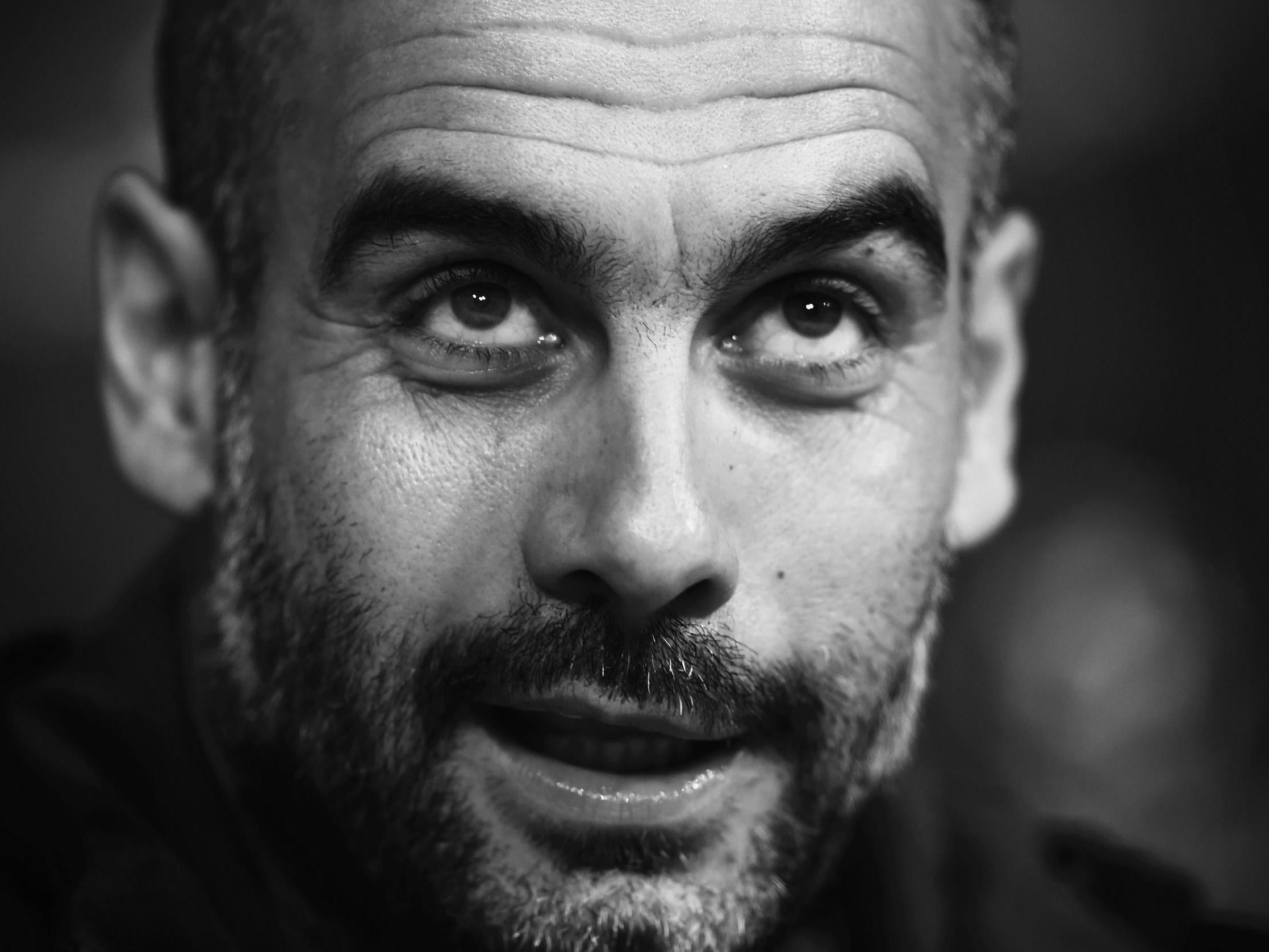

How Pep Guardiola’s 2008 Barcelona appointment changed football forever

It is no exaggeration to describe Guardiola’s appointment at Barcelona as one of the most influential moments in football, which has conditioned the modern game right down to the grassroots, writes Miguel Delaney

Pep Guardiola knew that, before he could even change results, he would have to change minds. Because, as remarkable as it is to think now, his initial appointment as Barcelona manager in summer 2008 wasn’t just doubted as a massive risk due to his extreme inexperience. It was also viewed as a cynical political use of the symbolism a club youth graduate represented, in order to insulate the Joan Laporta presidential regime from increasing criticism at a difficult time for the club. Guardiola knew he had to set the right message immediately.

“I’m ready to overcome this challenge and believe me, if I didn’t feel that, I wouldn’t be here,” the then 37-year-old proclaimed at one of his introductory press conferences, after being promoted from the Barcelona B team. “I know that we have to start work quickly and intensively, whoever wants to be with us from the start will be welcomed. And the others, we will win them over in the future.”

The rest, well, is so much more than history. Guardiola didn’t just win the others over but won everything at Barcelona, and thereby did so much more than change minds. He changed the entire game.

That is why it’s more than history. It is the present and the future.

It is no exaggeration to describe Guardiola’s appointment at Barcelona as one of the most influential moments in football. It has almost entirely conditioned the modern game from the top level to the grassroots and looks set to do so for some time. Former AC Milan manager Arrigo Sacchi has frequently described Guardiola’s Barcelona as marking “a before and after in world football”, and recently reasserted this view at the Festival dello Sport in Trento.

“The last 50 years in the sport have been a constant evolution from Ajax to Holland, Milan to Guardiola’s Barcelona,” the Italian great said. “Without evolution, the sport is dead. Without risks, you remain in the past, whereas innovation makes you change every year.”

The teams referenced are pointed, because they reflect how Guardiola obviously didn’t invent pressing, or possession or any of the other principles of the Johan Cruyff philosophy. His innovation - as the true evolution of ideas tends to go - was to reinterpret and properly reintroduce those principles for the modern game so that his whole approach has had as profound an effect on how the sport is played and coached as pretty much any figure, team or tactic in history.

As regards a description of that approach, Guardiola has always bristled at the simplistic and almost twee-sounding ‘Tiki-Taka’ title. He’s right because it’s really a sophisticated combination of possession and pressing that are synchronised through elaborate positional play. That combination, as well as the extent of Barcelona’s success and example of their play, led to the whole sport being exploded open and multiple other consequences and so much of the modern game links back to it.

That explosion was most clearly expressed in the most fundamental of measures: goals. The average-per-game in the Champions League shot up from 2.47 in 2007 to 3.21 last season - a quantum leap. It was a leap first fired by the basic adventure of Barcelona’s play, with the natural will to mimic it initially just leading to more open matches.

It was the deeper replication of the way they did it, though, that really had the effect. Youth coaching began to prioritise the ball-playing technique that Guardiola’s football championed and so many managers realised the value of pressing, while modern sports science allowed the unprecedented sustenance of it. Pressing has actually now become the game’s dominant quality, getting ever faster and shaping how every team sets up. Uefa's own technical reports even describe this as "the Guardiola effect".

So, his Barcelona have ultimately been responsible for the pace the game is now played at and the space that is used in it, the openness and the number of goals at the very heart of prevalent debates over whether managers like Jose Mourinho are past it.

The majority of recent winners in the major leagues and Champions League - Manchester City, Barcelona, Real Madrid, Bayern Munich, Juventus, Chelsea, Paris-Saint Germain - play with distinctive hallmarks of the Guardiola way. The current dominant football approach comes from what he did at Camp Nou.

In changing minds, he changed the game.

To fully appreciate just how much football has changed, it’s worth considering a match from before Guardiola's appointment that has become relatively infamous because of one line. Mourinho’s Chelsea and Rafa Benitez’s Liverpool met in the 2006-07 Champions League semi-final, with the highly constrained nature of the occasion prompting Argentine legend Jorge Valdano - one of football’s foremost thinkers - to derisively talk of “shit hanging from a stick”. While that quote has become so memorable, the erudite words which followed it are actually more relevant.

“Put a shit hanging from a stick in the middle of this passionate, crazy stadium and there are people who will tell you it’s a work of art,” Valdano wrote in Marca. “It’s not, it’s shit hanging from a stick... Chelsea and Liverpool are the clearest, most exaggerated example of the way football is going: very intense, very physical and very direct. But, a short pass? Noooo. A feint? Nooooo. A change of pace? Noooo. A one-two? A nutmeg? A backheel? Don’t be ridiculous. None of that. The extreme control and seriousness with which both teams played the semi-final neutralised any creative licence, any moments of exquisite skill.

“If Didier Drogba was the best player in the first match, it was purely because he was the one who ran the fastest, jumped the highest and crashed into people the hardest. Such extreme intensity wipes away talent, even leaving a player of Joe Cole’s class disoriented. If football is going the way Chelsea and Liverpool are taking it, we had better be ready to wave goodbye to any expression of the cleverness and talent we have enjoyed for a century.”

This was actually something Guardiola himself had recognised three years beforehand, as he reflected on his increasing irrelevance as a player in a searching 2004 interview with The Times.

“Players like me have become extinct because the game has become more tactical and physical. There is less time to think. At most clubs, players are given specific roles and their creativity can only exist within those parameters.”

This was the issue. The game was being physically suffocated. The leading managers like Mourinho and Benitez propagated what Valdano accurately described as “extreme control”. Tactical approaches were rigid and set with little risk and less expression and it led to containment as much as control. Muscularity reigned, but it was relatively unmoving. The lowest scoring Champions League seasons since its final 1999 expansion were 2003-04 and 2006-07, with both at 2.47 goals per game. These seasons involved, respectively, Mourinho’s career launchpad win with FC Porto and then Benitez’s second Champions League final with Liverpool.

Football was essentially locked up between these tactical approaches and the muscularity that at that point came from initial developments in sports science.

Guardiola didn’t pick this lock. He blew it open. The sudden willingness to open out and attack was, to quote Bruce Springsteen on hearing Bob Dylan’s ‘Like a Rolling Stone’ as a teenager, “like somebody’d kicked open the door to your mind”.

Guardiola turned the game’s thinking upside down by turning the pitch upside down. So many of his players have spoken about having to effectively learn a new way of playing under him. Guardiola first of all simply opened out pitches that had up to then been so constrained. His team would play much higher up the pitch, while pressing opposition so high up the pitch, with what they did with the ball in between bringing floods of goals. There was risk with that high line, sure, but so much rigour behind it. That combination of possession and pressing also brought the idealised synchronicity between individual expression and collective organisation.

“The biggest game-changer in football,” one figure who has worked with Barcelona proclaims to the Independent. “What was so different was the sense of directional possession he instilled in the players. They intentionally pulled teams around and then exploited the gaps.”

And exploded with goals. In Guardiola’s first 10 league games as Barcelona manager, they scored at least six times in four different matches. Such unprecedented scoring heralded the unparalleled dominance to come as Barcelona won Spain’s first ever treble in that first 2008-09 season. Seven of Guardiola’s players would then appear in the Spanish national team’s 2010 World Cup final win, forming the core of the first international side to win three successive trophies, before Barcelona then added another Champions League in 2010-11 to go with another two league titles.

Guardiola football was on top of the world, ruling the game, but was also doing something deeper further down.

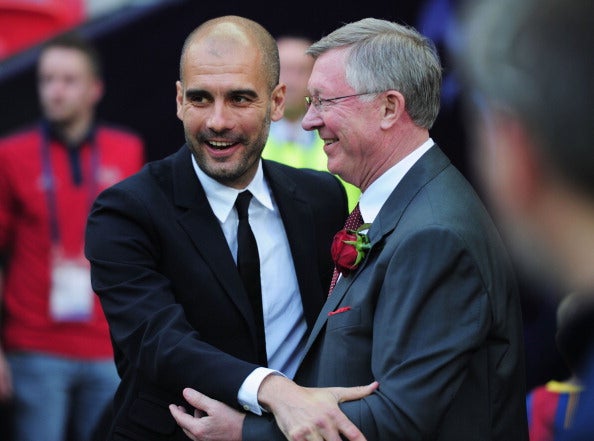

Manchester United great Michael Carrick played against Barcelona in both of those Champions League finals and couldn’t help noticing a connected shift.

“I think I probably did [see a shift], yeah,” he tells the Independent. “There was always that possession-style, like with Holland, but definitely for that three or four-year period, Spain were almost untouchable. Barcelona were pretty much known as the best team at that time and because of the way they did it, it was so nice to watch, so easy on the eye. Everyone’s second team really in Europe was Barcelona because of how they played the game, so entertaining - arguably the right way.”

This was what was so captivating, the allure, why they initially became so influential. Like with so many of the great sides through history - from Real Madrid 1960 to Brazil 1970 - so many players and teams were inspired to just… play. To express themselves. Teams like Blackpool began to pass out from the back, but while that was someway superficial mimicry, that was not where it stopped.

One of the most crucial effects of Guardiola was how it changed coaching. One of his edicts is that the ball must always be played out from the back, absolutely never played long, and this was what youth development came to address. So many coaches from all over Europe now speak of how players were effectively trained to be “universalists”, first of all adept in basic technique before anything else. This was most visible with defenders, where ball-playing became more important than ball-winning.

“That could be seen right down to the foundation phase!” FA elite coach David Powderly explains. “It’s important to have coaches at the right age, and they should be paid the most.”

The ideas spread far, as Bayern Munich official and former international Matthias Sammer explained in a 2014 interview with FourFourTwo.

“When I was working for the German FA, we closely analysed Barcelona from the personality of their coach to their style of play," Sammer said. "The team had an identity. It had individuality, quality, stamina, style, class.”

And now we’re in 2018 and so many of the game’s players have been coached along these lines. They have the technical base to play in the manner Guardiola idealises. But it’s not just how they can play the ball, it’s how they’re made to think and made to press.

The extent of Barca’s pressing had such a profound effect, and made such a tangible difference, it is now the element that shapes the modern game more than anything else. It is something all of the top teams practice, something that defines so many of the most prominent modern coaches from Jurgen Klopp to Antonio Conte.

“The focus is now not on the ball, but around the ball and away from the ball,” Powderly explains. “It’s become a game of chess. Coaches will change players and type of press depending on how the opposition press.”

In fact, it has evolved so much it has gone far behind Guardiola’s initial idea of pressing, forcing even him to adapt.

It is said to have consumed his thoughts more than anything else in the build-up to this season - how his record-breaking Manchester City side squandered the chance at the Champions League because they couldn’t live with the speed of Liverpool in the quarter-finals.

As much as that tie was an outlier in City’s spectacular 2017-18 season, it was entirely in keeping with the prevailing trends of the Champions League, particularly in the lusciously tense latter stages: high technical quality, high speed, and high scoring rates. The electricity that has led to so much drama since Guardiola opened the game up. Last season’s average of 3.21 goals per game is something that hasn’t really been seen since the 1960s, when Catenaccio - and the very idea of defensive football - properly spread.

This is what is key. Guardiola’s influence has been as profound as that of that infamous Italian tactic. He has effectively undone its effect.

After Nereo Rocco’s AC Milan won the European Cup in 1963 with the first prominent use of that defensive approach - and some highly cynical tactics - its success brought a long-term decline in goals scored. The inevitable spread of those ideas ensured European Cup averages began to radically drop in the 1960s and stayed roughly around 2.5… until the last few years.

This is what Uefa mean by the “the Guardiola effect”. This is what has changed.

He didn't just change minds. He changed how everyone in the game thinks.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments