Cassius Clay vs Sonny Liston: The amazing night Muhammad Ali became champion of the world

On what would have been Muhammad Ali’s 78th birthday, Steve Bunce reflects on the night Cassius Clay announced himself on the world stage

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Seven thousand empty seats greeted the arrival of Cassius Clay in the ring for his world heavyweight championship fight against Sonny Liston at the Miami Convention Centre on 25 February 1964.

The bout had been in doubt after Clay’s ranting at the weigh-in and there was a rumour that it had been called off; it was not a big contest and only 8,000 attended. Clay was viewed warily, given no chance and Liston was, as George Whiting wrote in London’s Evening Standard: “America’s No 1 menace in the blood-bath trade.” It was also pouring with rain outside and the promoters were ready to take a bath.

Clay was 22, unbeaten, untested and Liston had called him a “n****r f****t”, dismissing his speed. Liston was dubbed the “big ugly bear” by Clay and his people. However, the champion’s malevolence and raw power seemed to put any hope of an upset way beyond the fists, dreams and loose tongue of young Clay. It would be a simple beating.

Liston had lost just once in 36 bouts and in successive fights had won and defended the world title against Floyd Patterson; he had needed just four minutes in total for both wins. Liston had also beaten the men nobody wanted to meet in Cleveland Williams, Niño Valdes, Eddie Machen, Roy Harris and Zora Folley. Clay, unbeaten in 19, had not met one of the leading contenders from the list of Liston’s victims, which seems shocking now and explains why in the build-up the fight was considered a flop. His credentials were flimsy; Clay was there because of his mouth. In the previous two fights before going to his slaughter against Liston he had been dropped by Henry Cooper and looked painfully short of ideas against the much smaller Doug Jones.

In the Clay camp Angelo Dundee, his devoted trainer, was convinced of victory if Clay could avoid Liston’s left jab. Sugar Ray Robinson insisted that Clay’s speed was the factor and that he would knock out Liston. Robinson, it was pointed out, had fought 174 times – and was ignored.

There was a mink parade on the night as Miami’s finest arrived to watch the massacre, smiling, smoking and sipping cocktails at ringside like guests at a wedding reception. There was clearly a sense of destruction in the air, a morbid fascination with the beating that Clay was expected to receive. Ten days earlier John Lennon had answered a question about the fight’s outcome and Liston’s chances with: “Oh, he’s going to kill the little wanker.”

Fresh from appearing on The Ed Sullivan Show, which launched their conquest of America, The Beatles had been at Liston’s gym for a publicity photograph but he had them thrown out; they reluctantly made their way across town to Dundee’s 5th St gym to meet Clay. They were not impressed, but there remains an iconic picture from the brief meeting of Clay landing a punch and knocking out the Fab Four.

“My guy knew he had to really fight to win that title,” Dundee said. “We had to move from the jab, not run and not do anything foolish. Make no mistake; it was never going to be easy.” Dundee was right, as usual, and he knew what we all know now: Clay was ready.

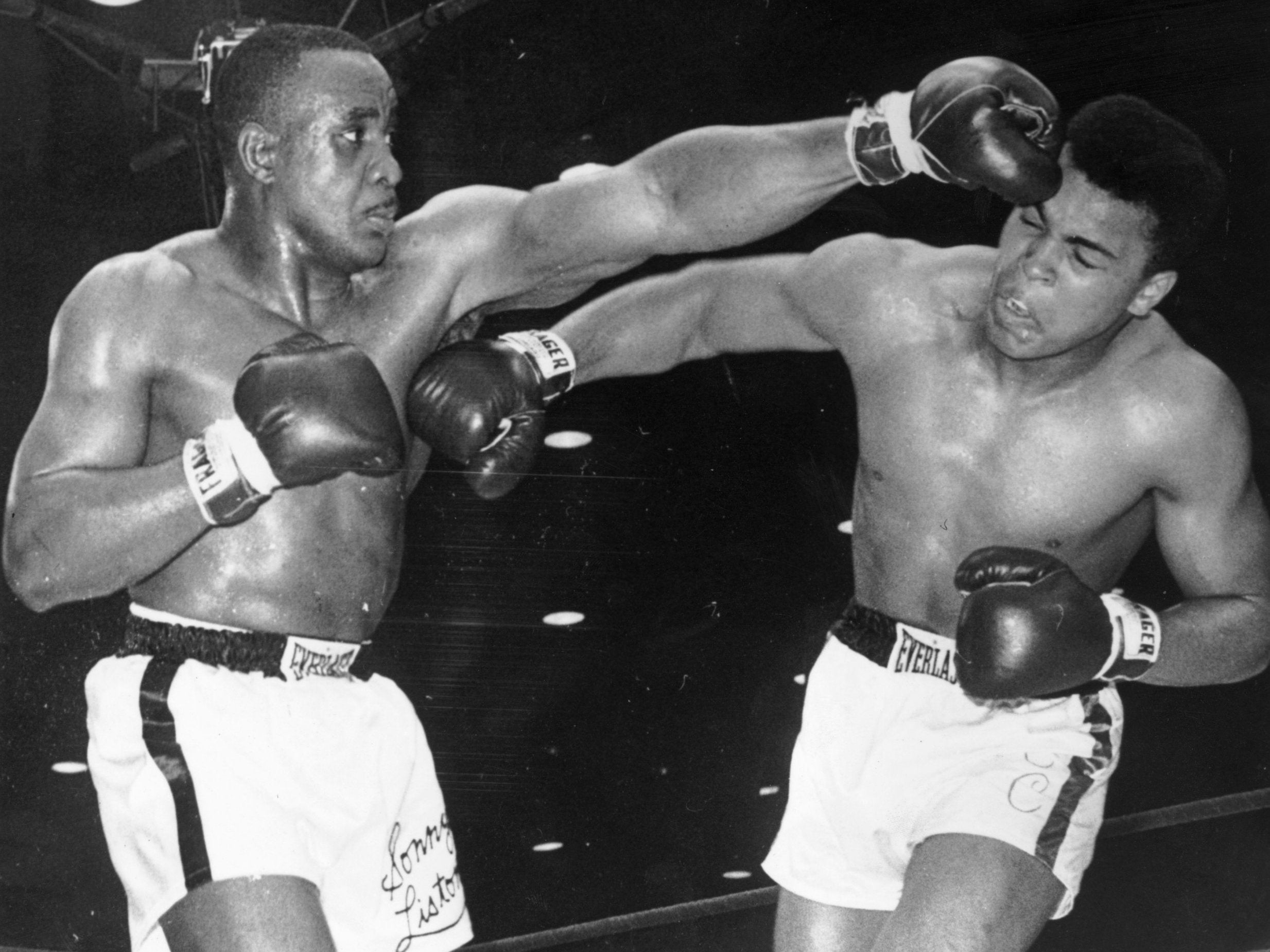

It was an amazing fight. Clay moved with sense from the opening bell and it was clear that Robinson was right about speed. Liston was slow, his jab wide, his thunderous rights landed in fresh air. In round three, Clay cut Liston under the left eye and the champion’s cuts man went to work for the first time in 11 years. Whiting wrote in wonderment: “The omnipotent Liston was, after all, subject to human ills under pugilistic assault.”

In round four Clay started to show signs of distress, dabbing at his eyes during the final seconds. At the bell he pleaded with Dundee to cut his gloves off – he could not see, he screamed – and in the confused 60-second interval the referee, Barney Felix, admitted he nearly stopped it. The theory is that some of the substance used to close Liston’s cut had somehow got in Clay’s eyes. However, Dundee had his finest moment right then in coaxing his man back into the centre of the ring, blinded, scared and nearly broken.

Round five was torrid; Liston’s last stand and at the bell the seemingly indestructible fighting man must have known it was nearly over. He fought the sixth, missed with most of his last punches as world heavyweight champion and then slumped into submission at the bell. The Big Ugly Bear stayed on his stool, spat out his gum shield and could not look up as Clay celebrated.

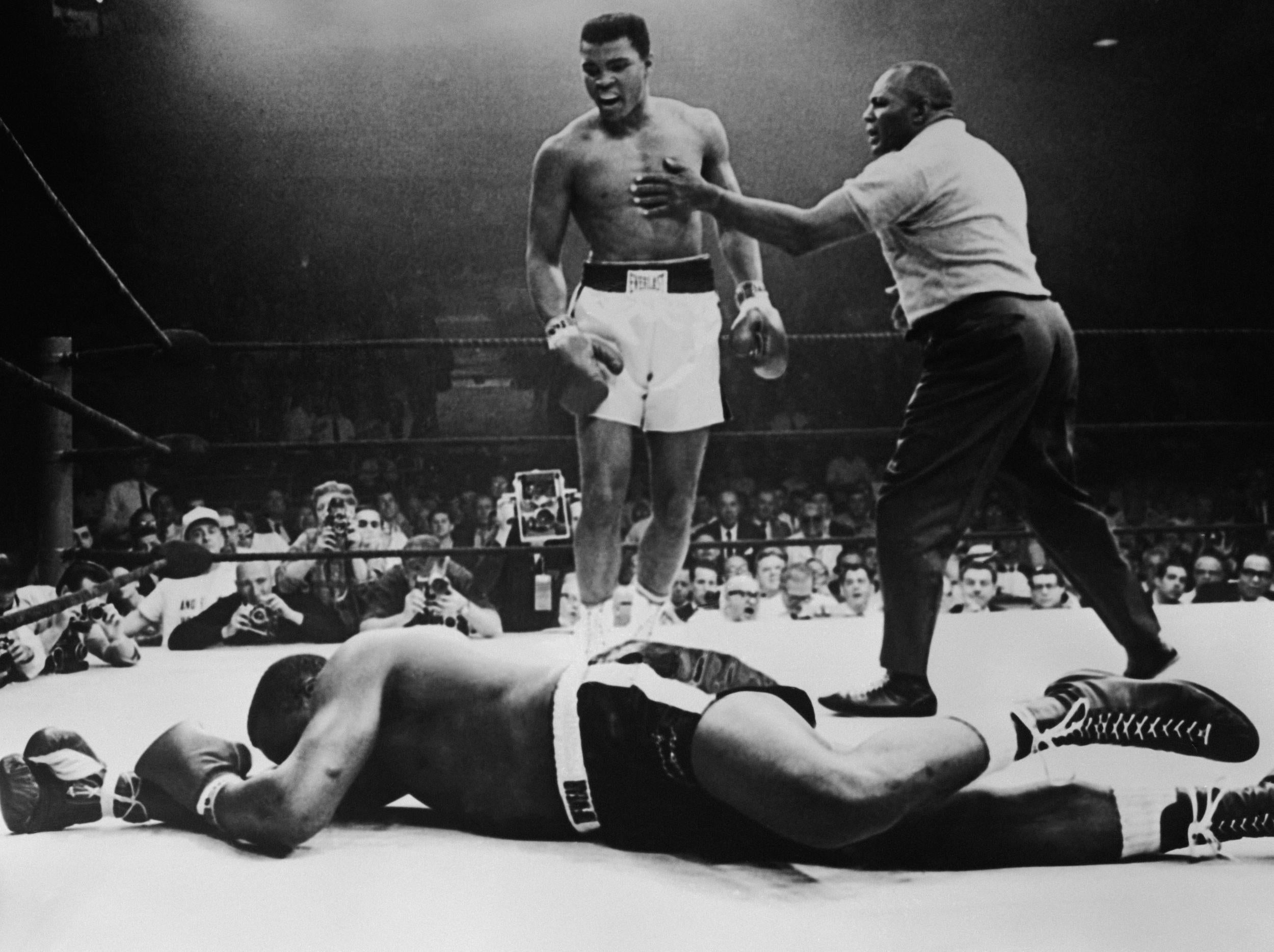

Liston had injured his left shoulder and X-rays and experts confirmed the damage but boxing often demands more than mere medical proof as a reason for quitting. They met again the following year and fewer than 2,500 showed to watch Liston dropped and stopped in the opening round.

So in Miami, Clay became champion, soon to become Muhammad Ali, and over time he evolved into the sport’s greatest fighter. That night he was just starting on the most incredible journey, and that old sentimental fool Whiting was right: “The horizon is his, and all of its rainbows.” Boxing was never the same again.

This article was first published on 24 February 2014

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments