The birth, death and future of the European Super League

The league’s founder members broke cover on the night of Sunday, April 18.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Late on the night of Sunday, April 18, 12 of Europe’s top clubs – including the Premier League’s ‘Big Six’ – announced themselves as founder members of a new European Super League, governed by the clubs.

Within 72 hours it had collapsed, with all six English clubs having withdrawn amid Government pressure and fan outrage.

But what motivated those behind it, how and when did the idea gain traction, why did it fail so spectacularly, and is UEFA’s revamped Champions League a Super League by another name, as a Premier League fans’ group sees it?

The PA news agency spoke to individuals who were involved in the seismic events of 12 months ago, on condition of anonymity.

Origins

UEFA and the European Club Association (ECA) developed a plan over the course of 2018 and 2019 which effectively granted the 24 best-finishing teams in the Champions League passage to the next season’s 32-team group phase.

Europe’s leagues and fans’ group publicly called it out as a ‘closed league’ and the plans were shelved.

Planning for the Super League that broke cover in April 2021 had been three years in the making. Discussions intensified in early 2020. What differentiated these talks from those that had gone before was that they were being conducted at owner level.

Owners became frustrated, seeing themselves as the ones taking all the risk with their investments, and saw a Super League, free from the threat of relegation, as a path to greater certainty. Real Madrid, Liverpool and Manchester United are known to have been involved from an early stage.

What seems incredible to learn now though is that the initial offering mentioned supporters – how ticket pricing should be set, arrangements for away travel for a continental league, and so on. But by launch on April 18, this ‘finer detail’ had been stripped away and the original press release made no mention of fans at all.

First reports

On October 20, 2020 Sky News reported that Wall Street bank JP Morgan was in talks to provide a financial package to back a new European Premier League. Already by this stage, club owners such as Joel Glazer and John W Henry were taking soundings on how the idea of a Super League would land.

In January 2021 FIFA and the six global confederations jointly released a statement saying they would not recognise any European Super League.

The starting pistol

By the end of March, representatives of Key Capital Partners in Madrid were feeling confident with the number of clubs that had signed binding agreements to form a league.

At the end of that month, a key meeting of UEFA’s club competitions committee on the future format of the Champions League was delayed until April 16. No agreement had been reached between UEFA and the European Club Association (ECA) on the level of commercial control over the competitions the ECA would exert alongside UEFA.

Europe’s big leagues had treated the Sky News report in October as part of the negotiation process, and dismissed it as ‘sabre-rattling’ by the clubs.

But a call that came through to one of the domestic leagues in the first full week of April, identifying the PR firm that would be involved – iNHouse, led by former Downing Street director of communications Katie Perrior – and the proposed launch date, Thursday April 15, put them on high alert.

April 15

The launch date flagged to the leagues came and went. But the threat was still being taken seriously. Sources have told PA that by this point, four Premier League teams were on board with the Super League. By Friday, it was six.

April 16

With less than 48 hours’ notice, communications directors at England’s Big Six clubs were brought together virtually and told about the plans for the first time. All could immediately see how it would go down, but the orders were coming from the very top of their respective clubs, so they had to make it work.

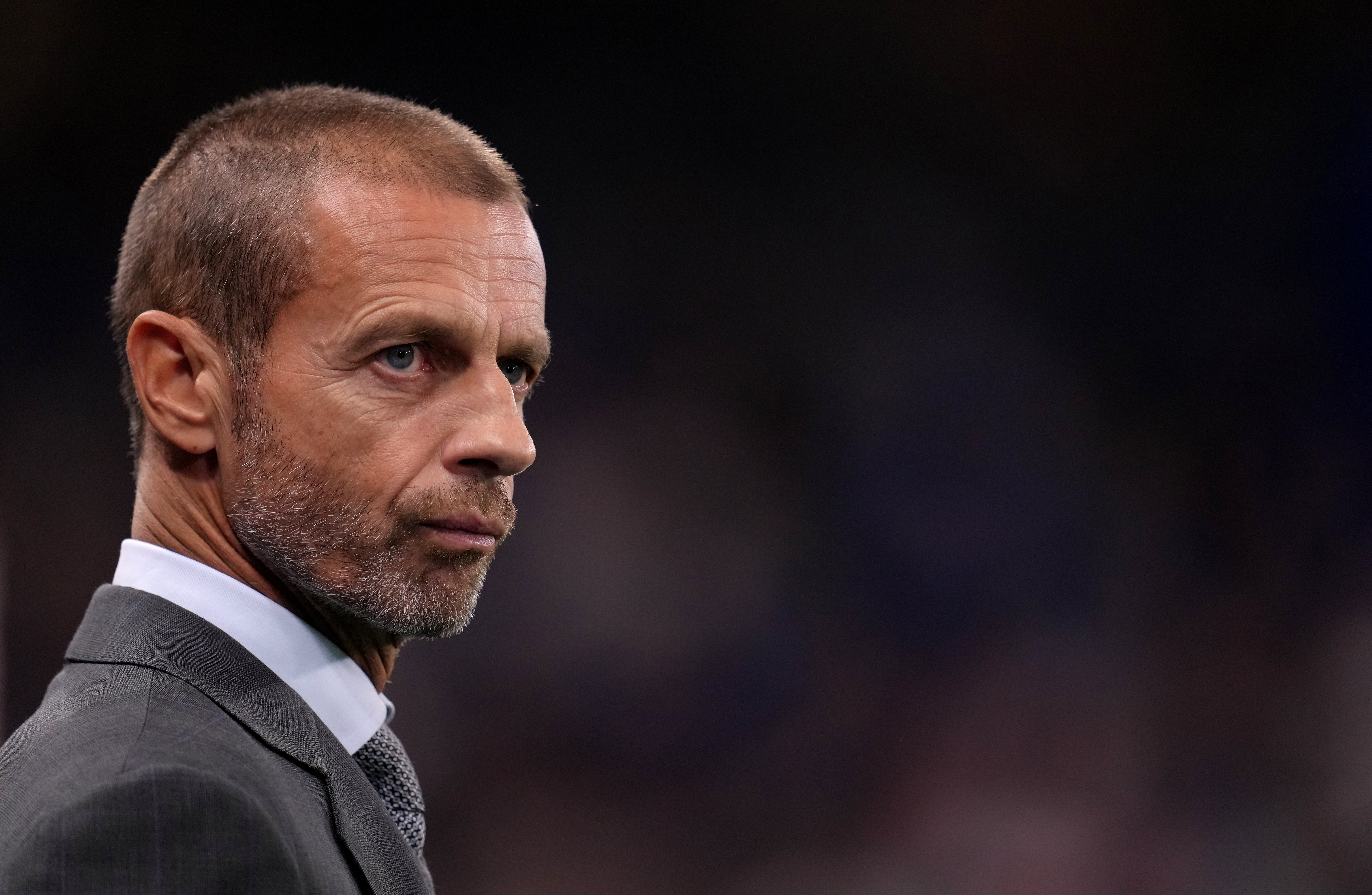

Juventus president and ECA chairman Andrea Agnelli had come on board to the Super League relatively late, but was understood to be key to driving the Sunday announcement. He was not prepared to stab UEFA president Aleksander Ceferin, his daughter’s godfather, in the back at a later stage. To him, it was now or never.

Europe’s leagues sounded the warnings they had been given to UEFA on Friday, but were told not to worry. After all, UEFA’s club competitions committee, which included strong ECA representation, had just given the new Champions League format its approval that afternoon.

April 17

Fans’ representatives began to hear about the Super League plans from the football authorities.

European league sources were told on Saturday that Ceferin and Agnelli would release a joint UEFA/ECA statement killing the rumours. It never came, and as Ceferin later recalled, Agnelli turned off his phone.

April 18

The Super League 12 wanted to wait until court documents had been lodged in Madrid, designed to protect them from legal action to shut the competition down, before announcing.

By now UEFA and the leagues were preparing joint statements but were concerned about confirming something that at this point was still not real.

Premier League chief executive Richard Masters wrote to all 20 English top-flight clubs on the Sunday urging those he knew to be involved to walk away, that the project would collapse without them.

From the Super League side, another cause for delay was the fact that so many of their clubs were in action that Sunday – they did not want players and managers, who knew nothing about the plans, having to face questions.

By the time the clubs published their joint statements, at around 11.30pm, statements condemning it had come from the Premier League, on its own and jointly with UEFA, and the Football Association, and had been thoroughly denounced on Sky Sports by Gary Neville.

Nobody defended the ESL amid the storm of protest that had whipped up from one o’clock in the afternoon. The league was effectively dead on arrival.

The aftermath

Condemnation came from a wide variety of quarters, including the British political establishment and even the Duke of Cambridge.

Protests took place at Elland Road, where Leeds were hosting Liverpool. One of the Reds’ own players, James Milner, spoke post-match to say he did not like the Super League and hoped it would not happen.

Still, no-one in England came out to be the figurehead.

By Tuesday, Prime Minister Boris Johnson convened fans’ groups and the football authorities to determine what could be done. He asked Premier League chief executive Richard Masters whether the clubs could be excluded from the league. Masters is understood to have replied that legally the league had a good case, but not a perfect case. It was at this point that Johnson vowed to drop “a legislative bomb” on the clubs.

Across London, Chelsea fans gathered to protest against their club’s involvement in the ESL. The Blues were the first to indicate to PA, unofficially, their plans to withdraw, before Manchester City confirmed their exit.

By 11pm – less than 48 hours since stating they were in – all six English clubs were out.

The future

Will a Super League come again? Many informed observers who spoke to PA saw no chance of it being resurrected for a generation at least.

But supporters, and sources within Europe’s domestic leagues, fear it is right round the corner, in the shape of UEFA’s plans to revamp the Champions League.

These promise significantly more matches – 10 instead of six – and to provide protection to fallen European giants by way of the proposed co-efficient qualification places.

Some privately even feel that fans were used by UEFA to block a competitive threat – that it was not opposed to a closed league at all, it just did not like the idea of someone else running it.

Will UEFA listen to fans at this critical juncture? A decision is due from UEFA’s executive committee on the new club competition format on May 10, with talks on how the revenue from these is split to come later in the year.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments