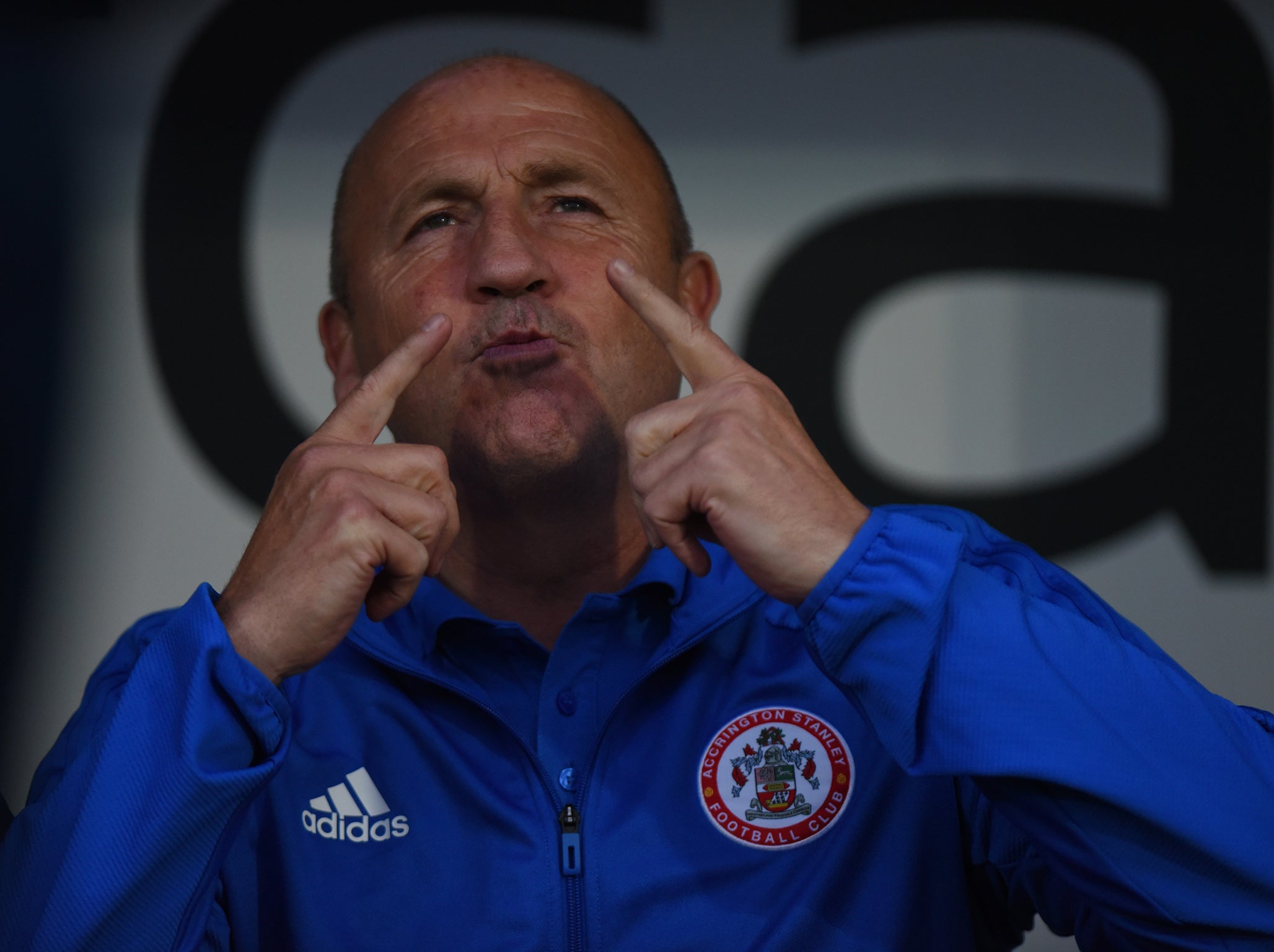

The modern miracle of Accrington Stanley: Title contenders with the joint lowest budget in the league

A modern miracle is happening at the Wham Stadium. The club with the joint lowest budget in League Two will go top on Saturday if they win at title hopefuls Luton

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Jimmy Bell tells a sort of funny story about the routine at Accrington Stanley, one that involves him having to bend facts when signing players from higher levels. It was last winter when two loanees came in from Hull City, then a Premier League club. “Where do we train,” one of them asked, to which the assistant manager answered, “just meet at the ground and we’ll go from there.”

In truth, Accrington do not have a training facility. They rent a 3G pitch at the Hyndburn Academy, from where they get turfed out prompt at midday every day. The squad then return to the modest surroundings of the Wham Stadium, where they have their lunch. Bell and John Coleman, the club’s manager, realise that sometimes it is better to hide realities about life in League Two until contracts are signed.

“We do our homework on players and we think we have solid judgement when it comes to character so we trust they’ll just get on with it,” Coleman admits. On this occasion, he was certainly right: one of the Hull loanees, Harvey Rodgers, is now at Accrington on a permanent basis.

This is the club that has the joint lowest budget in League Two beside regional rivals, Morecambe. On Saturday, Accrington have the chance to go top with a victory at Luton Town – the team they are trying to catch, which also happens to be the team with the supposed highest budget.

If Accrington were to win the league, it would be a modern miracle in a financial sense. Yet Coleman being the way he is did not make survival the target at the start of the season like many facing his economic challenges probably would. He had missed out on automatic promotion in 2016 when on the final day, Accrington could only draw with Stevenage. From that experience, he draws strength rather than doubt; that surely it can be done.

Last summer, he had lost three of his key players, all of them to clubs in higher divisions – which marks Coleman out as a developer of individual talent as well as a developer of teams. Goalscorer Shay McCartan moved to Bradford City, player of the year and defensive rock Matty Pearson went to Barnsley and Omar Beckles signed for Shrewsbury Town. The summer before he had lost Josh Windass and Matty Crooks to Glasgow Rangers and the campaign that followed started badly to the extent it ultimately cost Accrington a place in the play-offs. This time, he was better prepared having anticipated departures and signed replacements first.

“I sat everyone down before pre-season, including the kit man, the chief executive and quite a lot of people involved outside the football operation, and said, ‘I really believe we can achieve promotion automatically and we’ve all got to buy into that together.’ I come from a background where you have to scrap for everything. Though money makes success easier to find, it doesn’t always lead you to where you want to be.”

Coleman and Bell are full of stories, actually, and that is because their association together goes back so far, all the way to Liverpool’s Sunday leagues as teenagers. They describe each other as “best mates,” rather than manager and assistant and they believe they are fortunate, such is the transience in relationships elsewhere in professional football.

When you find out that Coleman’s connection with Paul Cook goes back even further and then look towards the top of the League One table, it reveals that two of the most competitive managers outside the Premier League and the Championship have shared similar paths, albeit with one key difference.

In 1974, Leighton Baines’s grandfather, Dixie, managed a junior side from Kirkby called St. Joseph’s. In that side was an eleven-year-old Coleman and a seven-year-old Cook. It did not matter that Cook was so much younger than the other lads because technically and mentally, he was already there.

While Cook would embark on a professional career as an industrious yet stylish left-footed midfielder, representing a host of north west clubs, Coleman – the leading scorer at St Joseph’s – would take a scenic route to the Football League, arriving as a manager in 2006 following promotion from the Conference with Accrington. To get to Accrington, Coleman had played for Kirkby Town, Burscough, Marine, Southport, Runcorn, Macclesfield, Rhyl, Witton Albion, Morecambe, Lancaster City and Ashton United.

Cook is now in charge of one of his former clubs, Wigan Athletic. Last month, he took on the force that is Manchester City and won. For those that know Cook the most, the sight of him fully-flushed and jabbing a finger at Pep Guardiola was no surprise.

“Typical Cooky,” Coleman told The Independent this week, though he was keen to emphasise it is too easy for managers to become characterised through their most dramatic moments. When Giorgio Chiellini shows that fire lies beneath like he did starring for Juventus against Tottenham on Wednesday, it is described as refreshing to see. When a lower league manager does it, it explains why he is there.

“Yes, we’re passionate but I think we’re both knowledgeable about football and decent judges of situations,” Coleman says. “You can’t get along on passion alone.”

At the end of his playing days, Cook had signed for Coleman at Accrington. Cook would then start his managing career at Southport where he was sacked - a fate also met later by Coleman, though he claims he was ready to walk out anyway when, having saved the club from certain relegation, he was condemned for his ‘style of touchline behaviour’ in a statement that would win awards for snobbery.

Cook relaunched his managerial career at Accrington after a successful spell at Sligo (Coleman managed there as well after leaving Southport) before establishing himself at Chesterfield and Portsmouth ahead of his arrival at Wigan last summer.

Coleman, meanwhile, went back to Accrington for a second time following Cook’s exit and a period of struggle under James Beattie. In total, with a two-year gap in the middle having initially left for Rochdale where he could “not spot the cracks,” in the same way he could having been so familiar with the challenges at Accrington, his association with the club spans nearly seventeen years.

Coleman says it is important for Lancashire that football rediscovers itself. This season, as well as Accrington and indeed Wigan, Burnley, Blackburn, Blackpool and Preston North End are surpassing expectations. Yet it is probably at Accrington, the ultimate minnow club, where the greatest achievement might happen if promotion into the third tier is secured for the first time.

“I’m not one of these that say, ‘Don’t mention the P-word.’ Coleman insists. “I want to think about promotion every day and speak about it every day. It has to act as a motivation and drive you. It has to be an obsession. If I wasn’t obsessed, I wouldn’t be here.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments