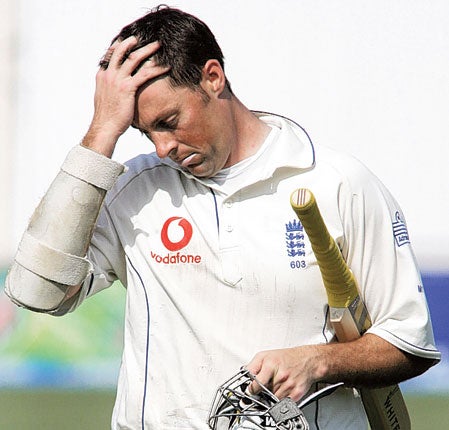

One more victim of modern cricket's constant demands

Mike Yardy's issues show it's time the game took a serious look at a calendar that asks so much of players

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The most illustrious cricket depressive of recent years is Marcus Trescothick. His international career was cut dramatically and cruelly short in 2006 by the curse of the illness from which he had suffered for most of his life.

Trescothick wrote a moving book about his ordeal, Coming Back to Me, which was both cathartic and award-winning but he has never been able to resume his rightful place in the England batting order. Had he been able to overcome his affliction, Trescothick would be in Colombo now, preparing to open for England in the World Cup quarter-final tomorrow.

Mike Yardy's illness may differ in its precise nature – for depression comes in many forms and will affect one in four people at some juncture in their lives – but it may be no accident that both men are cricketers who are required to spend unconscionably long periods away from home. Trescothick seemed somehow to have found a method of coping. Although it was patently clear that he found long tours arduous – and averaged 51 per innings at home, 36 away – he managed for a while.

In his book he indicates that what might have finally proved too much for him was an incident at home in which his father-in-law was injured and taken to hospital seriously hurt. Instead of going home to be with his wife, Trescothick was persuaded to stay. But he felt he knew where he ought to have been and never came to terms with his decision. That was in Pakistan in late 2005 and it was early on the tour of India three months later that his torment grew so great that he went home, never to play again for England abroad.

It is unlikely that going on cricket tours is the cause of depression but they have the capacity to exacerbate it. Geoffrey Boycott's embarrassing interview on BBC Radio yesterday demonstrated that there is still some way to go in convincing many people of that, including those who, like Boycott, have been touring for almost 50 years.

"I'm surprised, very surprised," Boycott told the 5 Live Breakfast Show. "But he must have been reading my comments about his bowling, it must have upset him. Obviously it was too much for him at this level. If any blame is attached it's partly to the selectors because I'm sorry, he's not good enough at this level." Yardy is neither the champion cricketer that Boycott was, nor much more importantly, the prize prat that he sometimes is, but he has made the most of his talents and he was a significant part of England's team when they won the World Twenty20 last year.

Boycott's crass inability to grasp the issue merely clouds it when trying to assess how cricket tours can affect depression and whether too much is expected of the modern cricketer. Many of England's players have been away since late October, some of them spending only three or four days at home between the Australian tour and the World Cup. Yardy was not part of the initial squad in Australia for the Ashes but he was playing in New Zealand. He did not go for the money – there would be scant little of that – he went because he wanted to prepare as thoroughly as possible for the biggest one-day tournament in cricket.

But it has taken its toll, as Sussex, the county of which he is captain, seemed to imply yesterday when they said he had been away for nearly five months and now asked for privacy while he spent time with his family. At least Yardy was being asked to peak only once this winter, for the World Cup. Ten of the cricketers in the original squad here were being asked to do so twice, first in the Ashes, the greatest prize in English cricket, and then in the World Cup. It is an onerous business, finding the rarefied level of performance to win in sport.

Players are well aware that their career is short and that they jolly well ought to make the most of it while they can. The rewards for being an England cricketer have never been higher.

Naturally, many of them are at that time of life when their wives are having babies and they are becoming fathers. The fast bowler Jimmy Anderson's wife gave birth to their second child and Anderson was twice allowed home between matches to see his family. Yet during England's match in Chittagong the other day, when the match was slipping away, Anderson aged as if the portrait of Dorian Gray was being unveiled before our eyes. He was without doubt mentally shot, a phrase used privately by some in the team management.

Graeme Swann, a different individual altogether, was home for the birth of his son, Wilfred, between the Australian campaign and this one. And that was that. His paternity leave has been spent trying to get enough purchase on the ball to take England to the World Cup final. He has shown no outward signs of malaise and his Twitter contributions remain as vibrant as ever but he would not be human if he did not prefer to be home.

This article is being written in the confines of a well-appointed hotel room, the 21st that this reporter has stayed in this winter (two, maybe three, to go). Some have not been so well-appointed. Hotel rooms drive players crazy eventually, they drive reporters crazy and anybody who says that you both have the best jobs in the world – and we all know it, we can never forget it – should remember Mike Yardy and the players to come, for whom they are not all days of wine and roses.

Cricketers who have suffered with mental illness

David Bairstow

Represented England in four Tests and 21 one-day internationals. In 459 first-class games for Yorkshire he took 961 catches and 138 stumpings. Committed suicide in 1997.

Phil Tufnell

Took 121 Test wickets for England but trouble with his private life saw him taken to – and escape from – an Australian psychiatric hospital in 1994

Graham Thorpe

One of England's finest batsmen, Thorpe suffered marital problems that made touring a strain for him. He pulled out of two England touring squads before departure.

Marcus Trescothick

England's 12th highest Test run-scorer suffered a stress-related illness on the 2006 tour of India and struggled to regain a foothold in the side.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments