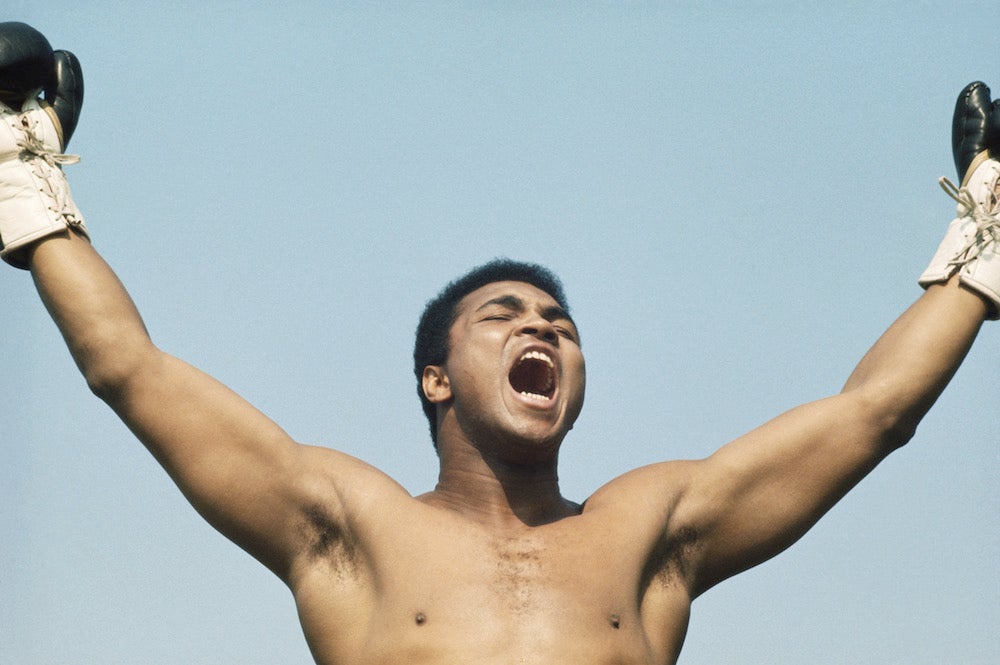

Muhammad Ali tribute: 'Greatest of All Time' loses his final fight

Muhammad Ali, the greatest heavyweight boxing champion of all time, has died at the age of 74

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.However long and severe the dimming of his light, the world was always going to be a darker place with the departure of Muhammad Ali.

Now that he has gone, after finally submitting to the ravages of disease and the punishment he took in the ring to which he brought so much courage and beauty, we can only begin to measure the depth of that old certainty. It is, indeed, the passing of a man for whom the finding of an adequate replacement has maybe never looked so remote.

No doubt we will always have phenomenal sportsmen; and, who knows, we might even unearth again a charismatic politician or two. But are they likely to enchant and madden and mesmerise in quite the fashion of the man who declared himself The Greatest?

Are they likely to stop the traffic in New York or London or Cairo if they happen to take a morning stroll?

How willingly would they step into the ring with a Sonny Liston or Joe Frazier or George Foreman – or the most powerful government in the world, as Ali did when defying enlistment for Vietnam on the grounds that he had no quarrel with the Viet Cong?

He added, “I’m not going to Vietnam to help bomb brown people when black people back home in Louisville are being treated like dogs.”

That stand cost Ali three and half years of the prime of his fighting life, and when he came back to meet the tough white American Jerry Quarry the Ku Klux Klan was mobilised and there were rednecks firing guns in the pine woods surrounding his Georgian training camp

They would not, however, have significantly enhanced their puny intimidation had they hauled up heavy artillery.

It is now largely forgotten how low in regard the former Cassius Clay was once held by white America: how he was banished from a fast food restaurant in his home town of Louisville soon after winning gold in the Rome Olympics, and how severely he was chastised for his boastful, traitorous ways by the American media – not least by the hugely respected New York sportswriter Red Smith.

Ali wasn’t always an American hero, but soon enough he was the property of a bedazzled world. “I am the greatest,” he reflected, “and I said that before I knew I was.” It was, at the very least, the most extraordinary wish fulfilment, and when the fighting was over he also said: “I hated every minute of training but I said: ‘Don’t quit – suffer now and live the rest of your life as a champion.”

If he made one miscalculation through those tumultuous years when he engaged the rawest edge of American life – making his alliance with the Black Muslims and running the daily risk of assassination, while regularly confounding the laws of probability in the ring – it was the extent of the price he would pay for lingering too long in such an unforgiving workplace.

The cost was so many years of incapacitating illness and a relentless dwindling of the force of a remarkable and so often luminous personality. He died after a short stay in hospital, admitted for respiratory issues earlier this week, following a 32-year battle with Parkinson's disease.

Yet if the reality of Ali’s life eventually became an ordeal, and if the last of his four wives, Lonnie, was required to fulfil the role of the most attentive manager and nurse, all that the man had come to mean could never be obscured.

It was, in those formative years of unsurpassable drama, a miracle of re-invention and nerve. There were two Alis in the ring. There was the one who rode the astonishing athleticism and skill and bravura of his youth beyond obstacles which included the fearsome Liston and such formidable opponents as Zora Folley and Cleveland Williams – and there was the one who came after the long hiatus imposed by the American authorities.

The second Ali was less quick, less sublime; yet it was this one that stepped so far beyond the boundaries of his sport and who made his name synonymous with some of the most compelling reaches of the bravest nature.

His Frazier trilogy, ending with the victory in Manila which he claimed had brought both men close to death, explored the very edges of each man’s desire to fight and survive; and when, early in 2011, Ali fell perilously ill after travelling from his home in Arizona to the Philadelphia funeral of his great adversary, there was an almost unbearable poignancy in the fate of one warrior and the plight of the man with whom he would be so unbreakably linked in both life and death.

But it was the defeat of George Foreman in 1974, in a stadium built in a jungle clearing in Africa, that defined the second Ali, the man of ultimate resilience.

Later, in his training camp beside a wide-flowing river, Ali reflected that he had not only beaten Foreman against all odds, he had also invaded the imagination of the world. By then, though, that was merely confirmation of a long established colonisation.

Gene Kilroy was a young lawyer serving in the US army when he first met Ali at the Rome Olympics. It was a collision that shaped his life. With the brilliant trainer Angelo Dundee, Kilroy was one of just two white men who remained within the entourage at the height of Ali’s distrust of white America. He saw all of it first hand: the rise, and the slow descent into the shadowlands of the last 30 years of Ali’s life.

Near the end, Kilroy recalled a winter morning in 1973 when he walked through the streets of Manhattan after Ali’s victory in the second Frazier fight.

“He had everything back then, the timing, the touch, the skill and the people in the street went crazy. They blasted their horns, they came up to hug him. He was more than the champion – and of course he was always that – he was the king of the world. It is the way I will always remember him.”

That wasn’t so easy six years later at Caesar’s Palace in Las Vegas, when Ali, slimmed down, even beautified by the extensive use of diuretics, was brutally pounded by his former sparring partner Larry Holmes. It went on for 10 rounds and there were tears in the eyes of strong men.

They included trainer Angelo Dundee, who threw in the towel. The damage had been done some time earlier, and Ali had gone beyond the years when mere courage would do.

As the most inspiring fighter the world had ever seen, that was. His legacy as a superb creation of the human spirit had, of course, already been secured.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments