The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

The Big Climb: Pablo Escobar’s brother, the story of Efrain Forero and the notorious Vuelta a Colombia

Book extracts: In a new book exploring the history of cycling in Colombia, Stephen Norman recounts some of the people who brought the country’s love affair with the sport to life

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The best known – if not the most successful – drug fuelled cycling enterprise was Bicicletas Ositto. Bicicletas Ositto was a bike maker of sorts owned by Pablo Escobar’s older brother Roberto ‘Osito’ (‘little bear’).

A cyclist himself in the 1960s, he had once arrived at the finish of a race in Medellin plastered in mud. “I don’t know who this is,” said the race commentator, “his race number and his face are so covered in mud, he looks more like a bear.” So he was known as Osito, the little bear, ever after (he called his company Ositto with a double T because he thought it had an Italian flavour and Italian bikes were cool).

Roberto was a serious cyclist in his own right. As a child, he had an old touring bike which he painted with his fingers because he loved it and had no paintbrush. He used to carry his little brother Pablo on the handlebars. One afternoon in 1958, he and Pablo climbed the Alto de Minas and watched Fausto Coppi and Hugo Koblet go by, on their way to humiliation by Hoyos and Medina in the heat of La Pintada and the slopes of the Alto de Minas. That was the afternoon his heart was set on becoming a real cyclist.

And he succeeded. He had ridden in the Vuelta and the RCN and had several stage wins to his name. He trained in the Antioquian team alongside Cochise. In 1965, aged 18, he and Cochise took part in the 100 kilometres team time trial in the National Cycling championships, and came third. That same year, he rode in the Vuelta a Colombia and finished 38th. In 1966, he rode again and finished a creditable 32nd.

Pablo and Roberto continued their interest in cycling after Roberto retired from racing. Pablo bought the building which became Bicicletas Ositto’s cycle factory.

Visitors to the facility were surprised to find a modest workshop rather than a production line. But still, in 1980, Ositto entered its first team for the Vuelta a Colombia. The bikes were proudly labelled “Ositto” but the frames were actually made by José Duarte, Colombia’s premier frame maker. According to Duarte, Pablo himself used to visit the frame maker’s shop in Bogota in person, to check up on progress.

Pablo Escobar was not the right shape for cycling himself. His love was fast cars, and during the late 1970s and 1980s he raced competitively.

But he was a genuine aficionado of cycling. He and Roberto used to ride around on a Vespa scooter, supporting their team, or by helicopter if the stage was too far away.

Pablo had a private velodrome built just above El Poblado, a suburb of Medellin. Roberto would assemble teams of top quality Colombian cyclists to race round it. And bet huge sums on the outcome, of course.

By all accounts, the drug lords in the 1970s and early 1980s were socially respectable. They did not advertise or even consider themselves to be criminals. They were just rich, smart Colombians whose generosity made them welcome wherever they chose to spend their money.

As we know now, it didn’t last. Indeed it ended with appalling violence and the murder of thousands of innocent (and many less innocent) people.

Roberto was captured by the police in 1992 and charged with multiple offences including possession of weapons, drug trafficking, kidnapping, extortion, accessory to murder and escaping from a maximum security prison (not exactly maximum security – he and Pablo had famously walked out of the Envigado prison which Pablo had created for his negotiated incarceration).

In 1993, (by now back in prison) Roberto was partially blinded by a letter bomb, just 17 days after Pablo Escobar was killed by the security forces.

Today he lives with his bodyguards and supplements his income by entertaining tourists.

***

Our story begins on August 3rd, 1948. A young man from the salt mining town of Zipaquira, high up on the Cordillera Oriental, shows up at the start of a local bike race. He is wearing football boots and riding a touring bike and some of the other riders make fun of him. Which makes him angry. He vows to beat them all, which he does. The prize is a wristwatch, which he will proudly display for the rest of his life.

Neither he nor his chastened tormentors yet know it, but on this day a legend was born.

The young man’s name was Efrain Forero. By 1950, he had earned a place in Colombia’s national cycling team. He and his teammates won a gold medal at the Pan-American games in 1950.

Naturally his nickname – and most Colombian riders have nicknames – was El Zipa. “Why,” El Zipa asked himself, “can Colombia not have its own Tour, like the Tour de France or the Tour (Vuelta) of Spain?”

He discussed this idea with his friend Pablo Camacho Montoya, a sports journalist on El Tiempo, one of Colombia’s leading newspapers. By a happy coincidence, the editor of El Tiempo was not only a keen cyclist but also President of the Colombian Cycling Association. The proposition appealed to him, and also to the secretary of the Association, an Englishman called Donald Raskin.

These three agreed to back the idea – if Forero could prove that the course was feasible. Their concerns were not academic. The three Andean corderillas were daunting barriers, especially since the roads over them were unpaved and deeply rutted by rain and trucks. The low country between the mountains was tropical, hot and humid. And back then, the country was governed by a right wing dictator, Laureano Gómez, who was busy pursuing an anti-Communist purge in which many were executed without trial.

But Efrain Forero was determined. To show what could be done, he planned to ride solo over the most difficult stage of the proposed cycle route, crossing the Central cordillera from Honda to Manizales.

Honda is a small, swelteringly hot town on the banks of the Magdalena River, at an altitude of 229 metres. The highest point on the road is the Alto de Letras, at an altitude of 3,679 metres above mean sea level. The climb therefore exceeds 3,400 metres or 11,000 feet, and is followed by a swift descent to Manizales at 2,107 metres.

So one fine day in October, 1950, Forero set out from Honda. Donald Raskin, the secretary of the Cycling Association, and another enthusiast, Remolacho Martinez, followed in a pickup truck. The road was so bad and so steep that the truck could not keep up. The photo below, helps us to imagine the scene.

Halfway up the driver wanted to give up, but Efrain Forero went on climbing, alone. Shaking with cold and covered in mud, he crossed the Alto de Letras and descended into legend. He arrived in Manizales, two hours ahead of Raskin and the truck! The astonished citizens of Manizales carried him, shoulder high, around the town.

The El Tiempo newspaper and the Cycling Association kept their end of the bargain and in an astonishingly short time, the race was organised.

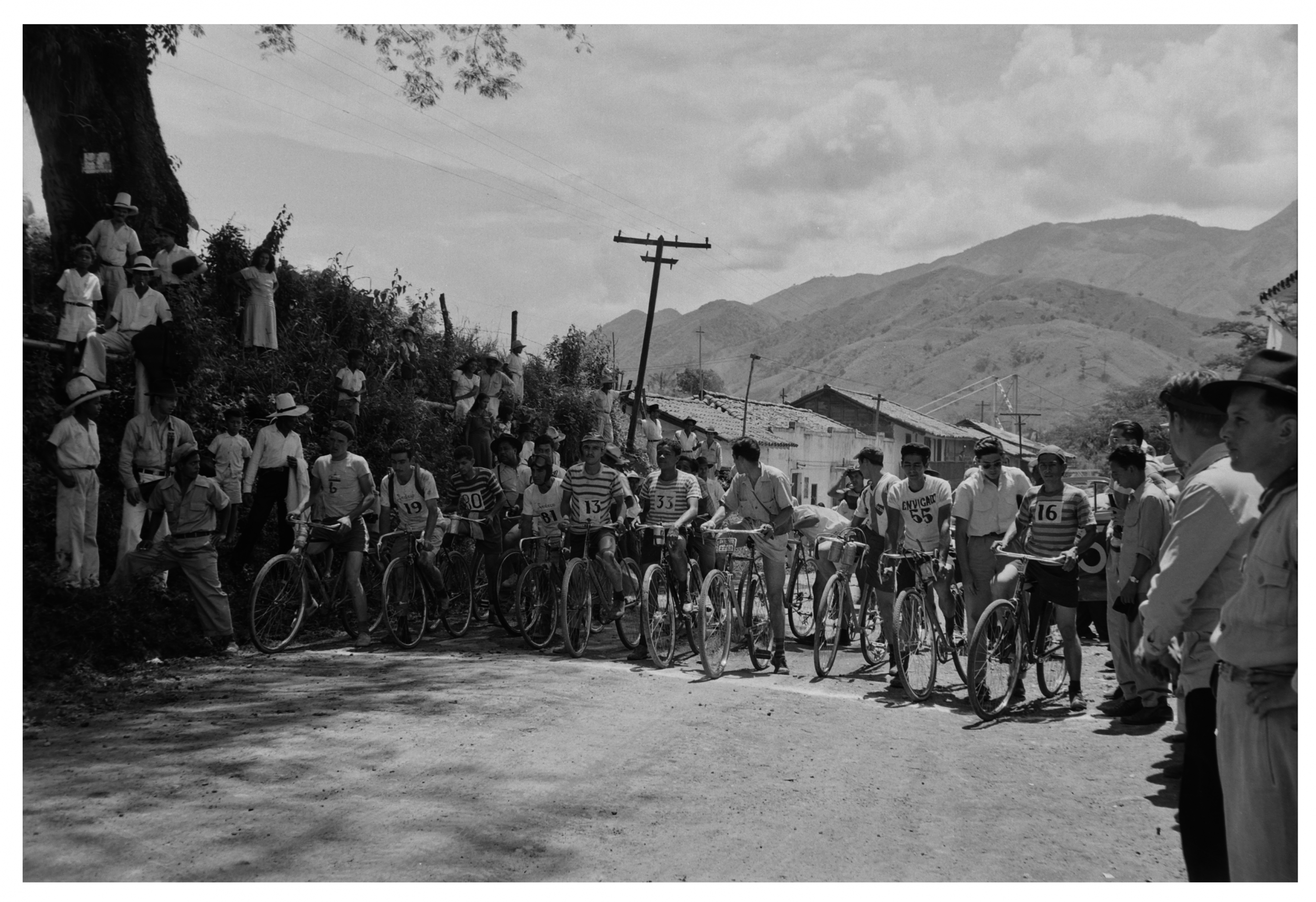

El Tiempo On 5th January, 1951, 35 hardy souls – including of course Efrain Forero – were waved off from Bogota by the editor of El Tiempo.

The first Vuelta was 1,157 kilometres long, divided into 10 stages with two rest days. The riders sweated in the tropical 35 degree heat of the lowlands and froze in the mountains. The descents on dirt roads were dangerous. The wheels and frames of their bikes – mostly locally fabricated – were not up to the stresses imposed on them by the rocks and the ruts in the roads.

The third stage was the ascent of Alto de Letras, the same climb that Forero had undertaken to prove the feasibility of the project. Heavy rain battered the climbers all the way to the top at 3,679 metres, and then harsh sunshine on the way down. A leading Antioquian cyclist, Nel Gil, and Efrain Forero went over the top together. Then Forero crashed and cut his knee. His mother – who was his support assistant – urged him back on his bike. He continued the descent, passing Nel Gil whose front wheel had collapsed!

The radio commentator Carlos Arturo Rueda was moved by his extraordinary resilience to christen him “indomitable”. The name stuck and so the “Indomitable Zipa” was born.

The coverage in Colombia’s newspapers reached stratospheric levels of excitement as the race progressed. According to El Tiempo, a crowd of 7,000 cheered Forero at the finish of the third stage in Manizales. His speed on the final descent was estimated at “close to 100 kilometres per hour” and the running figure seen racing alongside Forero to the finish is confidently identified as “the well-known black runner, Jesse Owens.” What the USA hero of the 1936 Olympics was doing in Colombia was not explained.

The blast of publicity was not confined to the newspapers. Colombia’s radio stations covered the race, with broadcasts which started early in the morning and lasted most of the day. The commentators maintained fever pitch throughout, very different from the laconic style of Brian Smith and Sean Kelly on Eurosport today.

Efrain Forero’s mother was in a support car behind her son but his father was back home in Zipaquira, along with 100 of his neighbours, who clustered round the radio in his pharmacy from 7.30am until 4pm, listening to the commentators.

El Zipa did not disappoint his parents or the nation. Despite mechanical problems and the occasional crash, he won seven of the 10 stages, including the final day from Girardot back to Bogota which he won by eight minutes. His overall lead was 2 hours and 20 minutes, an astonishing margin of victory which has never been repeated.

Bogota was in a frenzy. El Tiempo, which had sponsored the race, estimated that 150,000 people turned out to greet the returning heroes. The police were unable to control the crowds, the city was paralysed and the riders were showered with gifts, large and small. The ‘Millionaires’ sporting club had a collection and presentation for the formidable Sara Trivino, Forero’s mother. The “London tailor shop” offered a shirt of English cloth to the rider who came last. El Tiempo announced the El Tiempo trophy, made of silver, to be presented annually to the winner of the Vuelta.

Credit was widely shared. The riders and their families, their sponsors, regions, the radio stations and newspapers, all congratulated each other and all were congratulated. And so in just two weeks, the Vuelta a Colombia was created and the people of Colombia took her into their hearts.

Promoted and feted by the social media of the day (the newspapers and the radio stations), cycling quickly became the national sport. A year later, for example, a “sportive” from Bogota to Facatativa and back attracted 1,135 amateur cyclists, including 25 from the national police. On the same day, there was an international meeting at Bogota’s Velodrome featuring a world class field.

Colombia had fallen in love with cycling, and with the Vuelta a Colombia in particular.

THE BIG CLIMB: how the world's toughest road race created a nation of cycling superstars by Stephen Norman is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments