The story of FK Qarabag: How a team born from war now prepares to host Chelsea in the Champions League

This evening, a small club from a ruined ghost town labelled the 'Hiroshima of Caucasus' will host the Premier League champions in their maiden Champions League campaign

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Miles from anywhere, Aghdam’s Imarat Stadium lies in ruins.

If things had been different, the old Soviet-era ground might have been preparing this week to host football under the world’s spotlight, with preparations all but completed for the visit of Chelsea to this corner of rural Azerbaijan in what would have been a whirlwind evening of Champions League excitement.

Instead, the only eyes falling on the Imarat are those of Armenian military snipers, stationed around what is left of Aghdam to keep curious interlopers away from this ruined ghost town.

150km to the east in the Baku suburb of Suraxani, Musviq Kuseynov chokes back a tear as he remembers his final day in Aghdam in 1993, days before the city fell to the Armenian occupation.

A centre-forward for FK Qarabag, Kuseynov had relocated along with his teammates to the town of Mingecevir several months earlier at the turn of the year, as the aerial bombardment of Aghdam made the city uninhabitable to all but those who had stayed behind to defend it. Having returned briefly to visit his brother, he remembers a bonfire one evening in a friend’s back yard.

“A missile went over head,” he recalls. “We could recognize by that point in the war exactly where the bomb was going to fall, whose house it was going to hit. We could tell from the sound. After that I never went back to Aghdam.”

On Wednesday, as Qarabag prepare to host Chelsea at the Baku Olympic Stadium in the nation's capital, Kuseynov balances his reputation as a goal-scoring legend of the five-time Azerbaijan champions with work as manager Gurban Gurbanov’s number two.

Back in his playing days, having made his debut as a 14 year-old under the tutelage of Qarabag’s iconic former manager and Azerbaijan war hero Allahverdi Bagirov, Kuseynov plundered over a hundred goals in a career that spanned before, during and after the club’s evacuation from Aghdam. It was a trauma which nearly pushed Qarabag into extinction.

“It was something extraordinary,” says Kuseynov.

“They loved great football in Aghdam, and during the war that’s what we gave them. But the calm in Aghdam was gone. We continued to play football, but it had become an obligation. Every minute you knew that a bomb could fall and change your life.”

The Armenia-Azerbaijan war claimed between 25,000-35,000 lives from 1988-1994. The land over which that conflict was fought was Nagorno-Karabakh, a mountainous region that sits just inside the Azeri border but which has historically been populated by an overwhelmingly Armenian majority.

At the border where Nagorno-Karabakh meets Azerbaijan proper, Aghdam sits in prime sight of the Karabakh capital city and Armenian stronghold Stepanakert.

When, in 1988 the Armenians in Stepanakert made an unsuccessful play for independence, this hitherto insignificant sleepy township suddenly became a key strategic outpost in a brutal international war, one in which victory and defeat could only ever be total. 24 years later the conflict remains on ice, with leaders on neither side prepared to soften their rhetoric over the territory.

When in 1988 the shells began to fall on Aghdam, all normalcy ceased. As fire fell from the sky, daily life became twinned with a struggle to locate a spirit of renewal from amongst the fear.

“Before the war we had been the only club I think in Azerbaijan that existed using only local players” says Qarabag’s former captain, Shahid Kasanov.

“The team was native for the people. Everybody was from Aghdam – the players and the fans. They were their relatives and their neighbors. It was special, it was native. The team was their own. The club and the stadium became a temple.”

“How would I compare with life before the conflict?” says Kuseynov.

“I couldn’t. There is no comparison. When peace turns to war, it is every difference you can imagine. It is impossible for you to imagine the kind of traumas Aghdam experienced in such a short time. Every day we would wake up to news of more martyrs.”

Qarabag’s Imarat Stadium was hit by Armenian projectiles in those first two years of the war, twice, although on both occasions the place was empty. This, says Kuseynov, was only by the grace of god. Such was the damage inflicted by the bombs that it is likely nobody would have survived.

The club’s training base was hit too, one night in 1992. Had the missile come a few hours earlier, the casualties would likely have numbered more than a dozen. Instead, the players cleared away the debris from the ruined buildings that had fallen on their pitch and held training as normal.

The turn of 1991/92 brought with it an escalation in the Armenian aerial campaign against Aghdam, but still the Imarat Stadium remained full on match-days.

During the 1992 season, the first of the newly independent Azerbaijan Premyar Liqa after the dissolution of the USSR, the Armenians began to shell the area around the stadium during Qarabag’s home game against FK Insaatci from the city of Sabirabad, more than 150km east of Aghdam.

When the shelling started, the Insaatci players to a man fell instantly to the ground, unsettled by the soundscape of the war. Kuseynov, Kasanov and their teammates, hardened against the carnage all around them, simply carried on.

“It’s a strange thing,” says Kuseynov reflectively, “how quickly you become used to war.”

Aghdam fell to the occupation on 23rd July 1993. Ten days later, Qarabag beat FK Khazar from the city of Sumgayit 1-0 to claim their first ever championship title, but rather than ushering in an period of sustained success the exiled club went into a steady decline. By 2001, rudderless and without a home, Qarabag were virtually bankrupt.

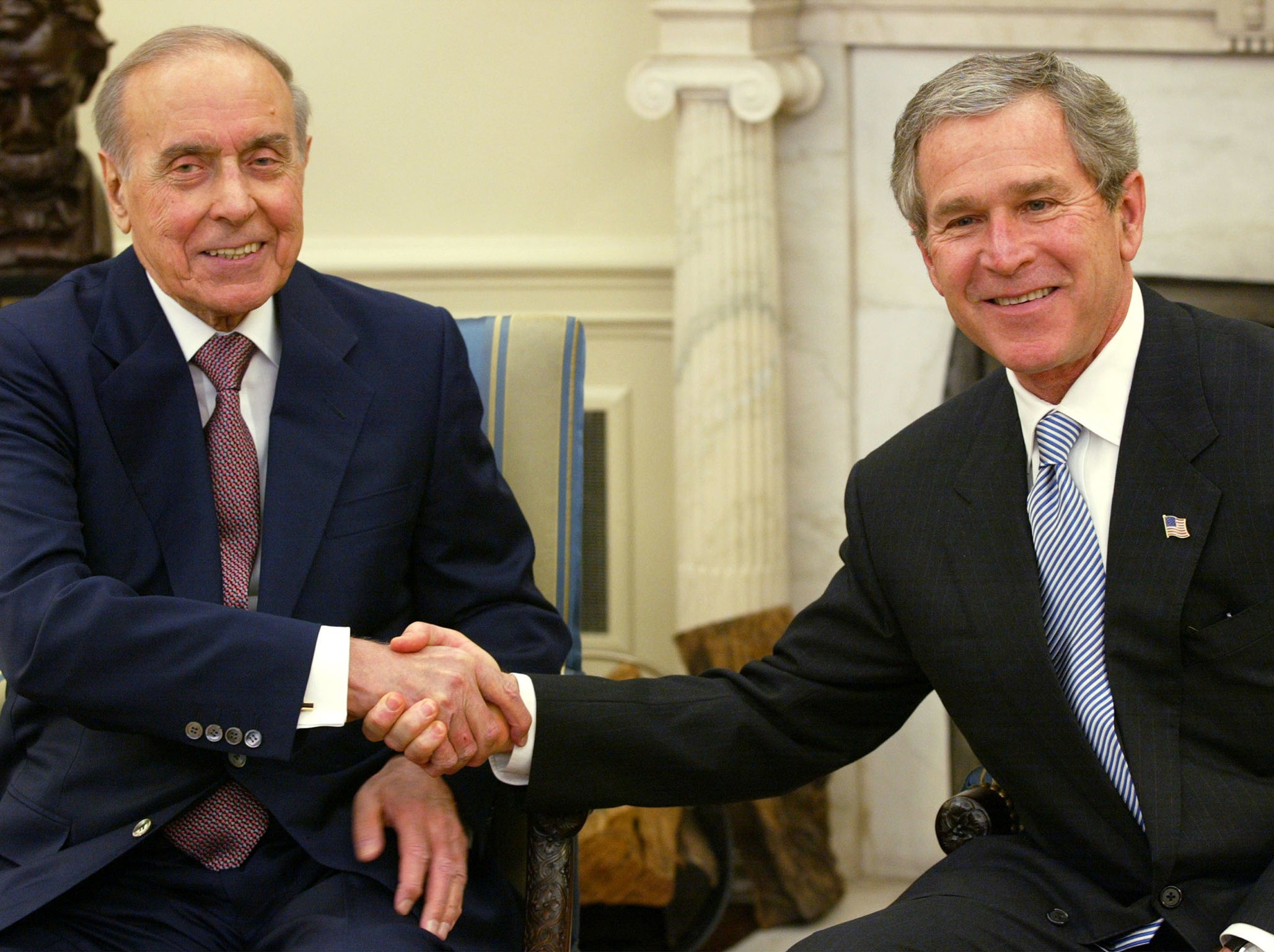

According to the club’s head of communications Nurlan Ibrahimov, the green light for the state-backed holding company Intersun to assume control and financial responsibility for Qarabag came from Azerbaijan’s former president, the late Heydar Aliyev. The subsequent revival of the club’s fortunes has been heavily politicized.

The relationship between power and society in Azerbaijan is an uneasy one. Intersun are controlled by two Iranian-born brothers, Abdolbari and Hasan Gozal, whose connections to the presidency of current leader Ilham Aliyev have been investigated by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists in Baku, revealing an interlocking network of vested interests which tie the Gozals, and by extension Qarabag, into the highly secretive world of Azerbaijani business.

Multi-billion dollar contracts have been handed to companies controlled by the two brothers, including from the country’s state-owned oil company where Ilham Aliyev was an executive before becoming president.

The brothers’ various companies, all existing under the Intersun umbrella, have benefited from $4.5billion in construction contracts around Baku, all financed by the state’s vast oil-wealth. Hasan Gozal is also listed as a director of three off-shore companies set up in the names of Ilham Aliyev’s daughters, Arzu and Leyla.

Intersun’s bankrolling of Qarabag has given the state of Azerbaijan its most conspicuous opportunity to align itself internationally with the disputed lands of Nagorno-Karabakh. It has also given the country’s people a reason to feel hopeful about the future as they cope with the continued fall-out from the conflict.

When Qarabag beat Copenhagen in their Champions League play-off first leg, more than 31,000 spectators were packed into Baku’s Tofiq Bahramov Stadium – named after Azerbaijan’s most famous sporting export, the linesman whose flag awarded England a third goal in their 1966 World Cup final win at Wembley – where the club have until now played their European fixtures.

Typically for a Premyar Liqa match, the club’s 5,200-capacity Azersun Arena home is less than half full. For the Group Stages they will have even greater backing, with the club moving temporarily into Baku’s stunning new Olympic Stadium just outside the city centre.

The Champions League is the holy grail for Qarabag. Its currency cannot be clocked by any conventional metric, and its transformative potential is immeasurable. Across the border in Armenia, however, any mention of the Karabakh name (the discrepancy in the spelling is a product of the transliteration from Russian to Turkish) as synonymous with Azerbaijan is anathema.

Nagorno-Karabakh – or Artsakh to its natives – is historically Armenian in its heritage, owing its legal status within Azerbaijan to legislation introduced by Joseph Stalin in the embryonic days of the USSR.

Its mountainous terrain makes Stepanakert and the seven surrounding provinces that comprise the breakaway de facto republic intensely isolated, the capital sitting some 2,600 feet above sea level and only accessible via a grueling six-hour bus ride from Yerevan through the winding hills.

“They tell the history they want to tell” says a spokesman for the First Armenian Front, who goes only by the name Seroj. The Front were set up in 2006 to fight for improvements to the state of the game in Armenia, though much of their work is focused on improving conditions for soldiers on the Karabakh front line, which remains active.

“It’s a small part of their wider propaganda game. They name the club Karabakh and then promote it as being Azerbaijan. It’s psychological.

“To us in Armenia, as football fans, it is hurtful. We don’t have a team that bears the name Artsakh in Armenia because of FIFA and UEFA rules. Maybe that’s because we don’t have the same money in Armenia as they do in Baku and Azerbaijan.”

With qualification for the Champions League, the Azerbaijani state’s interest in Qarabag has only intensified. What effect that will have on the frozen nature of the conflict is difficult to predict. The frontline has scarcely moved in 24 years of war, and neither Baku nor Yerevan has showed itself to be in any mood for softening its position on Nagorno-Karabakh.

Now, though, it’s time for the football to take centre stage.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments