Mickey Duff dead: He was the master of the ring – and the pithy putdown

Manager and promoter of household names has died at 84

Among the many attributes Mickey Duff brought to bear in a notable career as a boxing manager and promoter was his wit. His most celebrated quip is: “If you want loyalty, buy a dog.” That does a disservice to another of his mighty contributions to the boxing one-liner: “He couldn’t match the cheeks of his own backside.”

The pithy insult is central to the business of professional boxing, where a razor-sharp mind out of the ring is as effective as an uppercut in it. Duff was a master of the art of selling as well as making a fight. For a quarter of a century he was the face of a powerful cartel that dominated British boxing, a period when the sport shared top billing and its heroes were household names.

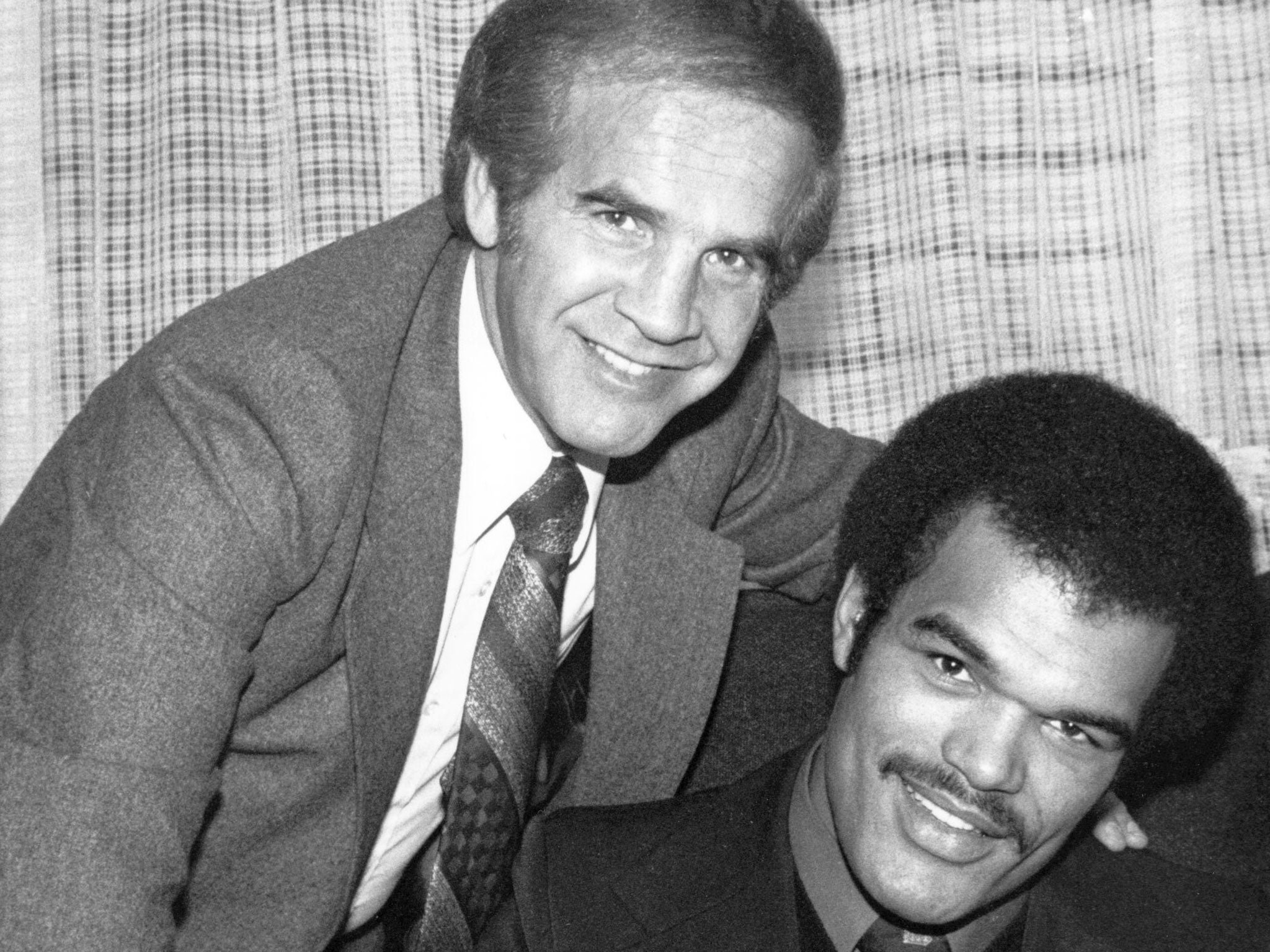

Duff’s broken features settled across his face like a jigsaw puzzle and were among the most recognisable in sport during the 1960s and 1970s, which may now be seen as a boxing golden age in these isles.

His career coincided with the rise of the phenomenon of televised sport. During a 33-year monopoly with the BBC he was associated with 50 world champions and more than 150 title fights.

Duff marched into our homes a succession of legendary figures whom we felt we knew in person: Terry Downes, John H Stracey, Charlie Magri, Alan Minter, John Conteh, Maurice Hope, Lloyd Honeyghan, John “the beast” Mugabi and, arguably the most famous of them all, Frank Bruno. To the music of Harry Carpenter’s inimitable commentary, we lived through every round at the Royal Albert Hall and Wembley.

Duff, the son of a Polish rabbi from Krakow, toiled through more than 60 bouts as a kid, and enjoyed a nice little sideline as a circus act with the travelling Billy Smart’s emporium. “When we were in Cambridge I was young Billy Jones of Cambridge, when we were in Oxford I was young Billy Jones of Oxford. I was always the local boy,” he once said. “The deal was the local guy had to last six rounds with the circus fighter to win the money. So I would come up and put up a good fight and the crowd would cheer, but it would always end up with me getting knocked out with about 10 seconds of the final round to go. We knew the crowd would be real proud of their ‘local boy’ for having a go, so we would pass the hat around afterwards and split that money too.”

This was the grounding Duff brought to the business side of boxing, using his powerful associations with Jarvis Astaire and Harry Levine to smash the hold on the sport held by Jack Solomons, just as Frank Warren would do to him with the advent of Sky Sports.

Duff was widely respected in the United States, where he turned down the chance to be match-maker at Madison Square Garden. He knew enough about the men in the ring to wager $200,000 on the Hagler-Leonard bout in 1981 and win: “At the time it was probably 30 per cent of all I possessed. Nowadays I occasionally go into a casino, lose £200 and run for my life.”

Hagler was so convinced he had won that he chose never to fight again; that’s how close it was, but Duff was sharp enough to split them.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments