Copa Libertadores: Victory for Carlos Tevez with Boca Juniors will crown one of football's most storied careers

Tevez has divided fans both in Argentina and abroad, but it is easy to forget just what a supremely talented footballer he is

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Once again, Carlos Tevez’s teammates could scarcely believe what he was doing. This, however, was for different reasons than usual. A few months into the Argentine’s more contentious second season at Manchester United in 2008-09, the entire playing squad were given gifts of watches from new sponsors Hublot. The pieces were worth around £10,000 each, and the players were naturally carrying them away as one of the customary trappings of the job. Not Tevez, though. He looked at the watch with a disinterested expression, as if to say “what am I supposed to do with this?”, before leaving it there untouched.

It’s a little story that goes against a lot of perceptions of Tevez, all the more so because this was just a few months before he would move to Manchester City in one of many controversial moments that revolved around obscene money, and characterised an often contradictory and sometimes complicated career.

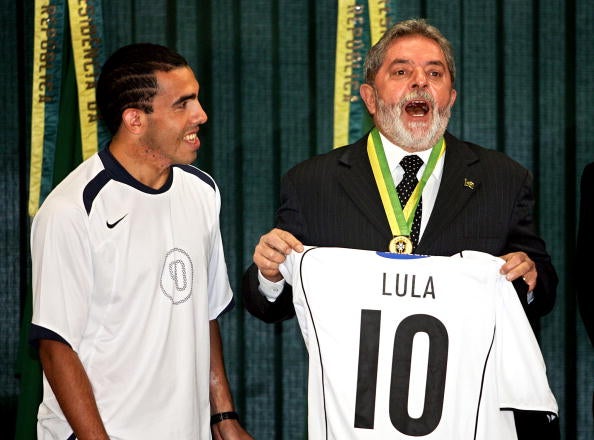

That career could be set for a newly defining feat this Saturday, with the 34-year-old playing for Boca Juniors at River Plate in the second game of the last ever two-legged Copa Libertadores final. If his side can turn the 2-2 first-leg at the Bombonera into the ultimate victory over their eternal rivals, it will be a rare instance of a South American star having their true legacy moment for their boyhood club, and that in a career where the game’s greatest trophies were anything but rare.

That, however, is just another complication when it comes to reflecting on Tevez’s genuinely massive contribution to the game across 17 years. In South America, he is mostly seen as the great romantic hero, the “Jugador del Pueblo” – player of the people. In Europe, he is widely seen as an embodiment of everything wrong with the game, and a symbol of its greed.

Those who know him, like former teammate Nicolas Burdisso, would say the European perception is really the problem of other people capitalising on Tevez’s “hunger”. It is a hunger that has already brought one Champions League, one Libertadores, eight league titles at five clubs across four different countries as well as another seven major trophies. He is the second most decorated Argentine player ever after Leo Messi, and one of very few players in general to have won both the Libertadores and Champions League.

Against so much silverware, though, there were so many controversies. Even beyond how he became a personification of the problems of third-party ownership, there was the “chicken dance” to mock River Plate in the 2004 Libertadores semi-final; the staggering move to West Ham United with Javier Mascherano; the legal case surrounding his remarkable feat of almost single-handedly keeping them up; that move to City and the “welcome to Manchester” sign; the row with Roberto Mancini and long absence from the team; Juventus’ anger about his eventual move to China; a therapeutic use exemption for betamethasone in the 2010 World Cup and then the highly questionable challenge that led to Argentinos player Ezequiel Ham badly breaking his leg.

England alone has seen him achieve the rare feat of succeeding supremely at three very different clubs, but you wouldn’t really think it for how he is remembered. He rarely comes up in “best foreign player” Premier League debates, even though he did something few English players even manage.

His long-time Boca teammate Rolando Schiavi agrees with Burdisso and is in no doubt about his legacy.

“He’s triumphed everywhere, left his mark everywhere, been a champion everywhere, and is one of the greatest players Argentina have ever had,” Schiavi tells The Independent. “All his teammates loved him.”

One figure who has worked at the top of the European game paints a different picture. “He’s maybe the archetypal football mercenary. Most teams would welcome his talents. Few would miss him when he leaves.”

Throughout all of this, and as far back as when he first left for Corinthians at the age of 20, Tevez would routinely say he wanted to be back at Boca “within a few years”. It only adds another layer to this final. He actualy thought he’d return by 25 or 26. It would be his immediate answer when asked how he saw his career panning out, and one of the few things a generally quiet bloke would get excited about, as he would enthuse about “the best atmosphere ever”, about that rivalry with River. At every house he moved into, Tevez would ensure the main wall was adorned with a huge picture of himself and Diego Maradona. The connection has always stayed consistent, but not everything else has.

Once adored and endorsed by Maradona, Tevez has this summer heard Argentina’s great legend speak out against him, for reasons that only add to the complications surrounding that legacy.

***

Tevez has been so characterised by raw aggression and controversy, that it is easy to forget just what a supremely talented footballer he is. That talent was why he was initially seen as an heir to Maradona before Messi, and why he made his full debut for Boca as early as 16 in 2001, having gone there – of course controversially from All Boys – as a youth in 1997.

Burdisso went there as a teenager at the same time, and left at the same time in 2004, so knows Tevez better than the most.

“From the first moment he trained with us, we noticed something different straight away,” the centre-half says. “What most struck was his influence. His capacity to decide games on his own was extraordinary.”

It was that which was so crucial in Boca’s run to the 2003 Libertadores, and that which saw him score in the semi-final against River in 2004, bringing that notorious “chicken dance” celebration that just adds an extra layer to this year’s final. The obvious interpretation was of mocking River’s history of choking – as chickens, “gallinas” – but then-teammate Schiavi puts it more down to instinct than intent.

“He was in the moment,” Schiavi says. “We were all so nervous. I think he did it without consciously realising, since it was such a release of emotion. The ref saw it differently and sent him off.”

It certainly saw the release of a lot of anger, and outright threats, because of all of the furore around such a highly-charged – and violent – fixture. But Tevez remained unaffected, unrestrained.

“Nothing ever seemed to faze him,” says Ciaran Simpson, a Mancunian football translator who spent every working hour – including “whispering dressing-room bollockings into his ear” – with Tevez in that season at West Ham. “If you’re from somewhere as dangerous as he is, everything will seem fine.”

No matter where in the world he’s gone, it’s always been impossible to detach Tevez’s career and entire personality from where he grew up: the neighbourhood of Ejercito de Los Andes, better known as “Fuerte Apache”. Simpson recalls how, when talking about the differences in where they came from, “Mascherano would say he heard cows while Tevez would say he heard gunshots”.

The area is so dangerous that the Independent could not find a taxi company that would even drive through there in the days before the Libertadores final second leg, and was abruptly advised not to even try.

Familiarity with a place renowned for such violence – almost visually reflected in a scar on his neck that was actually down to a childhood accident with boiling water – was why one City figure denied he ever had a reported fight with Roberto Mancini.

“If that happened, Tevez would have killed him.”

That capacity for taking everything that followed his formation “in his stride” was why he was able to perform at the same level through so many controversies, through so many clubs; why he could leave Argentina for Brazil and win the title with Corinthians at the mere age of 20 and then succeed through so many different highly pressurised situations in England: a relegation battle; a relentlessly successful established club; an ambitious new super-wealthy project.

It was ironically at the lower end of the Premier League with West Ham that Tevez would encounter one of his few periods of struggle. It’s easy to forget now how sensational that move with Mascherano to Upton Park in 2006 was, just how many questions there were about how a club of such resources could make it possible, but Simpson doesn’t believe the poor early form was down to that or even any adjustment to a new situation. The latter was never a problem. Tevez had too much adaptability as a footballer, too much persistence. The forward would merely remark how small the stadium seemed, but was generally just trying to get fit again. Tevez wasn’t in good condition when he arrived. As so many have said about him, he was so selfless that he would play through pain – and injections – and in any position.

What did eat away at him was the fact it was March 2007 and he still hadn’t scored. So, he had a target – one which informs how he so lives for occasions like Saturday’s SuperClasico. With West Ham due to meet Tottenham Hotspur in the league, Tevez that week turned to Simpson and said: “On Sunday, it’s the Clasico, no?” He was ready for the derby, and had been quietly readying a particular free-kick, getting Simpson to set up walls on the training ground. It paid off. Against Spurs, Tevez scored the first of six goals in 10 games that were crucial to keeping West Ham up and securing a move to Manchester United.

There, Tevez would become part of a sensational attack with Wayne Rooney and Cristiano Ronaldo up there in the club’s history alongside George Best-Denis Law-Bobby Charlton and Dwight Yorke-Andy Cole. What marked them apart was the immediate understanding that brought so many gloriously interchanging moves and goals – particularly against Aston Villa and Middlesbrough – as well as a double of league and Champions League. Both Rooney and Tevez instinctively realised how they could work to maximise Ronaldo, and thereby the team. “I think he realised early on that I’m quite an unselfish player, that if he was in a better position I would give him the ball and that if he stayed up I would drop back to cover,” Rooney said two years ago. “We’d work for each other.”

It certainly worked perfectly for a season. Tevez of course took the first penalty in the Champions League final shoot-out against Chelsea and of course scored it. That continued a capacity for so many clutch moments, so many essential goals when no one else seemed capable of stepping up. West Ham saw it, United saw it, and City especially saw it in the 2011-12 title run-in.

Tevez had for two seasons been the lavish new project’s big signing and best player, before some doubt arose over whether he could play with Sergio Aguero and then that massive argument erupted with Mancini at Bayern Munich. Supposedly finished at the club, he returned after the supposedly fatal 1-0 defeat to Arsenal to immediately score four goals and re-ignite City’s challenge. One of his long-range goals in a hat-trick against Norwich City just encapsulated this rampaging abandon mixed with raw quality. This was his effect. This was the forward that Juventus had been waiting for since Alessandro Del Piero, and who took them up to another level to reach a Champions League final again in 2014-15. This was also exactly what Burdisso is talking about when he describes that extraordinary “capacity to decide games on his own”, “that force of will”, “that hunger”. There are few players like it.

“He was always a crack,” Schiavi adds, “always the difference.”

It was this that prompted Kia Joorabchian’s Media Sports Investment Limited (MSI) to invest in Tevez in 2004, with their financing of his $22m move from Boca to Corinthians then a record for a South American club, in a model now seen as the source of so many transfers – not to mention a two-year legal case that concluded with West Ham reaching an out-of-court settlement with Sheffield United over that 2006-07 relegation battle. Joorabchian has never been Tevez’s direct agent, but one figure who has worked closely with the player says: “Kia is the most important person in it all”.

Whatever the complex reality, the result has been a lot of highly lucrative moves, and accusations of the greed that has so irrevocably transformed the game. Tevez had been hugely popular at Old Trafford, but sources say Ferguson already had misgivings about his long-term commitment because of so much talk about wanting to soon return to Boca. United were going to offer him a contract with that in mind, only for the player’s camp to request Ronaldo money, and then getting it at City. A chant featuring the words ”that man we adore” was quickly changed to “money-grabbing”, and then a synonym for prostitute. An image was tarnished.

Juventus meanwhile reluctantly accepted that deep desire to return to Boca in 2015, only to be “amazed” when he moved to Shanghai Shenhua a year later.

It has all led to this conflict between the capacity to make a lot of money and wanting to be the people’s player, something that has been almost impossible to reconcile. Those who know him closely, however, say one is ultimately the source of the other since he is merely following the example of many South American players and looking to secure the future of his family.

“He has a lot of brothers and sisters, having been adopted by his aunt, and looks after all of them,” Simpson explains. “He’s bought them all houses, and he was always calling his brother, who still lived near Fuerte Apache.”

Tevez also set up a foundation that works in the area, and Simpson finds it difficult to square the perception of greed with what he knew of the player, and the man who invited him to Christmas dinner in 2006. There was a complete absence of bling, hence the story of the Hublot watch.

Tevez doesn’t actually wear a watch at all, and had never even worn a suit until Alan Curbishley introduced them for West Ham. “What’s this?” he laughed with Mascherano, before turning up in an oversized baggy two-piece the next day it was required. Tevez also became a fan of golf, but didn’t play with teammates at any of the lucrative clubs around where he lived. He would instead just type “golf” into his Satnav and go where it took him, usually a municipal club that then attracted a lot of onlookers.

“He wasn’t materialistic at all,” Simpson says. “That’s why he looked even more alien in the suit, as it went against the person he was. He was very much a family man, didn’t go out, went to the gaucho grill for dinner and was very happy in his little life. He’d just put his Cumbia music on in the car and, if you didn’t speak, he wouldn’t say anything – maybe for a whole trip – but he would laugh a lot.”

This was also the source of what Michael Carrick has described as the “strangest friendship in the world” with Patrice Evra and Park Ji-Sung at Old Trafford, which involved so much “smiling and laughing” even though they barely spoke the same language. It suited Tevez not to be able to fully communicate with them because he “doesn’t necessarily want to get into conversations”.

And after all that, even the conversation around him in Buenos Aires now is somewhat different, somewhat complicated.

There is a large portion of the population who will always love him because of his background, who will always see him as the people’s player, but a series of stories have changed the minds of others. There was first of all the 2015 challenge on Ham that left the player out for almost two years, the transfer to China after the supposedly final homecoming, and most recently the “friendship” with former Boca chairman and polarising current Argentine president, Mauricio Macri.

It was this that led to that criticism from his idol.

“I see him as very Macrista, which is stupid of Carlitos,” Maradona said in August. “If he is a Macrista, he is no longer the player of the people.

“If he tells me he is the same, the lad I know, I will continue supporting him, like I always have… I have to talk with him.”

The situation has led to River fans openly taunting Tevez about it, and will likely involve his own words that “there’s more to life than money” thrown back at him at the Monumental on Saturday. Again, those that know him would say it’s more complicated, that the relationship with Macri is just from the time at Boca. It’s just it’s a bit rich given the economic turmoil of the country.

Whatever about the people’s player, though, Tevez remains a team player. And now a leader. He invited the entire Boca squad around to his house for a big meal on Wednesday night. He wanted to foster a greater spirit ahead of Saturday: the match which will mean more to Boca than any in their history, and which will mean more to him than any in his career.

When he was asked about a lot of the commotion surrounding him for this game, Tevez was heard saying: “This final is about the glory of the club, it’s not about me.”

There lies a defiance, and difference of perception, that has defined a career.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments