Why lump it long is long gone in the Championship

The race for promotion has been characterised by teams playing open, attacking football because it creates a model for long- not short-term success

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

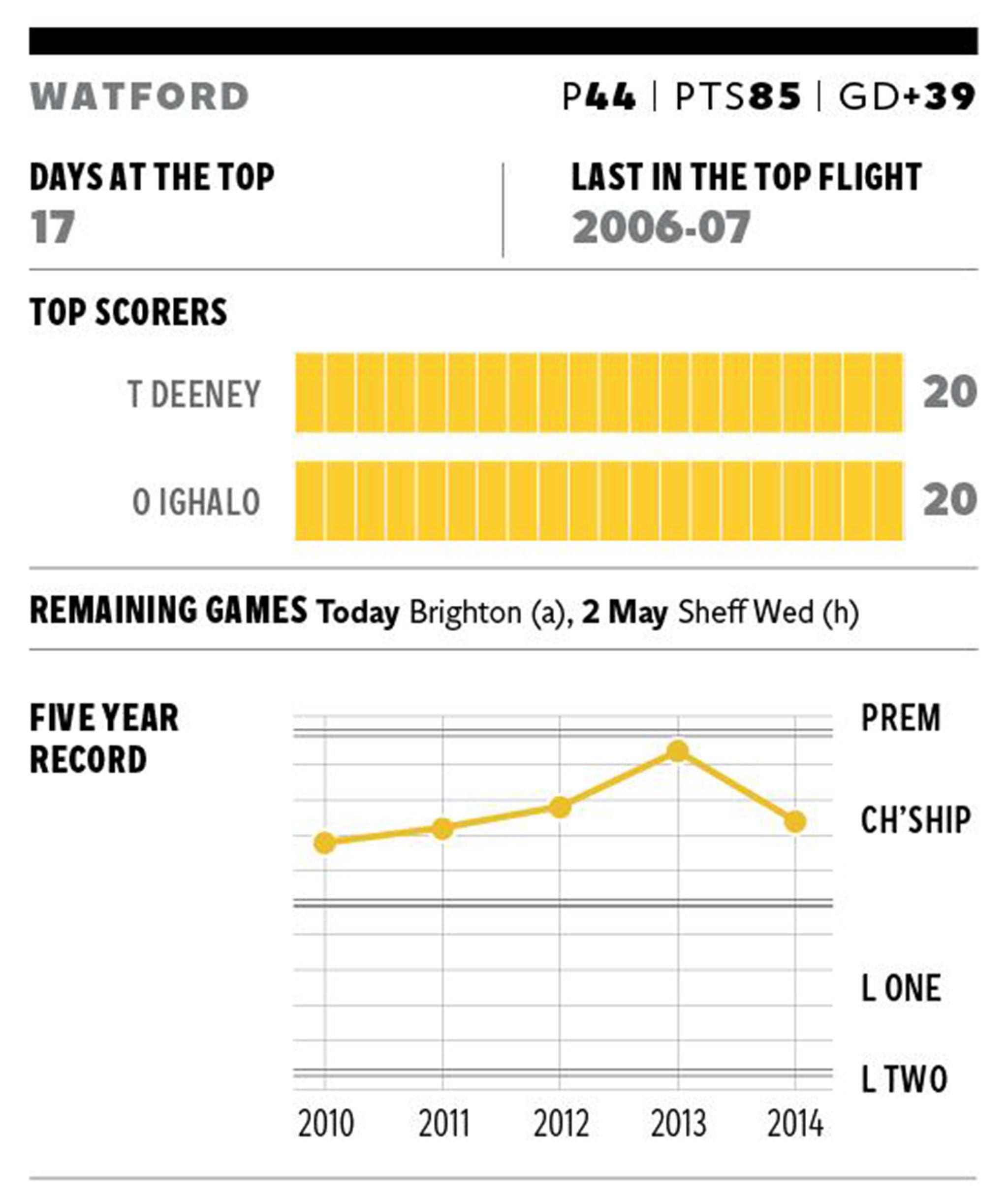

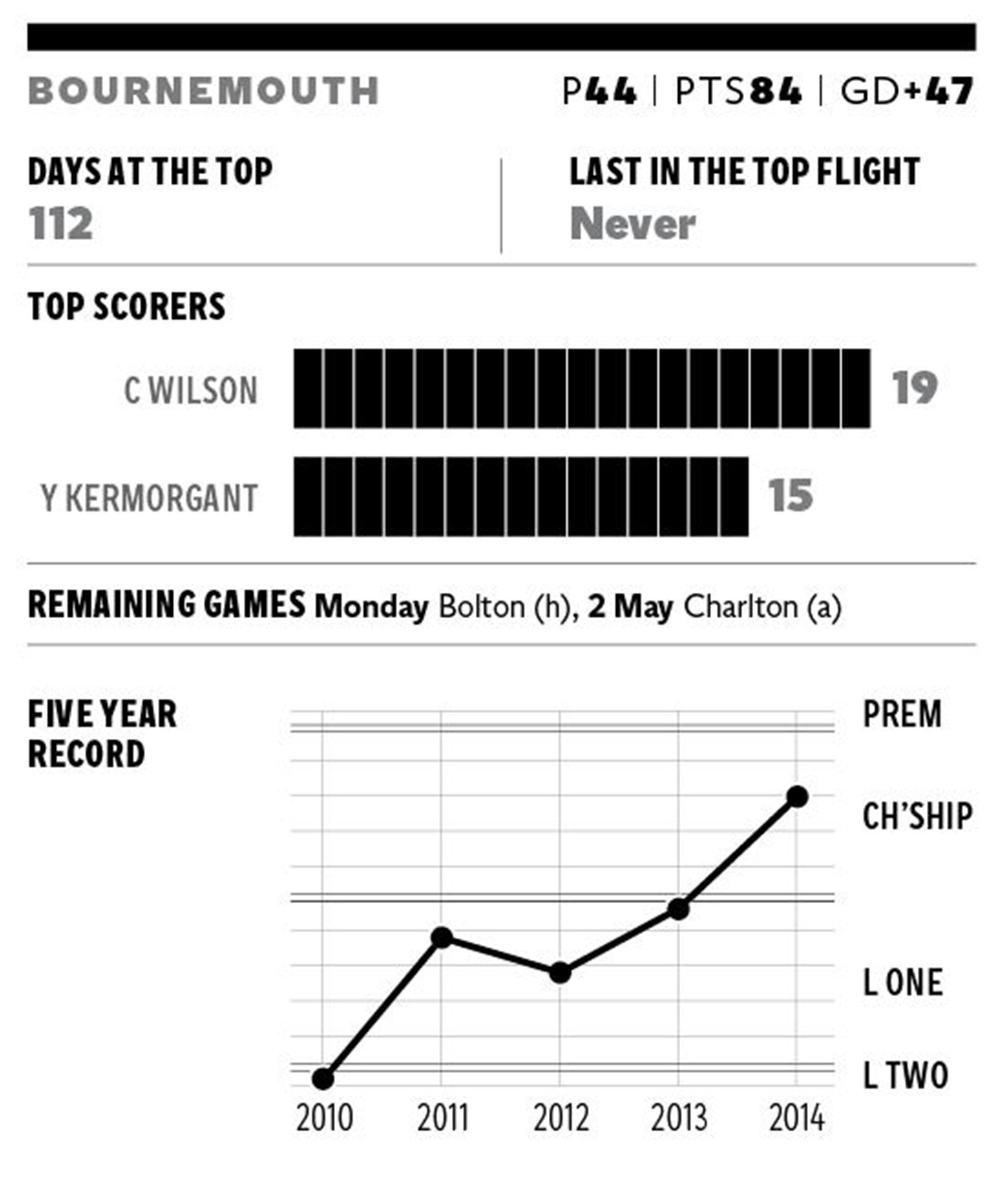

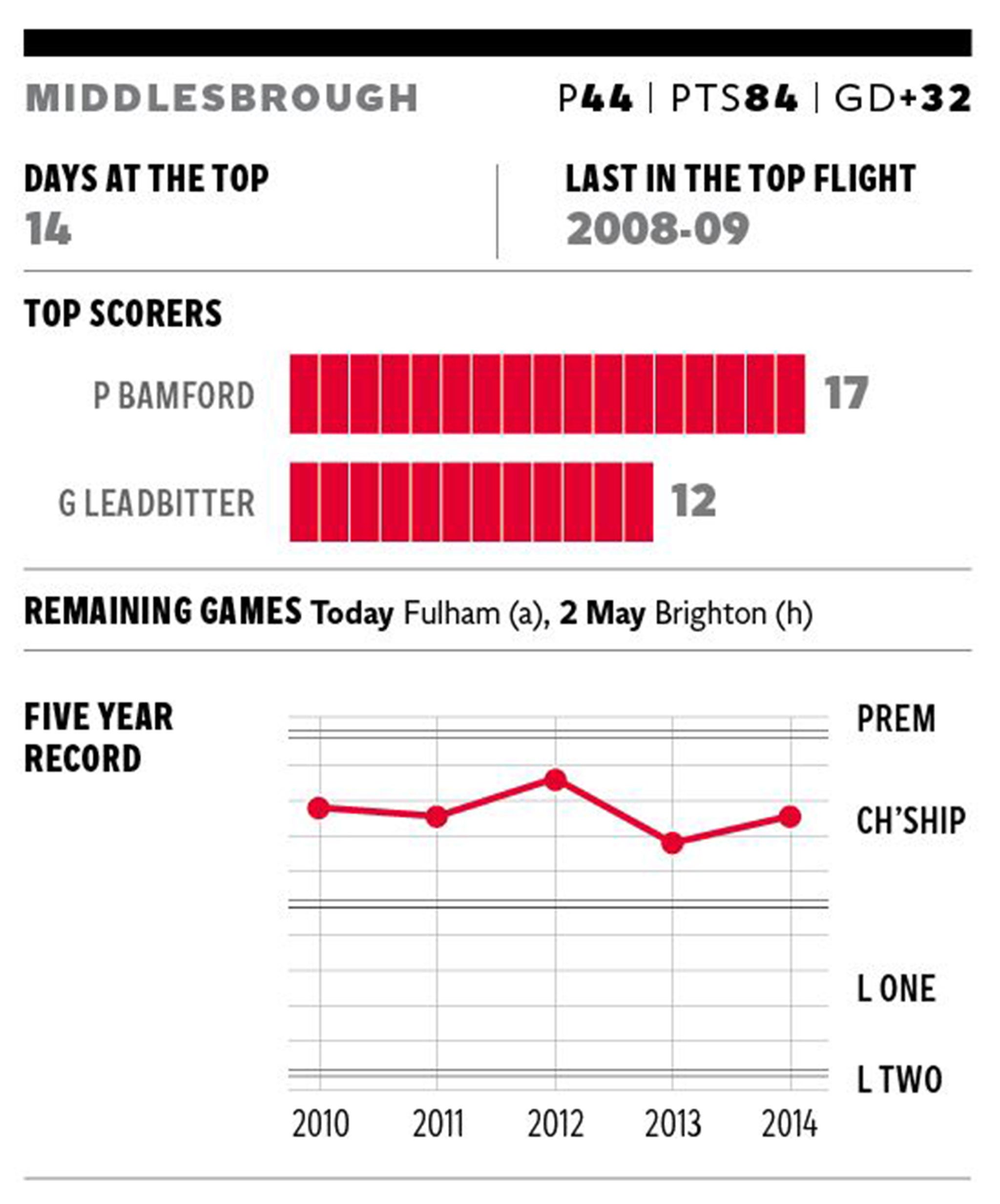

Your support makes all the difference.Four teams, separated by three points, playing for two places, with two games left. Beneath them, another four teams, separated by four points, trying to squeeze into the last two play-off spots.

This has been a remarkable Championship season and the final two rounds of fixtures will provide the perfect conclusion. It has been gripping not just for the tension, the unpredictability, the fine-margin drama – such as Bournemouth’s 2-2 draw with Sheffield Wednesday last weekend – but also for the quality of the football.

If the Championship always used to be a mad scramble, a desperate pub car-park scrap to find a way into the light, this year is different. The top eight in the division – with only one or two minor exceptions – are trying to shoot their way into the Premier League, playing open, expansive football of the type that has only fleetingly been seen in the division before.

There have, of course, been excellent attacking teams in the second tier. Kevin Keegan’s famous Manchester City side of 2001-02, built around Ali Benarbia and Eyal Berkovic, set the modern standard, scoring 108 goals on their way back up to the Premier League after a long absence. Steve Coppell’s Reading team scored 99 in 2005-06 while Harry Redknapp’s Portsmouth managed 97 three years before.

Rarely before, though, have there been as many good sides with the same commitment to attractive, assertive, front-foot football. Four teams – Bournemouth, Watford, Norwich City and Derby County – have scored more than 80 league goals, the first time that has happened since 2002-03.

If Watford score just two more in their final two matches, then Slavisa Jokanovic’s side will join Eddie Howe’s beyond 90. The last time two second-tier sides cleared that marker was 1963-64, in the form of Southampton and Rotherham.

There has, clearly, been a change of emphasis recently, a realisation that the best way to escape into the Premier League – and to stay there – is with an open game.

“Everyone wants to play open and attractive football,” Leroy Rosenior of BBC’s Football League Show told The Independent this week. “It has made for the best Championship in years, and one of the most entertaining ones.

“All the sides in that top eight, they want to play front-foot, high-pressing, high-energy, passing football. They make the pitch nice and big and try to create opportunities. Ipswich are maybe a bit more defensive-minded and, with the resources they have got, you can understand that. But all the other sides in that top eight want to play attacking football.”

Don Goodman, the former Wolves striker who covers Championship matches for Sky Sports, agrees entirely. “As a nation we are changing and embracing a more expansive brand of football,” he told The Independent. “All of the top eight have been committed to playing a good brand of football. In the past there has been an assumption here about a way to get out of the Championship, but I think that has changed. We are open to a different way.”

While there are more and more imported players in the Championship, the impressive thing about the quality at the top end this year has been its Britishness. Of the top eight sides, six have British coaches, and Rosenior says that the days of British managers hitting diagonal balls and digging in have long gone.

“There was a time when British managers were seen as just wanting to play long ball all the time,” Rosenior said. “That came from Charles Hughes, the old Football Association director of coaching, where you just play long balls and play the percentages. But we are now developing a younger, more progressive style of coach, who want to play and express themselves. Look at Steve McClaren, Mark Warburton, Eddie Howe and Alex Neil.”

This change of approach is not just aesthetic – although it certainly does appeal to fans – but also pragmatic. Teams, not just in the Championship but also in League One, want a stable, sustainable and appealing way to move through the divisions and they look, naturally, to the example of Swansea City. While Swansea have changed managers over the years, they have maintained the same philosophy and many of the same players, and are now an established mid-table Premier League team.

“Norwich City and Southampton won consecutive promotions, from League One to the Premier League, recently, and did so playing good football,” Goodman said. “Swansea City came up through the league playing the same way, and even kept some of the same players now that they had in League One and League Two. You can see from Brentford and Wolves, who came up last year, that they have played football in the Championship and more than held their own.”

It is no secret that much of what has happened at Bournemouth recently has been modelled on Swansea, and in Eddie Howe they have a trusted coach with a similar philosophy. Goodman tells the story of how Ian Holloway spent time at Swansea after his defensive-minded Leicester City side were relegated from the Championship in 2008, which changed his philosophy and inspired one of the other great success stories of recent years.

“Ian spent quite a bit of time at Swansea and watched how they did things there,” Goodman said. “And so when he got a new job he would try to outscore the opposition. There began the Blackpool story – what he did there, and the brand of football they played, was remarkable. When they were in the Premier League they were everybody’s favourite team. They got relegated with 39 points. There are teams down there now who would rip your arm off for that.”

What Blackpool – despite relegation – and Swansea have shown in the top flight is that a balance between efficiency and aesthetics is a false dichotomy. Expansive, attacking football can be the best approach for a promoted side with limited resources. Building a settled, cohesive, coherent side should be the starting point, rather than a short-termist push for promotion by any means available.

“If you want to stay in the higher echelons of the game,” said Rosenior, “you need to play a certain type of football, a certain type of player. Swansea are a good example. If you stay in the Premier League you need quality, and you need to be able to play a bit when you do have the ball. Swansea are a great example, from the [Roberto] Martinez era to the present day. Players are attracted to it. That is why the club has developed, it is a really good model.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments