James Lawton: Heavy weight of blame for cricket – and a crying shame for brilliant talent

Everyone agreed that the crisis was not most about a teenager from Pakistan but the integrity of a game that rarely, if ever, had been so badly served

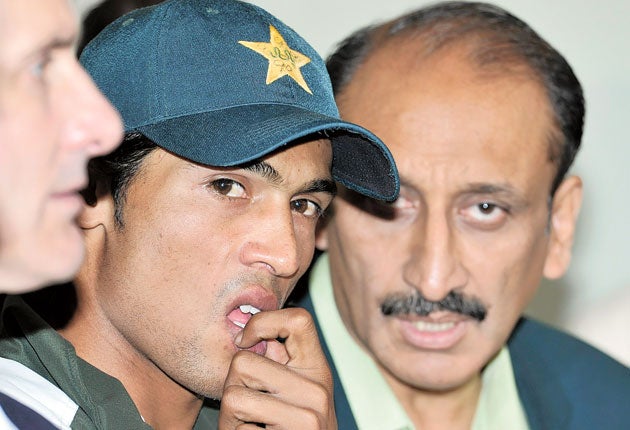

When the great baseball player Shoeless Joe Jackson went into court to answer for his part in the Chicago "Black Sox" World Series scandal of 1919, a street urchin was said to have pushed through the crowd and shouted: "Say it ain't so, Joe." There was no such cry yesterday when Mohammad Aamer carried his bat through the Lord's Long Room and then later stood, as though he was suddenly occupying an alien planet, before being presented with his reward for being Pakistan's man of the Test series.

There were several reasons for this. One was that Jackson had had plenty of time to create his heroic aura. He was 32 when his world collapsed. Aamer is 18 and before he too became ensnared in a betting scandal that will mark him for ever he had just a few opportunities to announce that he had the potential to be one of the greatest bowlers cricket has ever seen.

Another explanation was that cricket followers have for some time been aware of the possibilities of match-fixing and the fall of Aamer was thus something to be suffered more with sad resignation than burning regret and disbelief. Still, despite the age differences, there was something Jackson and Aamer had in common when they contemplated the scale of their self-destruction. Both had grown up dirt poor. Aamer lived in a boys' home from the age of 14 and suffered a potentially fatal virus attack. Jackson was the son of an itinerant share cropper in South Carolina and by the age of six was putting in 12-hour shifts at the local textile mill. He was a "linthead", a kid who kept the dust down on the mill floor.

It was difficult to get the sadness of the Jackson story out of your mind here yesterday. He had no education, certainly no more than today's casualty, and because he was illiterate he was obliged to wait for his team-mates to make their orders when they went out to dinner then echo one of their choices. Later, the value of his sports memorabilia was much reduced by the fact that he generally asked his wife to sign his autograph.

None of the parallels in these stories is likely to persuade the cricket authorities to show mercy towards Aamer if it is proved that he, along with the young captain Salman Butt and team-mates Mohammad Asif and Kamran Akmal, were involved in the organising of a betting coup. Nor, perhaps, should cricket display leniency.

However, this did nothing to soften the pain of witnessing a young boy of the most beguiling talent and apparently sunny nature making what might just prove to be his last strides in a theatre of sport he had come to command so brilliantly, so quickly.

Assuming that Aamer's name goes up on the Lord's honours board after his astonishing haul of five front-line English wickets, and the not inconsiderable scalp of Graeme Swann, last Friday, we can only hope there will be difficulty in explaining to some future generation of cricketers how it was that such talent was banished from the game at such an early age.

Difficult because cricket had learnt in the intervening years some powerful lessons from an episode that shamed it to its core. Cricket surely carried a heavy weight of shame yesterday. Certainly, some of it belonged to the game of Aamer's native country. Perhaps some more also had to be attached to the lack of care with which the world-wide authority has presided over the rush of wealth which has been heaped on the game, especially with the surge of popularity for the crowd-pleasing Twenty20.

We might now wonder how it is that if the great Wasim Akram was a significant patron of Aamer's talent, brow-beating the Pakistan board into an understanding of its power and depth, the nurturing of the young star has subsequently been marked by such negligence.

It is a nightmarish story told by the News of the World investigation team and among all the sickening detail we had the haunting incident of the alleged "fixer" calling up the sleeping boy cricketer in his room, addressing him as "fucker", and then deciding that the "instructions" could wait until the morning. The object of such treatment is an 18-year-old who in the last seven weeks has played six Tests matches, two against Australia and four with England. In the circumstances it was maybe understandable here yesterday there was no marked rush to judgement, neither in the ground nor those corners where the sizeable detachment of great former players discuss the current standing and performance of the game they played with distinction.

One of them said: "We all know corruption goes on the game but it is not so easy to prove, not in a court of law, which is where you have to do it in the end if you are going to get some meaningful action. Still, what we're looking at here is not so much a scandal as a tragedy. You looked at this kid Mohammad Aamer and you had to ask: "what can go wrong? He's a natural". We know now. What can go wrong is a lack of care, too many people who are interested in making money rather than making the game better."

Shoeless Joe protested his innocence vehemently but never played major league baseball again. He appeared in the semi-professional leagues, a diamond in the small-town dust, and he ended his days running a liquor store back in his hometown. That will not be an option for Mohammad Aamer back in Pakistan. So what will become of him? Will he too be required to provide some odd flashes of what he once was, however briefly, on some rough field?

It was a terrible possibility on a day when the wind can never have so blown so coldly through the old battlements of Lord's. Everyone agreed that the crisis was not most about a teenager from Pakistan but the integrity of a game that rarely, if ever, had been so badly served. However, it was impossible not to be pained by the fact that nobody had been around to cry, rather like the boy on the streets of Chicago, "Say no, Mo." If things turn out as badly as they might for Mohammad Aamer, that will be something more than a single regret. It will be a reproach to all of cricket.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments