How Portugal became European football’s coaching production line

Despite not having a rich coaching history, Portugal currently provides more non-domestic managers to Europe’s top five leagues than any other country

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When you look at the Portuguese Primeira Liga, it’s impossible not to be drawn to the big clubs like Benfica and Porto that have dominated for so long, but there’s something underneath that has now driven the wider game just as much.

You might also be watching football’s coaching future, and maybe your own club’s next manager. The competition has become a breeding ground for the game’s thinkers. Portugal currently provides more non-domestic managers to Europe’s top five leagues than any other country. They are the best represented in the Premier League outside the English, and the best represented in Ligue 1 outside the French. They are also the reigning European champions, with the country’s victory at Euro 2016 under Fernando Santos also representing a victory for a way of playing.

Portuguese managers have not just won the biggest trophies, but influenced the way the game is trained, especially in relation to concepts like periodisation.

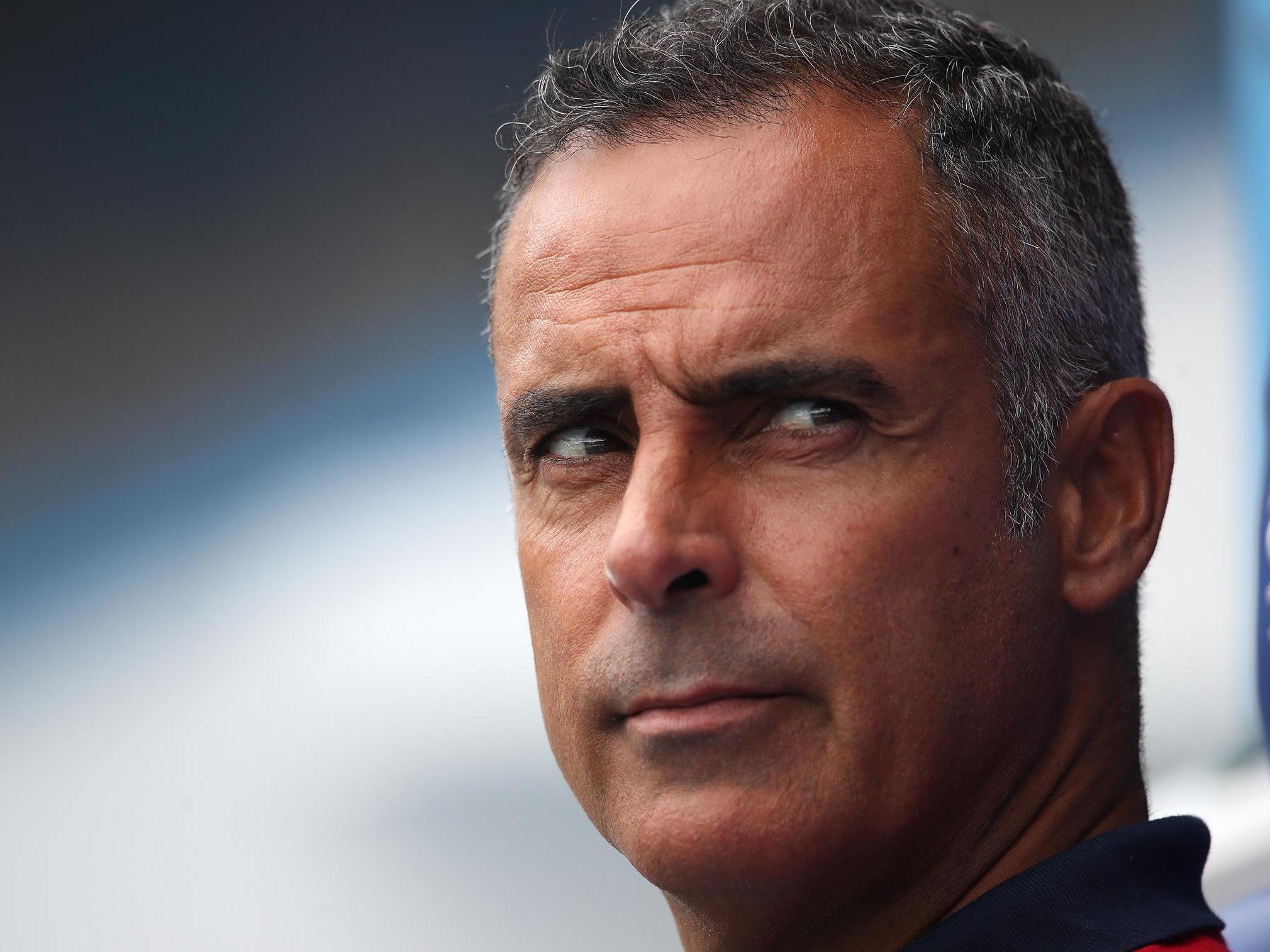

That was an era famously kick-started by Jose Mourinho, but continued by coaches like Jose Gomes, with significant evolution along the way. Gomes is now preparing Maritimo to get back playing on Wednesday, but has the suitably international career you’d expect. The 49-year-old was in charge of Reading last season, having previously worked in Hungary, Saudi Arabia and UAE.

Gomes says he has spent a lot of lockdown studying opposition and thinking about how to play, and believes it’s that – thinking your way through complicated problems – that has played a large part in his country’s rise as a production line for coaches, especially given Portugal’s previous relative poverty.

“You only have to look at the way we develop as coaches,” Gomes says. “At the start, we are working in very poor conditions, not very good facilities. When I started, for example, I had to share a pitch with two more teams so we had 25 players training in one third of a pitch. You must prepare your game in that space – with simple things missing. So we must try and find new ways of working regarding football issues.

“Things are better now, and we have improved a lot, but I think sometimes we make miracles given the conditions we have and the number of people [10m] in the country.”

That history of adaptation, however, has since been complemented and legitimised by a culture of education. Portugal is one of those countries – like Italy – that has made coaching an academic vocation.

“I studied football in university,” Gomes says. “We do have different routes. I played football, until the third division. I was a bad footballer! So it’s not enough to receive the knowledge. I studied. This also happened with Mourinho, Andre Villas-Boas, although to a different university. So we study football in university, and after we finish the degree, we learn the professional life and reality by being part of a club staff. That’s what happened with me. If you were a professional footballer, you still must go to the Portuguese federation and do the normal coaching courses. So we drink water from the same source.”

This raises a question that leads to a little bit of debate. Does Portuguese coaching have a defined style? It’s difficult not to associate it with the more controlled defensive organisation applied by Mourinho, and then Santos at Euro 2016.

Gomes disputes some of this.

“Thirty years ago, while Benfica and FC Porto did well in Europe, our national team always had problems qualifying for the European Championship or World Cup, due to the difference of physical capacity. It was incredible because we always had very good players able to dribble and do fantastic things with the ball, but would struggle against England or Holland or Germany. So basically we defended at that time, as they were stronger than us.

“Step by step, that has changed. All the clubs are working very well, the knowledge about training is the same in most of the world, and the thing that really makes a difference is how you think about the game, how you prepare. Portuguese managers now adapt so well. We’ve shown this in Italy, France, England… ‘But I don’t think it’s a defensive school. I think we have a mix of Italian and Dutch, open attacking but really organised, defensively don’t give spaces and always in the right position.

“I’ve worked with Thiago who played in Chelsea and Lyon, and he said Portugal is the most difficult league to play because some teams don’t know what they can do as a footballer, but play to not let opposition play. That is still true, some coaches study very well the opposition, and organise their teams just to block what the opposition is able to do. Maybe the culture contributes, as coaches know if they lose two games they are sacked, so they protect themselves.”

Gomes, however, feels part of a more proactive generation.

“My idea of football is the pure idea, of when a kid as a ball at his feet on the street or in school, to play. The foundation of the game is the quality on the ball. I still believe if we control the ball, play with the ball, even if it’s against a stronger opponent, they can’t do anything because we have the ball. So in one sentence it’s this: controlling the ball.”

It is one other reason why Portuguese coaches are set to take control of so many European clubs for the foreseeable future. You’ll be able to see why by watching sides like Gomes’ Maritimo.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments