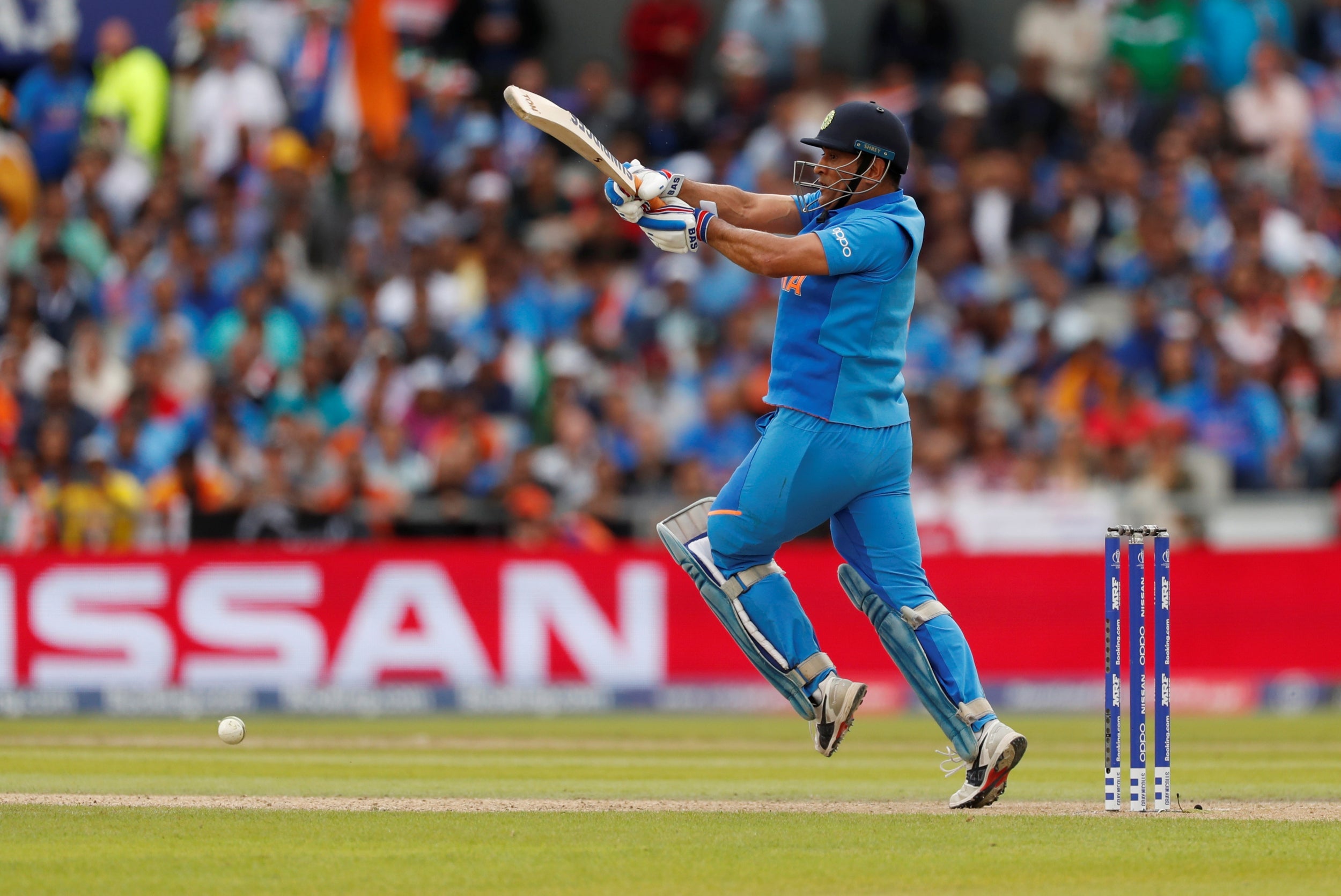

How MS Dhoni broke free of cricket’s shackles to transcend India itself

A future in politics may not be much beyond India’s great captain after retiring from the international game, but we know for certain it will be on his terms and within his control

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It tells you a lot about Mahendra Singh Dhoni, the person and the cricketer, that his closest friends who grew up with him in Ranchi, India’s fourth city – and whose counsel he still keeps – had no idea.

Following an Instagram post that appeared at 3pm on Sunday – “Thanks… Thanks a lot for ur love and support throughout.from 1929 hrs consider me as Retired” – a couple of his friends were contacted by journalists following up the underwhelming international retirement of India’s most inspiring personality.

Both laughed it off, reassuring the person at the other end of the line that it must have been a hack. Moments later, calls were returned with confirmation that was previously unfathomable along with the reminder that, when it comes to Dhoni, there are even seismic things those who know him best aren’t sure of.

That’s how Dhoni has always wanted it. Public and private life kept apart, and all within his control: cricket was his most front-facing side and was a vehicle for him to transcend not just the sport but Indian culture itself.

But it was his extra-curricular interests that always fascinated. He likes motorbikes, he likes his guns, and greater than both is his fascination with the military. In 2011, he was awarded honorary rank in the Indian Territorial Army and, in 2015, became a qualified paratrooper after five training jumps at a training camp in Agra. During India’s first match of the 2019 World Cup, Dhoni wore the insignia of the forces on his gloves. He was told by the ICC to remove it, much to the ire of the BCCI and the rest of India.

None of that would matter, of course, without his cricket – particularly his accomplishments as captain. Even then, a World Twenty20 title (2007), a No 1 Test ranking (2010) and 50-over World Cup (2011) followed by the Champions Trophy in 2013 – were achieved by turning the role into something that would work for him.

Captaining the India side is one of the toughest gigs in international sport and analogous to reaching a high-ranking government position in that it requires a great deal of politicking and at some point, compromising your values. Dhoni, somehow, avoided both when he was assigned the post in limited-overs cricket from 2007 before assuming it across all three forms the following year.

So he did with it what he wanted, which was always what was best for India. When there were calls from traditionalists to ditch the rockstar locks, which came down past his ears and were unbecoming of a leader, he grew them out to touch his shoulders. And that’s generally how he went on to approach any kind of criticism of his selection or tactics.

The ambivalence would serve him well, even when it fell flat. After the West Indies defeated India in the 2016 World T20, Dhoni walked into his post-match press conference at the Wankhede Stadium in Mumbai with a pre-rehearsed bit.

Knowing he would be asked about his future as captain, he planned to get the journalist, who he assumed would be Indian, to come and sit with him in front of the cameras and ask if they had a son that was ready to keep wicket for India. The answer was likely to be “no”, at which point Dhoni would shrug and suggest he keep at it. The room would fall about laughing and from bitter disappointment comes feel-good fodder for the news cycle.

Only, the journalist who asked the question was not Indian, but an Australian working for Cricket Australia’s media team. Upon calling him up, Dhoni broke character, offering, “Ah, this would work better if you were Indian.” Still, he cracked on and achieved the desired result.

His batting was similar. Hardly traditional but remarkably effective. The “helicopter shot”, a whirlwind of forearms and wrists to heave the ball over the leg side for six created a fear among bowlers that kept working for him well beyond his outright powers. Because, really, he was not much of a risk-taker, this was just the image.

It’s because of Dhoni’s calm and control that nobody has finished winning ODI chases unbeaten more times than him, and only four players worth their salt in the format average better than his 73.66 against spin, which requires the most risk to score against. His career-defining innings of 91 not out against Sri Lanka in 2011’s World Cup Final was the perfect wedding of both. Even though he did not take the limelight away from Sachin Tendulkar that night in Mumbai, he gave us a marker of just how big he was and how much bigger he would become.

Even just off the field, Dhoni was a master at doing right by his team. He could deal with the suffocating nature of fandom and the glare of the media but knew it affected others more. So he would bring players under his wing to guide them, even at Chennai Super Kings, his Indian Premier League franchise.

Dhoni understood his aura was something others fed off but knew he only owed people so much. For instance, in the last few years of his career, he would only stop for selfies with children. To grant them all would be an endless task, so why not save himself from the ones who need him most? But really it was out in the middle where the rest of us got the full scope of his genius.

When he empowered Joginder Sharma to bowl the final over of a 2007 T20 final, it went on to change the sport forever. There were smaller moments too that spoke of his craft: like at the death of a group match against Bangladesh in 2016’s World T20 when he sprinted for a run out at the striker’s end. Or the countless times he would be at the stumps distracting a batsman with some idle chat and use the arm they could not see to move a fielder in the deep. Moreover, there were not many as good standing up to the stumps.

Even when it didn’t go right, his legend grew, such as last summer’s World Cup semi-final against New Zealand, when he was run out for the eighth wicket coming for a second that would have still left 23 to get from nine deliveries with the tail. Only then did New Zealand truly feel at ease. “You would probably have still backed him with 18 needed off the last six,” remarked one player who was on the field at the time. Even though Dhoni by then was supposedly a spent force.

That would end up being his last match in Indian colours. After 90 Tests, 350 ODIs, 98 T20is and over 17,000 international runs, he was done.

Dhoni will still lead Chennai Super Kings in the tournament that now dominates world cricket, even during a global pandemic. His influence more broadly will continue, not simply within Indian cricket but India as a whole.

He will now spend more time with the Territorial Army and continue to be a presence for what is now a proud, nationalistic county. And he will continue to cultivate a vision of India that does not forget their past, but moves forward by using it as fuel.

It was no coincidence he chose Independence Day to step away from “international duty” in its most trivial sense. A future in politics may not be much beyond him, but we know for certain it will be on his terms and within his control.

That is why, to step back from cricket, he is more than the two greats he shares the modern podium with. Tendulkar wanted to simply "be", and grew to be a god of the game. Kohli wanted to live and became its first global megastar. But Dhoni wanted to be himself and break free of its shackles, and for all the admiration those first two have, they will both envy what Dhoni made of himself from similar opportunities.

Young cricketers want to grow to become Tendulkar or Kohli. But young India aspires to be MS Dhoni.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments