Poor Gazza says he’s a sad drunk – I prefer to remember the football genius who lit up the world

He has spent the last decade in an endless round of therapy, addiction and loneliness, all his money snaffled by advisers and hangers-on, says Jim White. His appearance on a podcast this week was a hard listen, and a lesson in the destructive force of fame

Poor old Gazza. Hearing him talk this week on some podcast about how he used to be a happy drunk but now he’s a sad drunk and about how he lives in his agent’s spare room, seeing the footage of him, his face ravaged by self-loathing surgical procedures, there can be no other reaction: poor old Gazza, how did it come to this?

Pretty simple really. Fame did it to him, lanced him through the soul. Ill-equipped to handle it from the start, he has been chewed up and spat out by celebrity.

And now, a couple of generations on from his heyday as Paul Gascoigne, the man whose footballing talent once electrified a nation, this is what he is known as: a victim. That is the only currency he has left to trade in.

Looking at him as he talked with Jake Humphreys on The High Performance podcast, it was impossible to reconcile his present with his past. Where his old England mate Gary Lineker looks magnificent in his sixties, Gazza is a husk. Yet 34 years ago he was the single most dynamic sportsman in the country, a footballer of panache and swagger, an extrovert seemingly unencumbered by restraint. On the pitch he was gloriously uninhibited, off it he was uncontrolled. He fulfilled every laddish ambition, delivering in his day job while lording it in his spare time.

And the unintended consequence of his arrival in the national consciousness was that his timing was both perfect and at the same time horribly self-destructive. Perfect, because he came to prominence just as football was re-emerging from its 1980s death spiral.

What the 1990 World Cup – that summer of Des and Pavarotti and Gazza – did was remind us of the game’s power. For those about to exploit new broadcasting technology, Gazza was revelatory. He made them appreciate that football was ideal digital content: it is no exaggeration to suggest the Premier League was born of his popularity.

At the same time, Rupert Murdoch, the man exploiting the game’s televisual pull, was also in control of our tabloid press. To encourage us to buy his new satellite dish product, he cleared space in his papers, used their editorial as advertising. Football became front page as well as back page news. Murdoch’s publishing and broadcasting rivals had to match him. And Gazza, naive, hapless, accident-prone as he was, provided endless copy for them all.

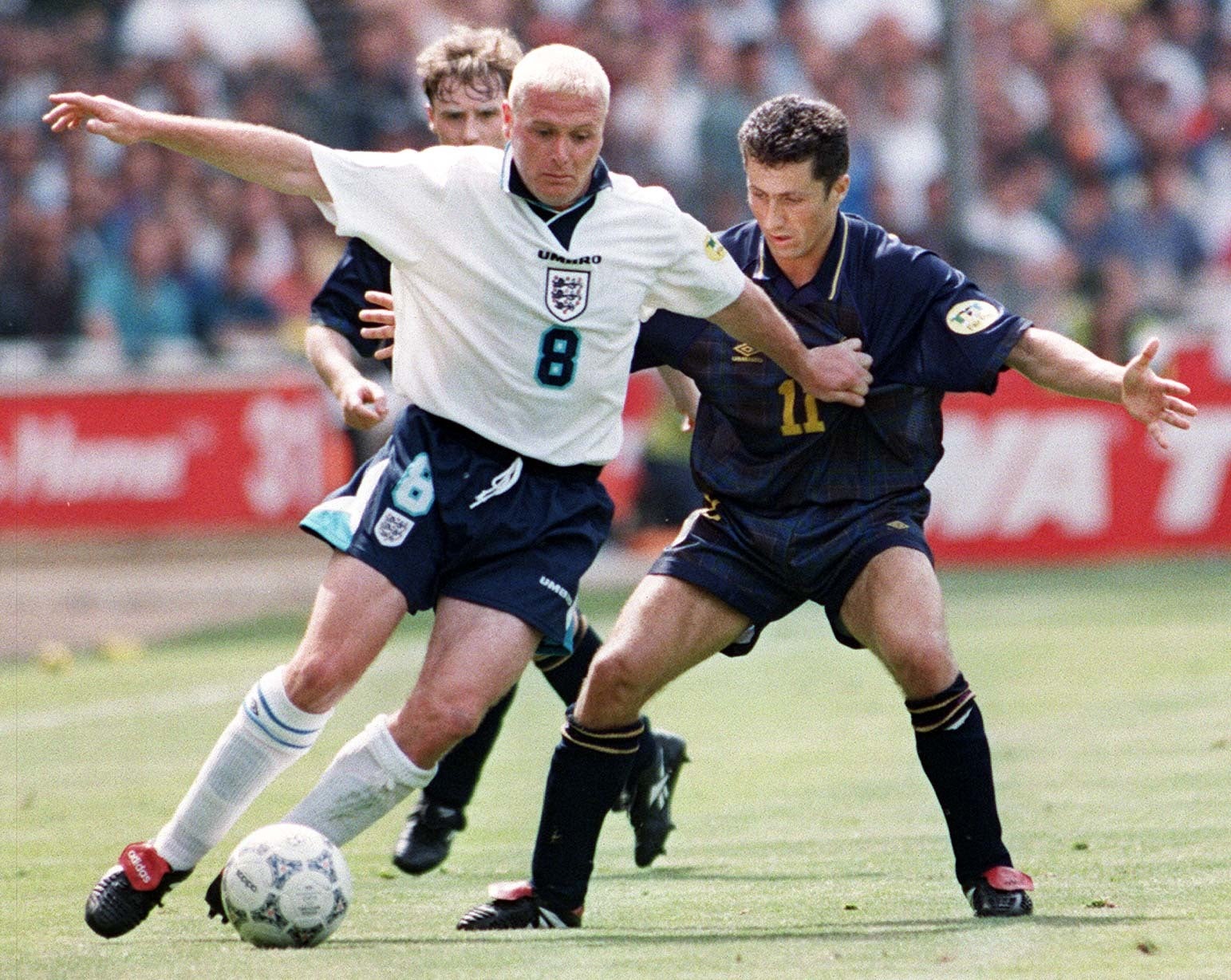

Euro 96 was his defining moment. Before the competition he got publicly plastered in Hong Kong, gifting his critics a chorus of harrumphing and moralising. Then, when things got underway, his brilliance drove the England team forward, he scored a wonder goal and celebrated by taking the mickey. The same outlets that had fulminated could eulogise. That was Gazza: he was an endless stream of material, good, bad and, in the case of his treatment of his wife, ugly.

But while others, like Lineker, could cope with all the attention, Gazza was consumed by it. He needed it, but it hurt him. He sought it, but it damaged him. Even as his footballing prowess inevitably diminished, his celebrity remained. He became a soap opera, with storylines about his marriage break-up, domestic abuse or bringing a takeaway chicken to a man on the run.

His approach to finance had never been exactly astute, and when the big earnings that had once maintained an entourage of hangers-on disappeared, there was nothing to replace it. He tried to be a team manager, but he was hopeless. His punditry was rambling and incoherent. It soon became evident that the only thing he could do to make money was talk about himself.

Then there was the phone hacking, which tipped him into serious mental deterioration. Between 2002 and 2004, convinced he was being spied upon, he changed his phone 60 times. He fell out with his family, certain they were the source of tabloid stories.

When he checked into the Priory for therapy, he refused to open up to his fellow patients in group sessions convinced they would flog his revelations. Fear degenerated into paranoia. He was all over the place. And what did his hackers, the Mirror Group, gain from driving him to despair? Just 15 articles.

About 10 years ago, when he was trying to recover his financial wherewithal by doing a public speaking tour, I interviewed him. The poor bloke was a jittery mass of ticks and shakes. The thing I noticed most about him was his fingers.

It was not just that his nails were chewed beyond the quick, the flesh around them had been bitten almost to the bone. A mass of cuts and scabs that he picked at constantly as he spoke, it looked as though he had filed his fingertips with a cheese grater. This was a bundle of nerves. This was not someone remotely equipped for the limelight.

He has spent the last decade in an endless round of therapy, addiction and loneliness. All his money has long gone, snaffled by advisers and hangers-on, large amounts given away to charity.

For the modern world that doesn’t remember him doing those astonishing, uplifting, glorious things on a football pitch, what they know is someone famous for being horribly damaged by fame. And as was proven by his appearance on that podcast this week, there are still plenty willing to wallow in the vicarious thrill of proximity to his misery. Poor old Gazza indeed.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments