveiled by acclamation, hardly augurs well for a new era of transparency.

The foundations of the successful 2022 bid were built upon toxic territory, despite its vision of being a positive, unifying force in a disparate, increasingly dangerous region. Since successive World Cups in Germany, South Africa, Brazil and Russia have been dogged by detailed allegations of corruption, it stretches credulity that Qatar’s bid was completely clean.

Al-Thawadi, a Liverpool fan who studied in Scunthorpe and Sheffield, is, at 36, the voice of a new generation. He will need the courage of his convictions, as a progressive influence in an opaque system pivoted by the absolute power of the new Emir.

The die is cast, in any case. Qatar is committed to positioning itself globally through sport. It will be a surprise if it does not host the 2028 Olympic Games; facilities are remarkable, and will be re-designed to IOC standards once the World Cup is over.

Al-Thawadi’s Supreme Committee for Delivery and Legacy this week issued a 46-page pledge to improve worker welfare. Yet being shepherded around Asian Town, where security guards control nine entry points to a 272-acre site which lies behind forbidding high metal fencing, was a troubling, voyeuristic experience.

Khalib, an inadvertent status symbol, was encouraged to speak his mind by Qatari officials when he was randomly disturbed, but candour and insight was unlikely in such heavily monitored circumstances.

We must never forget the human dimension. Out of common courtesy, and no little guilt, I lingered to shake Khalib’s hand, and thanked him for his tolerance. He smiled and said, “all is good”. It needs to get better, quickly, for the doubts to be dispelled.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments