Bayern Munich and Real Madrid form one of the Champions League's richest and most intense historical rivalries

Much is at stake when two of Europe's greatest clubs go head to head in the Champions League quarter-finals, but this great rivalry is not as bitter or as passionate as it once was

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.You couldn’t say for definite that Bayern Munich had bided their time and waited a year to respond to comments by Real Madrid players, but you could certainly say there was an edge between the two clubs by the time they met again, in 2001-02.

A proper rivalry had developed, much spikier than today’s. Because, although the German champions had defeated Real in the 2000-01 Champions League semi-finals with an impressively defiant display, Spanish midfielder Guti wasn’t that impressed.

“They looked like a team that was playing to avoid relegation,” he sniffed.

The deposed 1999-2000 champions Real felt that they were still a far superior side to Bayern, and there was even some talk around the Madrid camp about how such a performance from a similar club had gone against the spirit of the competition.

So, when the Germans again beat Real in the first leg of the following year’s quarter-final, manager Ottmar Hitzfeld had a few words of his own.

“I don’t understand all this discussion about Madrid being the best in the world - we always beat them.”

That wasn’t quite true, as the very next match would prove. What was true, and what this very trend of matches would emphatically prove, was that there was a period when Real and Bayern always seemed to be meeting - even more than Bayern and Arsenal or PSG and Barcelona.

These two club were drawn against each other four times and met in eight individual games across three seasons from 1999-2000 to 2001-02, making it the fixture that has been played most over the shortest period of time in over 60 years of European Cup and Champions League.

It is arguably fitting that is the case, and that it happened at that exact time with one of them eventually lifting the trophy in each of those three years, because the two clubs came to define and dominate the newly expanded competition along with Barcelona.

This was a signpost of the superclubs that we see now. The previews to Wednesday’s night rematch will mostly see recalls to a Bernabeu fan trying to attack Gerd Muller in 1976, or the 4-0 humiliation of Pep Guardiola’s side at the Allianz Arena in 2014, but it was their series of meetings around the turn of the millennium that were the most meaningful; the most intense; the most symbolic.

Just as the Champions League had been forced to grow to 32 clubs in 1999-2000 for economic reasons, two of their truly economic powerhouses grew to a new level with it, although through very different approaches.

That is why Guti’s words about Bayern’s approach and the spirit of the competition also had their deeper significance, given the mindsets that seemed to inform how they went about business.

While Real would during this period embark on their ostentatious Galactico policy, when new president Florentino Perez would make a virtue out of spending as much money as possible, Bayern were the complete opposite. They favoured prudence over bombastic proclamations.

“As far as I’m concerned, success that was bought with a credit card is nothing that would make me proud,” then-business manager Uli Hoeness said of their policy.

“When I win the Champions League, I want to make a profit.” He helped make a superb collective, rather than the collection of superb individuals that Real were.

That difference could be seen in the profiles of the squad, and players prized by one club but discarded by the other.

On taking over as Real president in the summer of 2000, Perez had been persuaded against his own judgement to sign both Claude Makelele and Flavio Conceicao, who technical director Pirri said would give them “the best midfield in the world”.

Makelele would do that and also prove Perez wrong in the long term, but £26m Flavio could barely get a game. When the president asked for an explanation, Pirri merely said “in the game of football signings, there is a mathematical rule: three out of five fail.”

Perez was “appalled” by this, as revealed by John Carlin in his book White Angels, and it went a long way to inspiring the Galactico policy. The president wanted to make sure he only bought those two out of five players who would guarantee success.

Luis Figo, infamously signed from Barcelona that summer for a world-record buy-out, would do exactly that.

Bayern’s squad at the time was not graced by such glamour. Instead, they had signings closer in profile to Flavio, ‘the very good but not necessarily great’ Brazilians that Roy Keane described such great respect for in his first autobiography.

Giovane Elber and Paulo Sergio led the Bayern attack along with Mehmet Scholl and Stefan Effenberg.

Fired by those players as well as a desire to rectify the wrongs of the traumatic final defeat to Manchester United in 1998-99, the Germans put eight goals past Real Madrid across two games in the second group stage of the 1999-2000 campaign, winning 4-2 and 4-1.

The results were no freak. Real were also enduring a torrid season in the Spanish league, and off the pitch. With a spate of injuries, they had lost 5-1 at home to Real Zaragoza, leading to the Bernabeu fans singing “we will burn your Ferraris”.

The situation eventually saw manager John Toshack get into a public dispute over his stand-in goalkeepers and their errors and, when asked by the club to retract his words, told the press that pigs would fly over the Bernabeu for that to happen - a phrase that comically has no meaning in Spanish.

Toshack went, Vicente Del Bosque came in, and all changed. It summed up just how much had changed that a big problem was fixed with one of the most high-profile expensive signings.

It was also a measure of Del Bosque’s man-management. Nicolas Anelka had already arrived with baggage after a controversial £22m move from Arsenal in the summer of 1999, and it only got worse as he effectively isolated himself from his teammates, and then would publicly complain that they didn’t pass to him.

He eventually missed training in protest at Del Bosque’s tactics, bringing a 45-day suspension. It said much about the situation and the dressing room that, when Anelka returned, he found his teammates had emptied his locker out.

By the time the suspension finished, though, Real had many of those players unfit… as well as a semi-final draw against Bayern. They needed Anelka, so Del Bosque worked hard to nuance the situation, using the popular Steve McManaman as a go-between.

It paid off. Anelka scored after four minutes of the first leg to show this eventual 2-0 win this would be a very different game to the group stage, and then hit a key away goal in the second leg shortly after Carsten Jancker had pulled one back.

Real went through to the final and beat Valencia 3-0 as a thoroughly transformed team, before Perez’s election to president so completely transformed the club.

They did genuinely move onto another level for a time, as the Galactico era started. Bayern still had unfinished business, though, and the defeat to Real made them even more determined.

Former Bernabeu defender Ivan Campo admits there was definitely an edge to the rivalry by that point.

“Yes, there was a bit, especially when you have met so often,” he tells the Independent. It’s about the level of football, too. The psychology of it, trying to transfer pressure. We’re also talking about players who are winners, who fight to the limit.”

Bayern were ready for that. By the time they met again in the semi-final the following season, they were ultra-focused; determined not to make any mistakes.

A young Iker Casillas made a rare one himself, feebly letting in an Elber strike for the only goal of the first leg at the Bernabeu. That ensured it was effectively it.

Bayern had an advantage they were never going to let go. The final score on aggregate was only 3-1, but the difference in performance felt so much bigger. Guti may have been bitter about it, but McManaman was only deflated. He described it as a “very, very upsetting” defeat in El Macca, his book on his time in Spain.

“Playing Bayern Munich, when they’re defending a lead in a Champions League semi-final, is like being suffocated by a kingsize, winter-weight duvet,” McManaman said.

“You’re stifled. They’re disciplined, keep their shape and work hard in being unerringly defensive. It’s horrible… you could sense the desperation rising. We had as many forwards on the pitch as possible, but nothing worked. We were smothered 2-1.”

Now they were to be motivated in the same way Bayern were.

“That defeat haunted us all. It made us think, and tinker around a bit, so in a way it helped to prepare for the following year.

“We knew we should’ve beaten Bayern Munich, and then when you saw the final, which wasn’t a classic, with Bayern beating Valencia on penalties, we still felt convinced the best team in the competition was us and we’d missed a huge opportunity.”

Campo is in full agreement. “Macca is absolutely right,” he says. And Real eventually got it right when the two sides met again in the 2001-02 quarter-finals, although Bayern again made them work to the limit.

Bayern had actually scored two late goals to win their home first leg 2-1, prompting Hitzfeld’s remarks about how they always won. Not this time. Zinedine Zidane had by then joined Figo as the next Galactico, but it was one of Real’s less stellar names that made the difference.

Ivan Helguera eventually scored the 69th-minute header that gave them the advantage, before Guti secured a place in the final.

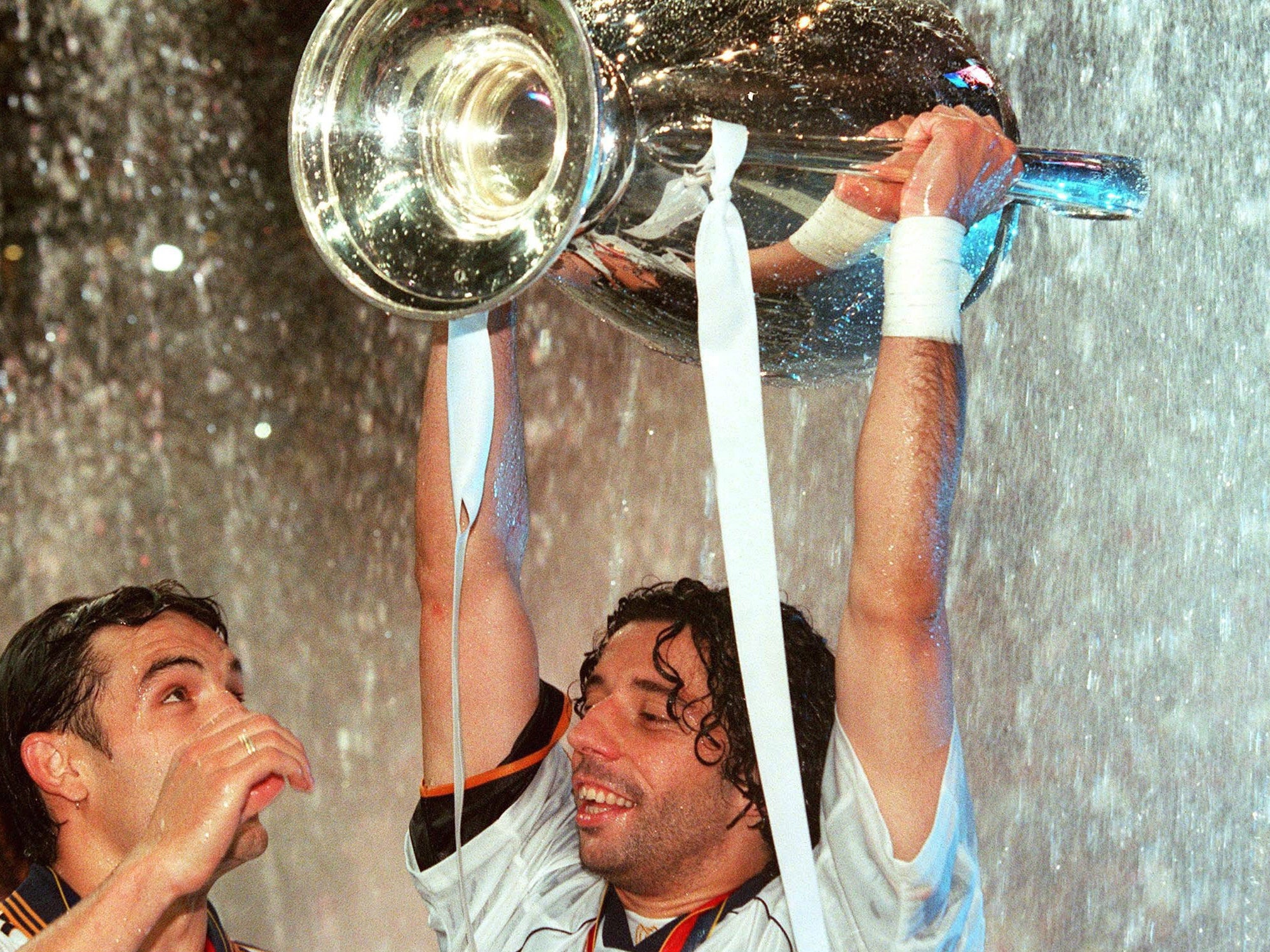

Real would again go on to lift the trophy, meaning the winner of this pairing had produced the winner of the competition for all three seasons since the 1999-2000 expansion. It had become the Champions League’s defining match.

The event has evolved even more since then, while inspiring a lot of debate in how that evolution has seen the influence of the economic strengths that first powered that era only grow. It has meant both Real and particularly Bayern have evolved since then too, but there still hasn’t been a rivalry as intense or as evenly matched as that.

Not even Wednesday, after all, will have the same edge.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments