As England's seamers thrive at Trent Bridge, a NASA expert explains why swing bowling isn't rocket science

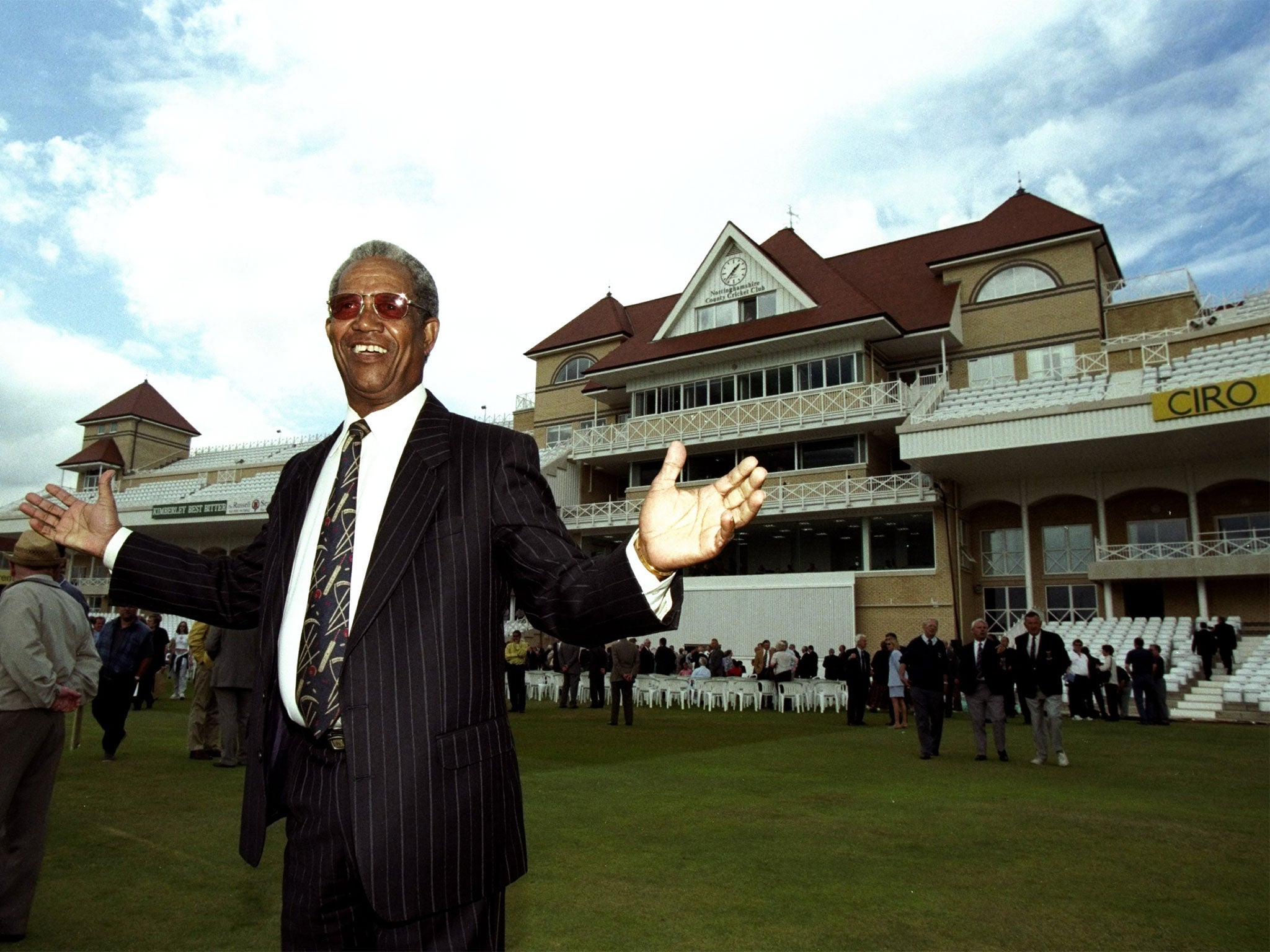

Rabi Mehta, an aerodynamics expert, talks Richard Edwards through the science of swing

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Jimmy Anderson returned to his favourite stomping ground this week – a venue where he had taken, before the current Test, 53 wickets, including six five wicket hauls, at a cost if just 19.

It was also the ground on which he scored 81, the highest score by an England number 11 in history, in a world record tenth wicket partnership with Joe Root against India in 2014.

There have been various theories as to why Anderson boasts such a successful record in Nottingham.

One is the presence of the Radcliffe Road Stand, which was built in 1998. A building which, according to some, has reduced the circulation of air at the venue. Others suggest that Trent Bridge’s lush, green outfield plays a part in keeping the ball in pristine nick for Anderson to swing it round corners. Or at least past flailing bats.

It’s easy to give credence to both, given that no other England bowler in history has taken as many wickets at a ground which hosted its first Test in 1899.

Mention those Trent Bridge theories to Rabi Mehta, a world-renowned aerodynamics experts and a real-life rocket scientist with NASA, and a smile appears across his face. Even at 6.30am in California.

“The key is that he can release the ball perfectly – there are few players in the world today, who can release the ball with the seam angled perfectly and that seam not wobbling at all,” he tells Independent Sport.

“He can do that and that’s why his out-swinger is so successful. That’s the key. Initially, he didn’t swing the ball, he was just encouraged to bowl fast. It wasn’t until his mid-20s that he really began swinging the ball regularly.

“It’s all in the technique. When the ball leaves his hand he has the seam angled, at 20 degrees or so, and the seam is steady in its rotations. If you do that then the ball, and particularly a new ball, will swing on any ground and in any conditions.”

In an England career now entering its 15th year, Anderson has proved himself to be a modern master of his trade, taking 470 wickets, not through pace but through an ability to move the ball, sometimes seemingly at will, against the world’s best batsmen.

His 2013 performance against Australia cemented his special relationship with the ground. In a pulsating first Test of the series, Anderson took 10 for 158 in the match, including the game-sealing wicket of Brad Haddin, snared by Matt Prior behind the stumps with the Aussies just 14 short of victory.

It was an off-cutter that eventually did for the Aussie wicketkeeper but it was a display of devastating swing bowling in the Nottingham sun that put England in a position where they could push for the win.

Mehta, a global expert in aerodynamics, worked with the ECB on an instructional video on swing bowling, which involved Anderson, back in 2015. During that video, the Lancastrian himself admitted that swing bowling still maintained an air of mystery – even to a bowler widely-acknowledged to be one of its greatest exponents.

“There have been days when the sun is out and the ball swings and some days when it is freezing cold at the end of April and it swings. I couldn’t tell you when it is going to swing, NO!” said a bowler who is now closing in fast on his 500th Test wicket.

Mehta, though, is convinced that science does have the answer, even to so-called reverse swing, which is another subject entirely.

“There is no special grip for reverse swing – if you can swing the ball then you can reverse it, according to the condition of the ball,” says Mehta.

“A ground can make a difference if there is a predominant wind direction. If you take Hove as an example, you often have the wind coming off the sea. That’s pretty well known. Again, though, in terms of the science, I can’t see what’s so special about Trent Bridge.

“I also can’t say that a cloudy, humid day will guarantee swing. A lot of this is ingrained in the mind of cricket players from when they first grab a bat and a ball at the age of five or six. You’re told that over and over but, generally, it’s just a placebo effect.

“I guess if you’re Jimmy and you’ve taken wickets at Trent Bridge before then you’re naturally going to be more confident than you would be playing somewhere else. You’re immediately focusing on the swing, rather than trying to bowl fast.

“Look at the 2007 World Cup final. You had Chaminda Vaas of Sri Lanka, a superb swing bowler, bowling against Australia in Barbados. He couldn’t swing the ball to save his life against the Aussies. I met the coach later that year and he told me that Vaas was trying to hard because his history against the openers (Adam Gilchrist and Matthew Hayden) wasn’t good.

“In that same World Cup final, Nathan Bracken, the Aussie opening bowler was swinging the ball happily. It was the same ground, same conditions, same weather, but one swing bowler couldn’t move it off the straight and the other could.”

So despite the theories about humidity and air currents, swing bowling isn’t rocket science at all. It just takes a rocket scientist to prove it.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments