In a week of English sporting prayers, let us not forget the ephemeral glory of Randolph Turpin

It is fitting to remember Turpin’s victory over Sugar Ray Robinson in this most delirious of weeks, a dramatic fight that belonged somewhere beyond the sporting rainbow of hope and wild dreams

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In a week of sporting prayers it is worth remembering that the glory lasted just 64 days for poor Randolph Turpin after the miracle of Earl’s Court on 10 July, 1951.

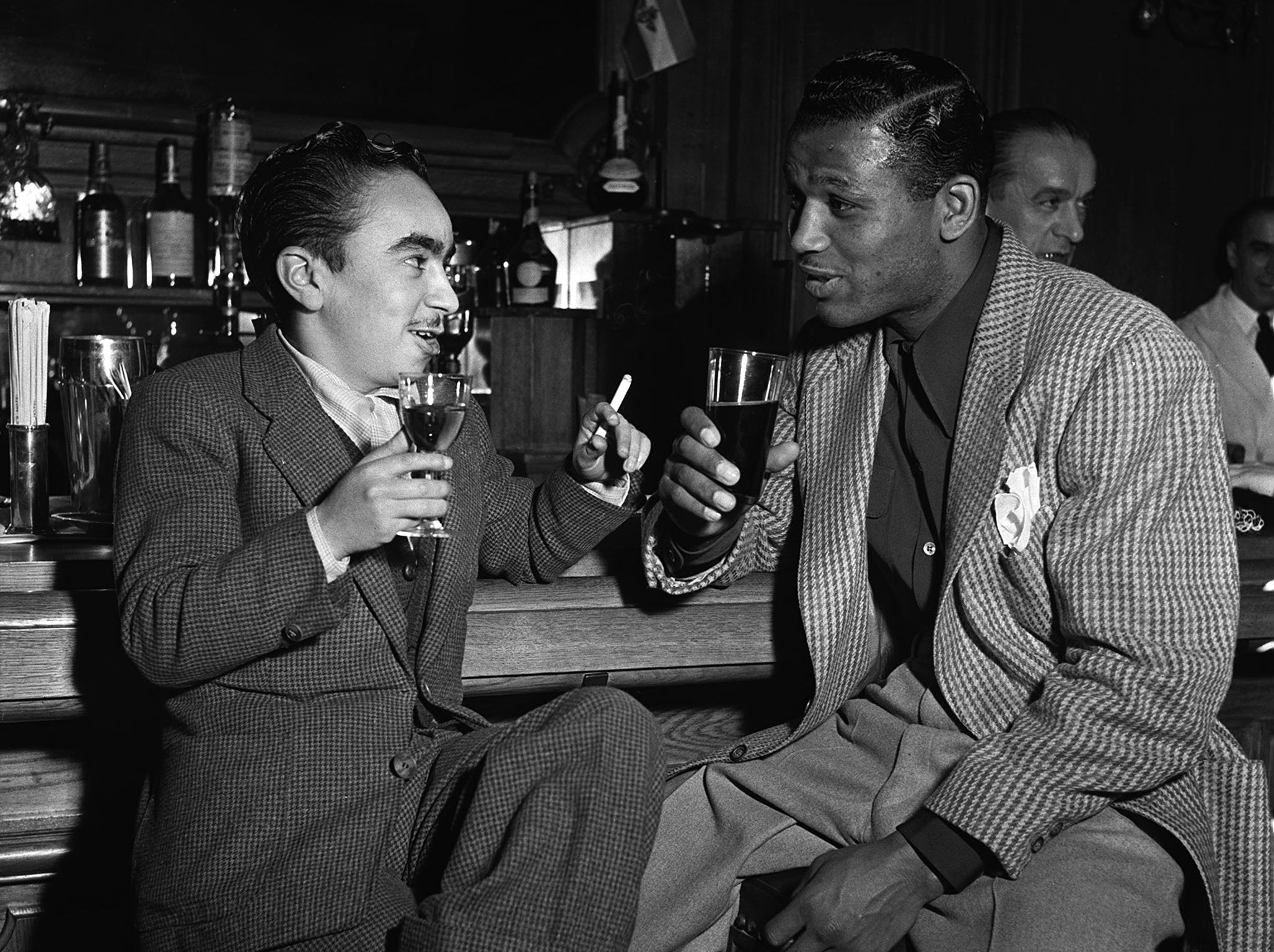

In that great summer of sport the legendary Sugar Ray Robinson toured Europe with 100 stacked suitcases, a dance instructor, a golf professional to help with his swing, a personal barber to keep the kink from his hair, assorted trainers and the Arabian Knight, a man called Jimmy Karoubi, who was just 36-inches tall in his silk socks.

“The Arabian Knight is not just a dwarf,” Robinson told the British press. “He’s a North African circus-trained dwarf.” He had his own tiny monogrammed livery.

The Robinson party were politely declined accommodation in London’s West End and settled for the boxing pub, the Star and Garter in Windsor, where Robinson created an exotic world in the week of the fight. In Harlem, New York, where Robinson was building his real empire he parked his ship-like pink convertible outside his shops, his bar and was constantly surrounded by people, his own zoot-suited force of men in splendid colours. Ray, you see, loved his people and when he went on a seven-city European tour - with seven fights in less than seven weeks between May and July 1951 - he took his own carnival: He was his own beautiful carnival.

Robinson was also, in early July 1951, the middleweight champion of the world, with just one loss in 132 fights. He had also been the untouchable welterweight champion of the world. He was 40 and zero in wins before the only loss on his record, on points to Jake LaMotta in 1943; in February 1951 Robinson stopped LaMotta in round 13 of what is now known as boxing’s own St.Valentine’s Massacre one bloody night in Chicago to win the middleweight crown. The fight with Turpin was the first defence of the title, an easy night in another starlit city.

Robinson won fights in Paris, Zurich, Antwerp, Liege, Berlin and Turin before meeting Turpin. The fight in Turin was just nine days before the title fight at Earl’s Court, a harsh reminder of just how different the fight game was; Robinson actually had 15 fights in eight months, including two world title fights during this period.

After the May fight in Paris, where he also fought in November and December of 1950, Robinson handed over his entire purse to the President’s wife for her charity and the Black Angel, as he was known in France, lived an opulent life in the indulgent city at a time when black American acts dominated the clubs. In Turin, the mean side of Robinson was glimpsed when he beat Cyrille Delannoit in three brutal rounds; it looked like Sugar was finally getting his fight-head ready. “I don’t like watching encounters like this,” wrote Peter Wilson in the Daily Mirror. “It makes me feel like an accessory to murder.”

The next day Robinson, his 100 suitcases, his dwarf and his barber made their way to London.

It was in Paris one afternoon at a suite of rooms in one of the city’s grand hotels that British boxing promoter, Jack Solomons, met with Robinson to pitch the Turpin fight. Robinson, surrounded by his heavily coiffured retinue, was offered 28,000 pounds, accepted straight away and a date was set. Solomons returned, made contact with Turpin and then sold every single one of the 18,000 tickets. Turpin, let’s be fair, had no chance.

“Timing, speed, reflexes - Sugar Ray Robinson was beautiful. The greatest fighter ever,” Muhammad Ali said. After the Rome Olympics in 1960 Ali wanted Robinson to manage him, in 1951 Robinson was a sporting idol, a special icon to black Americans of all ages. “Ray was like a black Clark Gable - there will never be another fighter like him,” said Reg Gutteridge, a ringside writer on the night.

Turpin was just a kid of 23 from Leamington, the British and European champion at middleweight. However, he was not a sacrifice, his manger George Middleton was convinced Robinson had made a mistake, had not taken Turpin seriously. “I expect it to be over in six rounds,” said Middleton. When Robinson was asked about that prediction he genuinely thought Middleton meant that Turpin would be stopped inside six rounds. “I’d like it to be just one round,” said Sugar Ray one night as he lightly touched the piano keys with his golden hands in the swollen bar of the Star and Garter. “But they tell me Turpin won’t co-operate, so I guess that it won’t go more than 15 rounds.” The great Robinson was right.

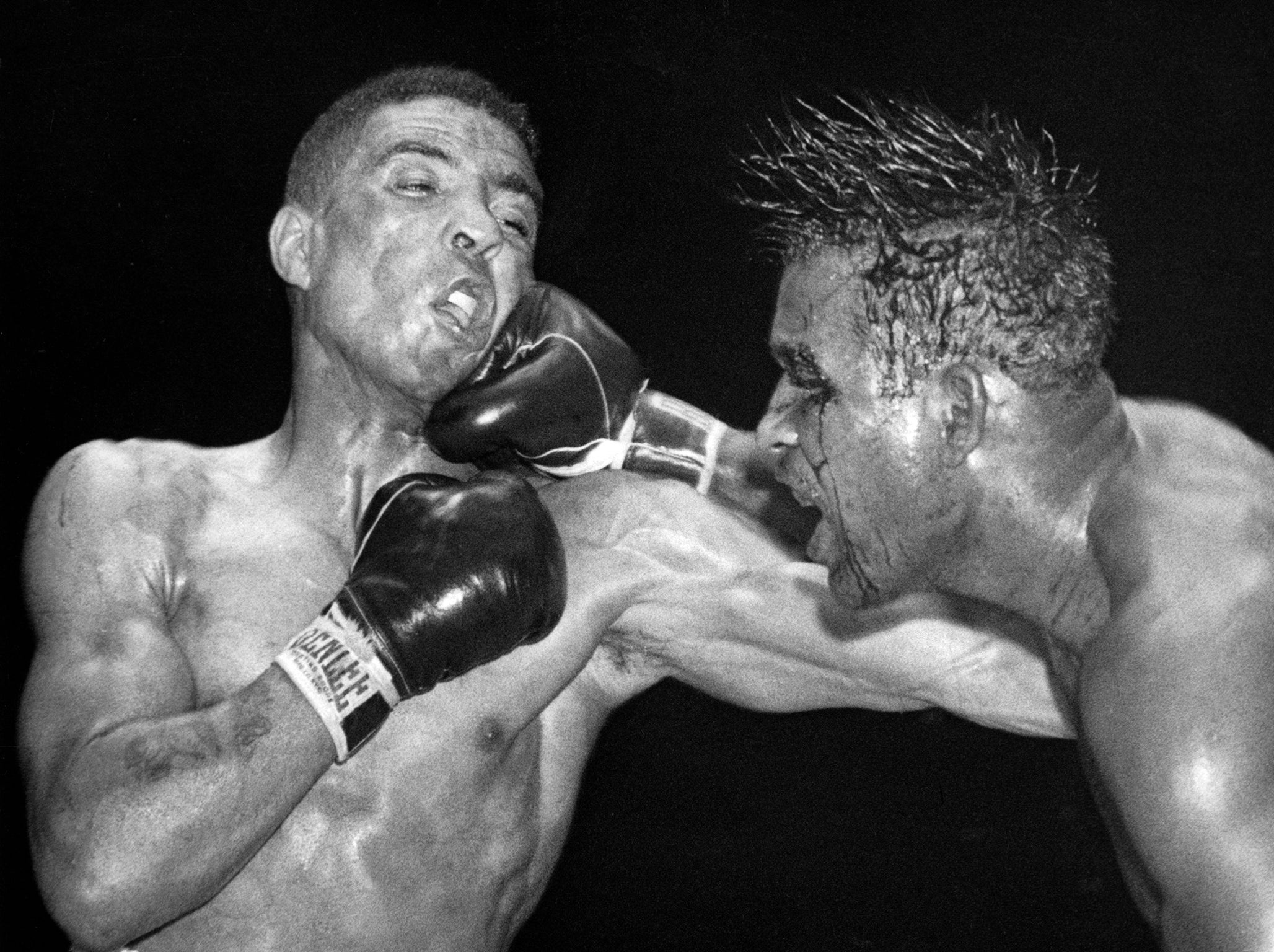

There was magic in the ring at Earl’s Court that night, wizardry from a relentless Turpin and Robinson was good, very good over the full fifteen rounds. They started singing For He’s A Jolly Good Fella, a chorus of the converted willing their man, the mad British underdog, through the last rounds. You can hear the hopeful harmony of 18,000 in the scratchy recording of the fight and it brings tears to anybody with a heart. At the end it was Randy’s hand that was raised, the new middleweight champion of the world and still the finest win by a British boxer.

The title was gone just 64-days later, Turpin stopped in round ten by Robinson in front of 61,370 at the Polo Grounds in New York. Robinson built his empire, fought until 1965 and died a miserable, lonely death in 1989.

Meanwhile, Turpin slowly lost control of a truly troubled life, mostly in public and forever under the inescapable glare that we permanently shine on our heroes. His suicide was in 1966, he was just 37, his finest night had been in 1951 in a fight somewhere beyond the sporting rainbow of hope and wild dreams. There is a lot of that going about this week.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments