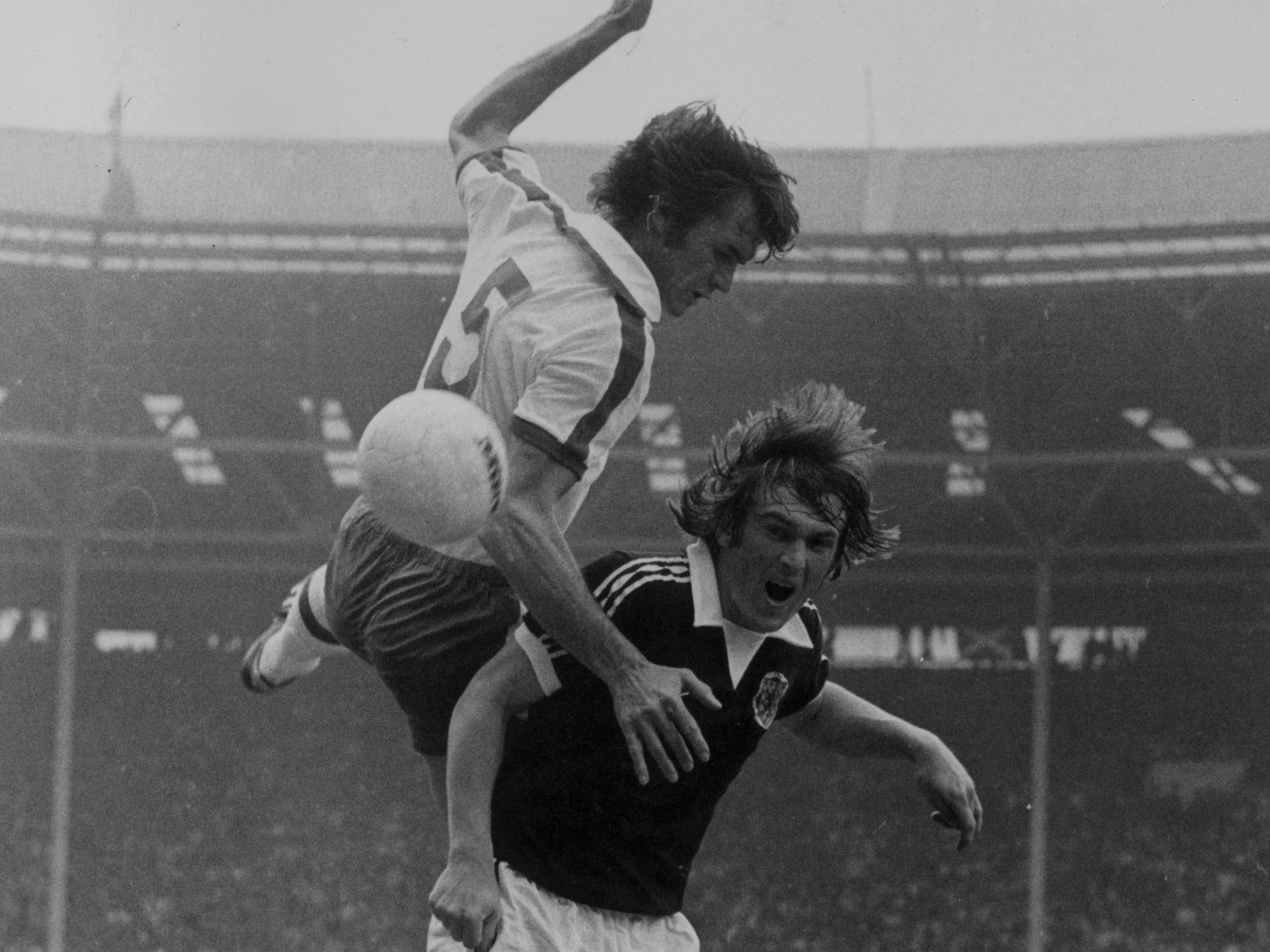

England vs Scotland: Lou Macari reflects on the iconic 1977 Wembley win the Scots expected to lose

Scotland ran out comfortable 2-1 winners over Don Revie's side

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Scotland were on their way to a second successive World Cup on June 4 1977, Ally MacLeod was already declaring they would win it and England had begun to forget what the experience felt like. Yet there was still a knot in Lou Macari’s stomach when the teams lined up in the tunnel at Wembley for the Home International match which would become iconic.

“I would never say you went into an England game with confidence,” Macari says. “Our record against them was so poor. There was always some apprehension.” His recollection bears out a record that has never allowed the Scots to laugh in the face of the English. The pair of back-to-back wins they recorded over Don Revie’s side in 1976 and 1977 has only been achieved six times since 1897 and not once repeated to this day.

Scotland’s great accomplishments against the auld enemy have always had much to do with managers and it was certainly true of that day. Willie Ormond - familiarly known to his players as Donny Osmond and a leader who found it difficult to handle the bigger names like Billy Bremner - had just been replaced by extrovert, publicity-seeking MacLeod, who could hardly have been a greater contrast.

It was the stock of Scottish managers, and therefore players, in the English club game which made the side such a force. Kenny Dalglish, Joe Jordan, Don Masson, Bruce Rioch and Gordon McQueen all started the 1977 game, with Macari and Archie Gemmill on the bench – an array which reflected the presence of Scots in almost every self-respecting First Division dressing room.

When Macari had left Celtic for Manchester United in 1973, he found himself among eight Scots in the starting line-up on debut - a 2-2 draw with West Ham United at Old Trafford in January that year. Alex Stepney, Bobby Charlton and Tony Young made up the numbers. “That indicates the Scottish presence,” he says. “Where foreign players are now wanted, Scottish players were sought after, then. The presence of Scottish managers had so much to do with it.”

Jock Stein, Macari’s Celtic manager, had actually lined him up for Liverpool, owing to his own friendship with Bill Shankly, though it would be another Scot, Tommy Docherty, the diminutive forward signed for instead. Docherty was himself hugely admired by many of the Scottish players, who regretted his departure from the national job.

“There was a currency of Scottish players and managers and that meant huge competition for a place in the Scotland team,” says Macari. “The original squad Ally named for the 1978 World Cup had 80 players in it and when I looked the players I was directly up against – Rioch, Masson, Gemmill, [Asa] Hartford, [Graeme] Souness and Gemmill - I wondered how I was going to make the cut, Manchester United player or not. When it was whittled down to 40, I had even more doubts about making the final 24.”

Every player felt that the 1977 Wembley match might influence the new manager’s thinking for Argentina and McQueen and Jordan, Leeds United teammates at the time, did themselves no harm. MacLeod had been working on a free-kick routine all week which was no more complicated than Jordan making a run to the front post, to distract from McQueen’s run to the back. (England manager Don Revie had been worried about the pair and his own training sessions entailed practicing repelling them, with goalkeeper Joe Corrigan pretending he was McQueen.)

Hartford always took beautiful free kicks and found McQueen to put Scotland ahead before the interval. Dalglish finished the job with a scrambled effort just before the hour and Mick Channon’s penalty kick was only a consolation. The 2-1 scoreline flattered England. And then came the iconic pitch invasion, which saw Scottish fans sitting on and breaking a crossbar and taking Wembley turf back north.

“I tried to get off the pitch but there was no way to do it,” says Macari, who’d arrived for the injured Jordan after 43 minutes. “The old tunnel at the stadium was too far away. We just got mobbed and to be honest we had no problem with that.

“They were simpler days. There was no system for playing the English. Jock Stein had won the European Cup with Celtic in 1967 without a system and that’s how it was. There was no talk about the opposition. You would not have sat you down and even tried to tell Joe Jordan, Kenny Dalglish or Asa Hartford how to play the game. You went out, played in your position and gave 90 minutes of graft.”

If anything, it was England who overcomplicated things. Several of the England team would later reveal in autobiographies how they found Revie – or ‘The Revs’ as he was known – suffocating with his attention to detail and demands that they join in his bingo schools.

The 2-1 win at Wembley sent the Scots supporters towards the Argentina World Cup with towering self-belief, fuelled by MacLeod and his persistent claims that ‘Ally’s Tartan Army’ would win the trophy. The nation’s tournament ended abruptly, amid defeat, a drugs scandal and tears. A mere 18 months after Wembley, McLeod was gone. They were remarkable days for a small football nation. “I don’t think even Ally could believe our success,” Macari reflects.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments