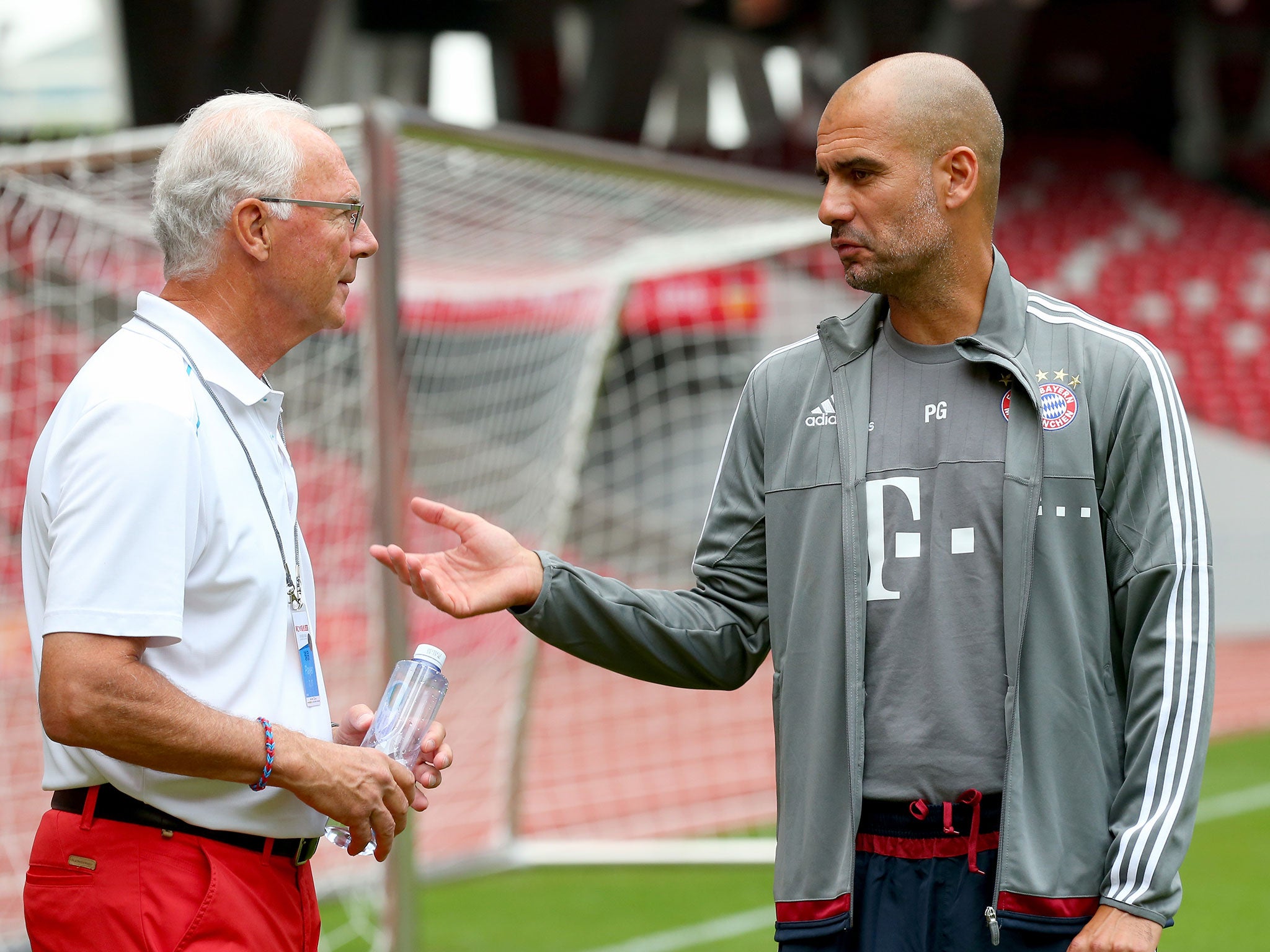

One of football's all-time greats, Franz Beckenbauer's legacy now lies in tatters following corruption allegations

In the space of 11 months, Beckenbauer has suffered a most dramatic fall - from national hero to the protagonist in one of European football's biggest scandals

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.At Franz Beckenbauer's house in Salzburg, there is peace and quiet. Its white walls are surrounded by the leafy suburb of Aigen, where the winding lanes have deep, green flanks. Down the road lies the old residence of the Von Trapp family, whose story would become immortalised in The Sound of Music.

A few streets away is the crumbling house of the art collector Cornelius Gurlitt, keeper of hundreds of priceless paintings thought to be destroyed by the Nazis. Gurlitt had quietly kept his art here for decades before he became an international news story in 2013.

Here in Aigen, the neighbours don't talk to each other a great deal. It is a place where the wealthy go for some peace and quiet.

The only time the peace and quiet isn't there in Aigen is when the reporters come. A few years ago, they came to sniff around Gurlitt's sorry little house, doorstepping the neighbours, imagining the treasure that might be hidden behind the locked door.

Nowadays, they only come for Beckenbauer. Gurlitt is dead now, and besides, the football legend is much easier to recognise and find than the hermit-like art collector. In the life of Franz Beckenbauer, there is no longer any peace and quiet.

There is always another question to ask Kaiser Franz, as he marches, tight-lipped, from his front door to the car. The lips of Beckenbauer and his spokespeople are often tight these days. They remained so this week, as details emerged of the 5.5 million Euros he secured through his work organising the 2006 World Cup.

That particular scoop is only the latest in a series of revelations which have left Beckenbauer red-faced. In the space of 11 months, the Kaiser has suffered a most dramatic fall. From national hero to the protagonist in one of European football's biggest scandals.

This is the man who led West Germany to two World Cups, first as captain and then as manager. The man whose wagging, critical tongue has long delighted and enraged German football fans. Hundreds of headlines have been written, dozens of storms in teacups unleashed by that jolly Bavarian lilt. As player, manager, commentator and agitator, Franz Beckenbauer has been the fuel in the engine of German football ever since the 1960's.

Beckenbauer cemented national treasure status in the early 2000's, when he led Germany's successful bid for the 2006 World Cup, before becoming chairman of the tournament organising committee. It is those roles, orchestrating Germany's so-called summer fairytale, which have seen his reputation dragged through the mud over the last year.

In October 2015, Der Spiegel alleged that the World Cup bidding committee had set up a slush fund through which they had bought votes on the Fifa Executive Comittee. The fund, said the report, was filled by then Adidas CEO Robert-Louis Dreyfus to the tune of 10.3 million Swiss francs. That money, it went on, had later been paid back to Dreyfus as 6.7 million Euros via a Fifa bank account.

The story sent shockwaves through Germany, and was met with furious denial from all quarters, including from Beckenbauer. “I never provided anyone with money in order to secure votes for our World Cup bid, and neither did anyone else on the organising committee, as far as I know.” The German FA (DFB) acknowledged that they had paid Fifa the 6.7 million Euros. As they and Beckenbauer remembered it, the payment had not been a slush fund, but simply a deposit for a later, much larger subsidy that Fifa would provide for the opening ceremony.

The problem was that nobody really did remember it. There were gaps in everybody's story, most notably in Wolfgang Niersbach's. A member of both the bid and organising comittees, Niersbach was now president of the DFB, and the first port of call for an explanation. On 22nd October 2015, he held a suicidal press conference in a bid to reassure the nation. The journalists simply sat back and watched as Niersbach publicly interrogated himself about the 6.7 million euros, and came up with no answers.

One month and one police raid on the DFB offices later, Niersbach had resigned, the first significant casualty of the scandal. Beckenbauer, meanwhile, had gone silent. As details emerged of an agreement he had signed with a certain Jack Warner just four days before the World Cup vote, Beckenbauer began the long process of retreating from public life.

It was around this time that the Kaiser's fall truly began. The initial revelations had not turned the public against Beckenbauer. That he was a sly old fox when it came to money was received wisdom anyway. After all, he had moved to Austria, where the tax rates were lower, back in 1982. The house in Aigen? The millions he had in capital? It was all part of his charm.

Even the suggestion that the DFB may have paid for votes was surprisingly unharmful to Beckenbauer. Much of the general public treated the Spiegel revelations with little more than a shrug. In the autumn of 2015, broad opinion had it that, even if Beckenbauer had bought the World Cup, it was worth it for such a ruddy good summer.

Beckenbauer had both his reputation and his friends to thank for the muted reaction. When you have done as much for the national game as Beckenbauer has, it is difficult to transform immediately into a pariah. The Kaiser is also one of many high-profile figures in German football who is close to Alfred Draxler, former deputy editor of Germany's biggest tabloid Bild. Draxler, who now edits sister publication SportBild, was one of the first to jump to his friend's defence. After the initial revelations, he said that Beckenbauer had spoken to him on the phone, and there had been no wrongdoing.

For several weeks after the Spiegel report, Bild seemed keen to defend the DFB and their former columnist Beckenbauer. They questioned the thoroughness of the Spiegel revelations, and Draxler argued repeatedly that the “summer fairytale” of the 2006 World Cup had not been ruined.

Only in mid-November did the tone begin to change. Perhaps it was the police raid which shifted Bild's perception, or perhaps it was the embarrassing performance of Draxler's friend Niersbach at that infamous press conference. Either way, they too were soon writing of the “great fall of the Kaiser”.

Beckenbauer, who had already elected relative silence as the best form of defence, retreated ever further into the safety of Aigen. His only public appearances were as a pundit on Sky Sport, an outlet perceived by some to be his other great media ally. Annoyed with the line of questioning on a Sky talkshow, one of the authors of the Spiegel report referred to them angrily as a “Beckenbauer broadcaster”.

Soon though, even the Beckenbauer broadcaster no longer employed the man himself. In March 2016, Sky announced that he would no longer feature as a pundit. It may well have been coincidence, but the split came in the same month as the report from Freshfields, the law firm contracted by the DFB to investigate the entire World Cup affair.

That Freshfields report didn't do much to help clear the Kaiser's name. It detailed that Dreyfus' 6.7 million euros had been paid via a Swiss bank account to the Qatari company KEMCO, apparently owned by former Fifa Executive Committee member Mohammed Bin Hammam. A chunk of that money, the report suggested, had passed through a separate bank account under the names of Franz Beckenbauer and his agent Robert Schwan.

Though that still didn't prove that votes had been bought, it certainly added weight to the argument. Beckenbauer himself had given an interview on Austrian television in 2010, explaining how Bin Hammam and the Emir of Qatar had helped to win votes for Germany.

“I'm not sure if we would have got the World Cup without the Emir of Qatar,” he said. “It wasn't about money. An envoy of the Emir is Mohamed Bin Hammam, who was later head of the Asian Federation and was then a member of the Executive Comittee. The Emir ordered him to help us get a few votes for our bid, and he did so.”

Hindsight is a wonderful thing. Coupled with Freshfields' account of the curious travels of the 6.7 million, that quote looks somewhat damning. Though there remained no proof that Beckenbauer had acted illegally, the headlines in March only hastened his retreat. Since his job at Sky ended, Beckenbauer's main communication with the outside world has been through his impersonal Twitter account.

The two most recent bombshells landed in the last two weeks. On September 1st, Swiss authorities announced they were investigating Beckenbauer for breach of trust and money laundering. He could face up to five years in prison.

Then there is the little question of the 5.5 million euros, which raised its ugly head this week. Naturally, it was Der Spiegel who broke the news. Beckenbauer, they reported, had been paid 5.5 million from the income of a sponsorship deal that the DFB and organising committee made with betting company Oddset in 2004. The money was not even taxed until the authorities chanced upon it in 2010. Only then did the DFB reimburse the German state, before invoicing Beckenbauer. He was able to pay up quietly.

Even for the apathetic German people, this was a betrayal. From the moment he took the job, Beckenbauer had always insisted that he had led the organising committee in a voluntary capacity. The latest scoop proved that he had been lying.

Paying less tax by living in Austria is one thing. That, at least, is an obvious trick. It is an open kind of arrogance which befits a legend of Bayern Munich. Even being accused of bribery was forgivable for many. In terms of popular appeal, his dishonesty over the Oddset money has arguably been the most harmful error.

His old friends at Bild have shown no mercy, as have his former employers at the DFB. New DFB president Reinhard Grindel called the 5.5 million euros “further proof that there was no transparency in the organising committee, and that the public were deceived.”

It was Green Party politician Özcan Mutlu, perhaps, who most concisely reflected the public mood. “As soon as he is healthy, Franz Beckenbauer must own up to what he has done,” he said. “I expect more backbone from the honorary and former captain of our national team.”

Beckenbauer, who is currently recovering from a heart operation, will not be hounded personally by the public or press just yet. But once he does recover, Mutlu's words will ring in his ears. His fall from grace has been astonishing. No longer can he rely on his reputation. No longer can he rely on his media allies. No longer can he rely on the sharpness of his tongue.

Most of all, he can no longer rely on the silence he has largely kept in the past months. Even the peace and quiet of leafy Aigen may not provide him with a way out this time.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments