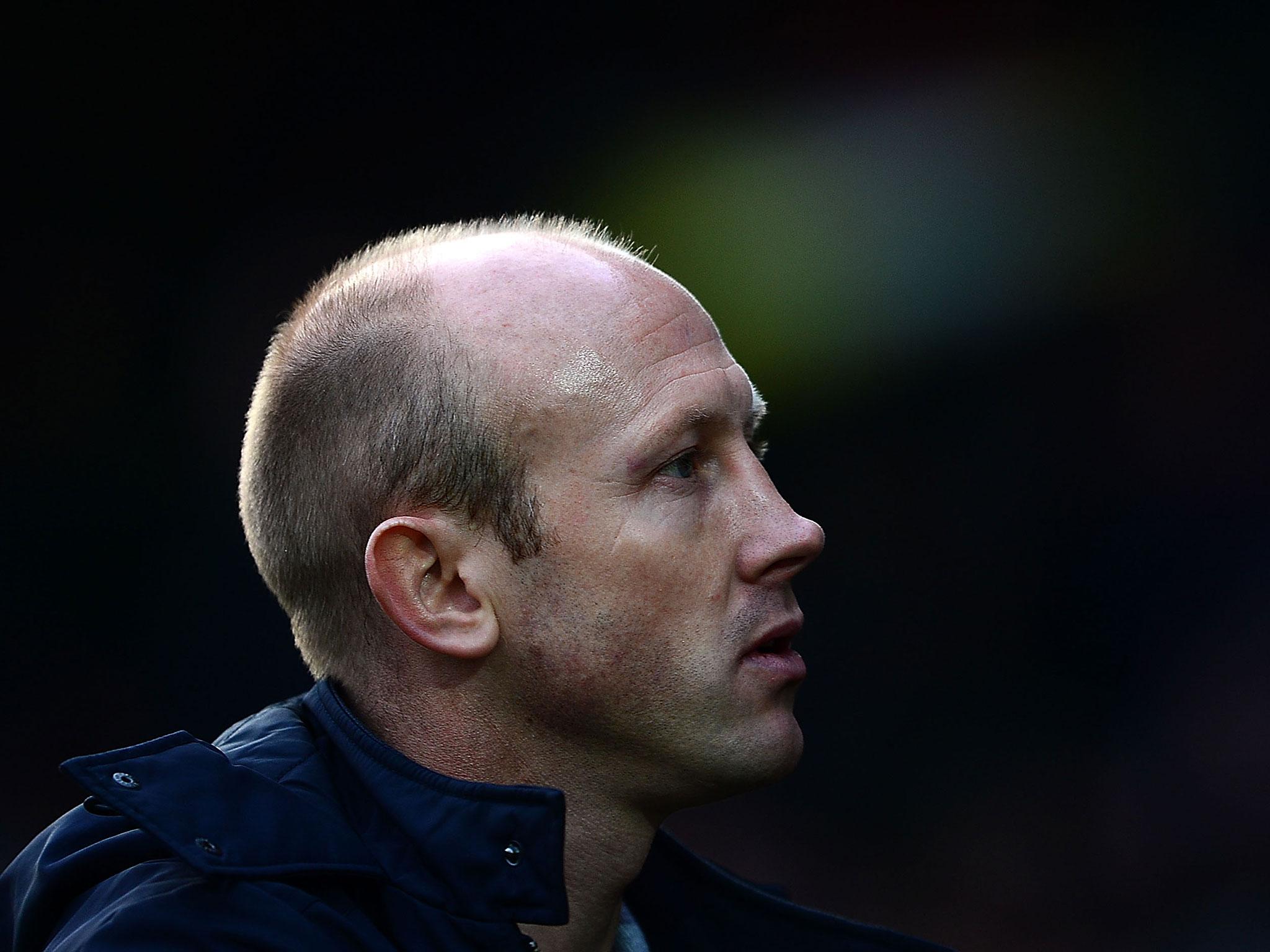

Darren Way: A man driven by detailed obsession after his brush with death

Interview: The Yeovil Town manager talks to The Independent about the car crash which almost claimed his life and how it transformed his perspective on everything

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When Darren Way was a player he used to tackle side-on, which is not allowed now, but it was his way of protecting himself. It kept him from snapping a cruciate and then, in 2008, it kept him alive too.

Way had just re-joined Yeovil Town from Swansea City and was moving his things back. He was in the passenger seat and saw another car coming straight at him. So he treated it like a tackle, turning in his seat, locking his legs, bracing his right hand against the dashboard, as the two cars met at a combined 140mph.

“That kept me in the world. Just because I braced myself. Everything locked, everything shattered, everything came out of its joints.”

Without this instinct for self-protection, Way would have died. Even with it, he nearly did. Trapped in his seat, he managed to tell a passer-by to tell his wife and children that he loved them. The easiest option was to shut down, to close his eyes and go, but the stranger kept him thinking about his family, which in turn kept him from giving up.

It took 50 minutes to get Way out of the mangled car before he was airlifted to hospital. He stayed there for 12 weeks. It took him eight months to walk again.

“All I had was this,” he says now, raising his left hand proudly in the air. “Everything else was smashed up. Right hand, fracture, dislocation. Right wrist, fracture, dislocation. Right elbow, fracture, dislocation, and right hip. Fractured patella, both sides. Fractured kneecaps, everything.”

It was a trauma that would change anyone’s life. Many men, with two young children, and a compensation pay-out, would retreat into family life after coming so close to death. But Way did not. His football career was over, but his desire to work hard and make a difference was stronger than ever.

“It made me more resilient,” he says. “You don’t realise how lucky you are to stand up straight, when we finish this interview. That is the most daunting feeling, to not be allowed to walk.

“And it’s made me more obsessive. And I was obsessive before. I know what that feeling is like, not to have any legs, and to lie in bed all day. I’m even more determined to be upright, going about and affecting the world.”

During an hour-long talk at Huish Park, in the long build-up to Manchester United’s FA Cup visit there, Way keeps coming back to obsession. He has always been intense and driven – one former team-mate describes him as a “tenacious little fucker” – but now he is a manager he is utterly consumed by his work, by Yeovil Town, and by management as a trade.

So for all the obvious differences between managing towards the bottom of League Two and at the top of the Premier League, Way is obsessed by Jose Mourinho, Pep Guardiola, Jurgen Klopp, Antonio Conte, and how they all work. His office is full of books on elite players and managers – he is currently reading ‘Winners’ by Alastair Campbell – and every time another manager comes on the television, Way has his own observation about how they work, proud of the fact that they are all part of the same game.

“Every manager, in every boardroom, is trying to create one thing, and that is momentum. Mourinho will walk round the building and he’s trying to generate momentum. Klopp is trying to carry the history of the club to create momentum there.”

Most of all, Way is obsessed with what he calls ‘the system’, namely the rules about signing players that make it so difficult to be a League Two club. Since the start of last season, loans can only be agreed during the transfer windows, rather than on a more immediate ‘emergency’ basis. For a club like Yeovil, which depends on loans, this makes life very difficult, not least because loanees can still be recalled by their parent clubs. The system, as Way keeps saying, is “killing” his club.

That is why Way’s job is so difficult, trying to build a stable squad with one of the smallest budgets in League Two, just £1m. The richest teams in the division spend £2.5m, but Yeovil’s budget should be more like £1.3m just to give themselves a chance. Even then relegation rivals like Chesterfield or Forest Green Rovers are thought to spend more than £1.5m each year. At the start of this season, Yeovil only had three players secured to contracts. Even on the Wednesday before they beat Bradford in the second round of the FA Cup, they only had 10 players in the squad.

Way’s job, or one of his many jobs, is to find enough free transfers and loans who the club could afford, who would help keep his team in League Two, and who were happy to move to Somerset. “I’ve got no chief scout, no head of recruitment, no chief executive,” Way says. “It’s just me and the chairman doing 1,000 jobs, every minute of every day.”

But even playing the loan market is stacked against a club like Yeovil now. The players he brings in on loan are not always cut out for the realities of a League Two relegation scrap, especially when they drive down to Huish Park in cars that cost £90,000. And even when he does find someone perfect, there is no guarantee of keeping hold of him.

Even now Way is still exasperated about what happened in the January window last year, when his best player Ryan Hedges was recalled on 31 January by parent club Swansea City so he could be sold to Barnsley. Way was trying to find a replacement while managing a game against Plymouth Argyle, and was turned down at 10pm. With Hedges, Way felt his team could have reached the play-offs. Without him, they won two more games all season. “Whoever decided to put that in place?”

The comparisons with Mourinho, Manchester United and Alexis Sanchez do not even need to be made. Way has never paid a transfer fee for a player and of the two strikers he is looking to buy this month, one has already been at Yeovil on loan and the other plays in Step 3 of non-league.

Yeovil, ultimately, are paying the price for over-extending themselves when they made it up to the Championship, for the first time in their history, in 2013-14. They have been belt-tightening ever since and were it not for the money earned when they hosted Manchester United in this cup in 2015, they would have been in serious trouble. “I felt the decision-making perhaps from the Championship to League Two could have been better, if I’m honest,” admits Way, although he does not want to blame the owner. “Now it’s trying to gain that momentum and get back to where I think the club should be. And that’s competing at the top end of League Two.”

So how does Way try to get them there, with no money to spend? With hard work and force of personality. He gets in at 6.15am, his small but loyal staff report at 7.30am and they start to plan the day, and how to stretch their squad across the busiest season in Yeovil’s history. Way has plastered the ground with motivational mottos, Connor McGregor quotes, pictures of lions, A4 printouts of Wembley Stadium and a thin line of green tape to show his players the margin between success and failure. There is a new slogan taped to the dressing room floor for every game, last week it was ‘MENTAL TOUGHNESS’. Every player has a ‘Warrior Card’ in his dressing room locker with his own personal goals written on it.

But underneath all of this there is something of the martinet about Way: his attention to detail, his directness, the demands that he makes, almost courting unpopularity. “People are not going to like me in this building. They hate me, at times, because of my standards. But you’ve got to work.” He gets animated. “Write down on a bit of paper what you’ve done today. People go to work, but if you ask them to write down on a bit of paper what they’ve done, the paper’s not even filled! It’s more about I’ve got to go and get a coffee.”

It is an uncompromising approach but the evidence is that it is working. Yeovil are still afloat, thanks in part to this lucrative cup run, and still in the Football League, just. They are two places and two points ahead of the relegation zone and that is the only thing that matters. Being in the spotlight is nice, but not at the cost of safety and survival.

Way admits that relegation to the National League would be “devastating” for Yeovil, but insists that it has “not even crossed [his] mind”. “I’ve had that pressure now for the last two-and-a-half years, and I’ve delivered.” Blunt, yes, but you cannot single-handedly keep a penniless club in the Football League and be diffident or ironic about it.

So when he reels off a list of what he has achieved here, by simply keeping the ship afloat, you wonder whether someone less obsessive could have done the same. “Success to me is: 1) Balance the books, which I’ve done every year. 2) Finish a league position higher. 3) Keep the club in the football league. 4) Score more goals every year because we’ll be more attractive. And have a cup run. I’ve ticked all those boxes.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments