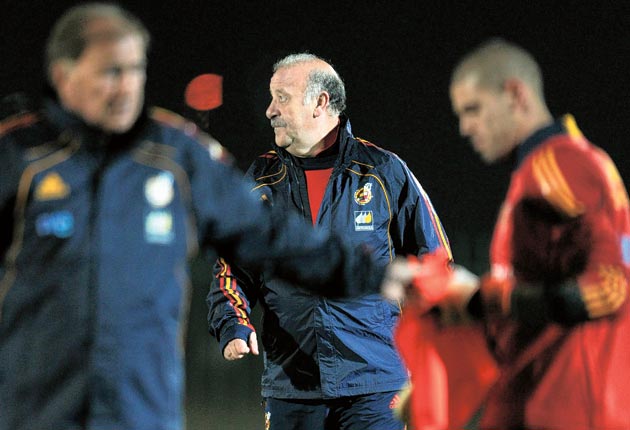

Del Bosque: Spain's quiet conqueror

He has proven himself to be a successful player and winning manager – but only now is a nation warming to its unassuming coach. Jimmy Burns turns the spotlight on an reluctant hero

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Few of the protagonists in South Africa have resisted the seduction of World Cup stardom with the ease of Vicente del Bosque.

A caricature of a pensionable Guardia Civil keeping a watchful eye from the dugout, the Spanish coach is overweight, balding, moustachioed. His team may have set pulses racing on the field, but in a football scene where the cult of the manager is built on virtuoso La Liga performances from Johan Cruyff to Pep Guardiola at Barcelona, and Jorge Valdano via Fabio Capello to Jose Mourinho at Real Madrid, Del Bosque has been respected rather than venerated, never generating a mass following. To fellow Spaniards he has been a difficult man to get excited about.

But that is changing. Del Bosque has joined Carles Puyol, David Villa, and young Pedro Rodriguez as one of the national heroes.

"Del Bosque no longer has any critics," announced a headline on Marca.com, the popular Spanish football site, over an article by Emilio Contreras, one of its senior reporters in South Africa. Contreras makes the point that few Spaniards really believed Del Bosque could manage to improve on Luis Aragones' achievement two years ago, when he led Spain to the European Championship. It was too tough an act to follow for a nation still cursed with the label of underachievers and for a man whose success at Real Madrid had faded into history with the ascent of the new Barcelona "dream team" under Guardiola. Spain's less than impressive first two weeks in the tournament, with the early defeat by Switzerland, fuelled the sceptics. Del Bosque was given a bad press.

Now he is being judged with the evidence of hindsight. "He has been right all along," wrote Contreras in the late hours of Wednesday, "in his blind faith in Iker [Casillas, the Spanish goalkeeper and captain], in his gamble on the Xavi Alonso-Busquets partnership, in the freedom he has given Barça's Xavi, in his decision not to insist on starting with Torres, in his ability to make all the players feel partners of a team's success." That alone is a victory for one of the most intelligent and sensitive men of the game, a man whose rarely told personal story explains much about Spain's success in South Africa.

I began to come to know and understand Del Bosque when researching a book on Spanish football, coinciding with David Beckham's move to Real Madrid. Del Bosque was replaced by Carlos Queiroz at the start of Beckham's first season with Real Madrid – seen by Florentino Perez as too quiet, not tough enough to be trusted with the galacticos project. This despite the record of winning the Champions League twice, La Liga twice, the Uefa Cup during four seasons in charge. He never failed to make the last four of the European Cup. It was the most successful period in Real's modern era.

Unlike Beckham or his replacement, Queiroz (now Portugal's manager) he has lived and breathed Real Madrid most of his professional life, first as a player straddling Francoiste and post-Francoiste Spain. A defender at the Bernabeu for 14 years, from 1970, he was capped 18 times for Spain, including their characteristically disappointing run in Euro '80, where his side failed to make their way out of the group.

I had been warned that Del Bosque was a retiring kind of guy who distrusted the media and valued his privacy. But a friendship I had struck up with some of the Real Madrid veterans helped change that. And fortuitously, Del Bosque seemed to know and admire my late Spanish grandfather, a liberal intellectual named Gregorio Maranon. It was a calling card too good to turn down.

A visit to Del Bosque's spacious Madrid apartment, in a quiet residential block within a five-minute drive of the Bernabeu, revealed a sitting room complete with predictable totems of success – silverware and plaques, among them one naming him the best football manager in the world. But it was also taken up with simpler pursuits, like his young handicapped son's computer course in Basic English, and surprising touches of humour such as a cartoon effigy of Juan Gaspart, one of the most disastrous presidents in the history of FC Barcelona, smiling, like a Goya witch.

Del Bosque was born in 1950 in Salamanca, in Castile, the same region as Madrid. I asked him then if a sense of geography is important to him, and his words have returned to me throughout this tournament. "I think the climate, the society in which you're born into, defines much of your life – in that sense I've considered myself a classic Castilian all my life," he answered.

What did he mean? I thought of what the legendary Real Madrid president Santiago Bernabeu had once said about what made Castilians better – that they had bigger and more rounded cojones than other Spaniards. But Del Bosque put it slightly differently. "I would say we are people with a sense of responsibility, somewhat august, cold, quite serene, without great eccentricities."

And yet Del Bosque has more Catalans than Castilians in his squad – and Catalans claim to have within them rauxa, an uncontrollable emotion, an outburst, any kind of irrational activity. Watching the Spanish squad on Wednesday, with its seven Barça players, was to get a sense of that.

The ever-diplomatic Del Bosque was the perfect choice to strike a balance between the old and the new when he took over from Aragones. Spain had just had their finest footballing hour but a queue was already forming full of young players ready to replace the internationals who had just been crowned European champions.

The Barcelona trio, Pedro, Sergi Busquets and Gerard Pique, have all come in. But it has all been evolution over revolution. There was no dramatic axeing of a Beckham-type figure that marked Steve McClaren's appointment. He even managed to bring the fiery Catalan Victor Valdes in as third-choice goalkeeper. On form alone Valdes was an obvious choice but many believed he would rock the boat if named in the squad but not picked to start. With Del Bosque's calming influence on deck, no one rocks the boat and Valdes has been impeccably behaved, despite watching the tournament from the bench.

Like me, Del Bosque was born into a post-war Spanish generation that while still in childhood had begun to glimpse the beginning of a better future while destined to remain forever conscious of the memories of the Civil War, of our elders and the hardships that they had had to put with for our sakes. Did he remember how isolated from the rest of the world Spain seemed when we were growing up?

Del Bosque told me: "Of course one felt it. I don't like to talk about this because it seems to identify one politically, but I remember my parents feeling very insecure about everything that was going on, speaking in whispers about certain subjects."

In a rare personal revelation, Del Bosque then went on to tell me about his father. "He was radical, he had progressive ideas. He was caught up in the Spanish Civil War, taken prisoner by the Franco forces and served a sentence. You see he was a pure blooded Republican. He worked as a clerk for the national railways. He used to talk to me to convince me that nothing of what he lived through should ever be repeated... I think we Spaniards of today are not sufficiently thankful to his generation. With every day that passes the frontiers are disappearing. A lot of those who lived the drama of the Civil War have died – that has helped cure the wounds."

Del Bosque seemed slightly irritated when I asked him whether it was fair to have once considered Real Madrid Franco's team. "Not especially. Anyway, Real Madrid was a football team. It was outside politics. It's a simplification to call it pro-Franco... Real Madrid is pluralist, it's got a huge number of followers of all tendencies," he answered.

He thinks much the same of the current Spanish squad, despite the enduring rivalries at club level.

Bringing people together – it is the hallmark of a Spain side that has thrived on its own harmony in South Africa, with no sign of tension between the boys of Barça and the players from Real Madrid.

Del Bosque's performance has been understated throughout. Accompanied by his wife, Mari Trini, and three children – two boys , Vicente and Alvaro, and daughter Gema – he has conducted himself like an ordinary family man, taking souvenir snap shots of some of the players or getting his sons a signed shirt, between meals and training sessions.

If no complaints about Del Bosque have leaked from the dressing room it is because there aren't any. He is not the controlling type. If Del Bosque himself has shown remarkable self-restraint in not displaying favouritism to any one player, it is because he has seen all the players he has picked, not just Xavi, Puyol, and Alonso, increasingly doing what is expected of them, or "sweating the shirt", a phrase he grew up with as a young defender. Only Fernando Torres has underperformed, but Del Bosque has made a point of not holding this against him in pubic, blaming it instead on a struggle to return to full fitness after last season's injury.

Whatever happens, Del Bosque will be remembered for having achieved something no other coach has achieved, taking Spain to a World Cup final. "Del Bosque is one hell of a coach," concluded Contreras in Marca, aptly summing up the national mood.

Jimmy Burns is the author of 'When Beckham went to Spain', 'Barça: a People's Passion', and 'Maradona: The Hand of God'. www.jimmy-burns.com

Roll of honour: Will Del Bosque or Van Marwijk join these World Cup-winning coaches?

1930 Alberto Suppici (Uruguay)

Led South American side to inaugural World Cup on home soil aged 31, having controversially dropped goalkeeper Andres Mazali for disciplinary reasons.

1934 & 1938 Vittorio Pozzo (Italy)

The only coach to have won two cups. Passionately involved, even sitting next to the Czech goal during first success, as hosts in Rome.

1950 Juan Lopez Fontana (Uruguay)

Former medical assistant who learnt his trade under Suppici. Beat hosts Brazil in the final pool match in what was in effect a winner-takes-all game.

1954 Sepp Herberger (West Germany)

Managed German team either side of the war, even keeping in touch with players during hostilities. Rewarded with unexpected triumph in Berne.

1958 Vicente Feola (Brazil)

Introduced Pele, then 17, on to the world stage. The teenager scored a hat-trick as Brazil thrashed Sweden 5-2 to become the first team to win outside their own continent.

1962 Aymore Moreira (Brazil)

Much travelled 50-year-old former goalkeeper, who steered Brazil to victory over Czechoslovakia in Chile, Garrincha shining in the absence of the injured Pele.

1966 Sir Alf Ramsey (England)

Strict disciplinarian who played in the infamous 1950 World Cup defeat by US. Successful Ipswich manager who promised to win the World Cup with England, and did.

1970 Mario Zagallo (Brazil)

First man to win the trophy as player and coach, having been on left wing in 1958 and 1962. Oversaw arguably the greatest of all teams, including ex-team-mate Pele.

1974 Helmut Schön (West Germany)

Born in Dresden he was devastated by group stage loss to East Germany and players are said to have assumed partial control. If so, it worked as they beat Dutch in final.

1978 Cesar Luis Menotti (Argentina)

Chain-smoker and believer in attractive football who urged his team to turn away from brutal excesses of Argentine football in the Sixties and reaped reward.

1982 Enzo Bearzot (Italy)

After an uneventful playing career, Bearzot became a successful coach. Encouraged attractive football, but also picked hero Paolo Rossi despite a match-fixing scandal.

1986 Carlos Bilardo (Argentina)

Spent 12 years at club sides before becoming national manager. Inspired by virtuoso displays from captain Diego Maradona, La Albiceleste swept to a second title in eight years.

1990 Franz Beckenbauer (West Germany)

"Der Kaiser" became the second man to win as player and coach. He topped that by securing hosting rights in 2006.

1994 Carlos Alberto Parreira (Brazil)

Successful, but unloved at home after he put practicality ahead of the jogo bonito to secure Brazil's first title for 24 years. Coached South Africa in 2010.

1998 Aimé Jacquet (France)

In leading a multicultural team to victory on home soil, their first, Jacquet (right) confounded the fierce critics who opposed his appointment and team selections.

2002 Luiz Felipe Scolari (Brazil)

Much travelled 54-year-old finally landed the national job in 2001 with Brazil struggling to qualify. Steered them to an unprecedented fifth world crown in Japan.

2006 Marcello Lippi (Italy)

After a hugely successful career at Juventus, winning five league titles and a Champions League, Lippi seemed to cap his career with this win. Then he returned for 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments