Remembering Lou Duva - an irreplaceable man in an ancient business

The promoter died age 94 last week

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Lou Duva once beat Rocky Marciano in a meatball and spaghetti eating competition, he carried Floyd Patterson from the ring after a fight with Muhammad Ali and bleated, moaned and threw punches to defend his fighters.

Duva was 94 when he died last week after a life in the boxing business on both sides of the ropes and with Duva there was never a safe side of the ropes. In 1996 he was in the middle of an ugly melee in the ring when his fighter Andrew Golota was disqualified in a ridiculous brawl with Riddick Bowe at Madison Square Garden. Duva climbed through the ropes, Bowe's entourage did the same and there was an ugly verbal stand-off before the punches started to fly; Duva took a punch, threw a punch, had a heart attack and spent the night in hospital. Duva was 74 at the time.

"I've been fighting all my life," Duva said. "Look at this face. You think I got these looks being a ballet dancer?"

In the ‘50s, after a brief and disastrous career as a face-first boxer, Duva was a silent witness at Stillman's gym on Eighth Avenue in New York. He watched men like Ray Arcel and Whitey Bimstein work with their fighters, men from boxing's finest fights, and Duva just listened, learning a trade he loved. "There is an old Italian proverb," he said. "If you love what you're doing, you don't have to work a day in your life."

At the time Duva had opened a trucking company and was always in New York making deliveries. "I would sit and watch the great trainers and just sit and listen to them when they were talking," Duva said. Watching and listening are two of boxing's lost arts, both increasingly unnecessary in a modern sport dominated by instant success and anonymous strength and conditioning fools. Duva was one of the last remaining links with a history stretching back over one hundred years having sat at the knees of men born in the 1890s. He talked of Brown Bombers, Sugars, Rockys, Kid this and Kid that like a man reciting the contents page of a well-thumbed book, a book of wonder and fantasy to boxing fans.

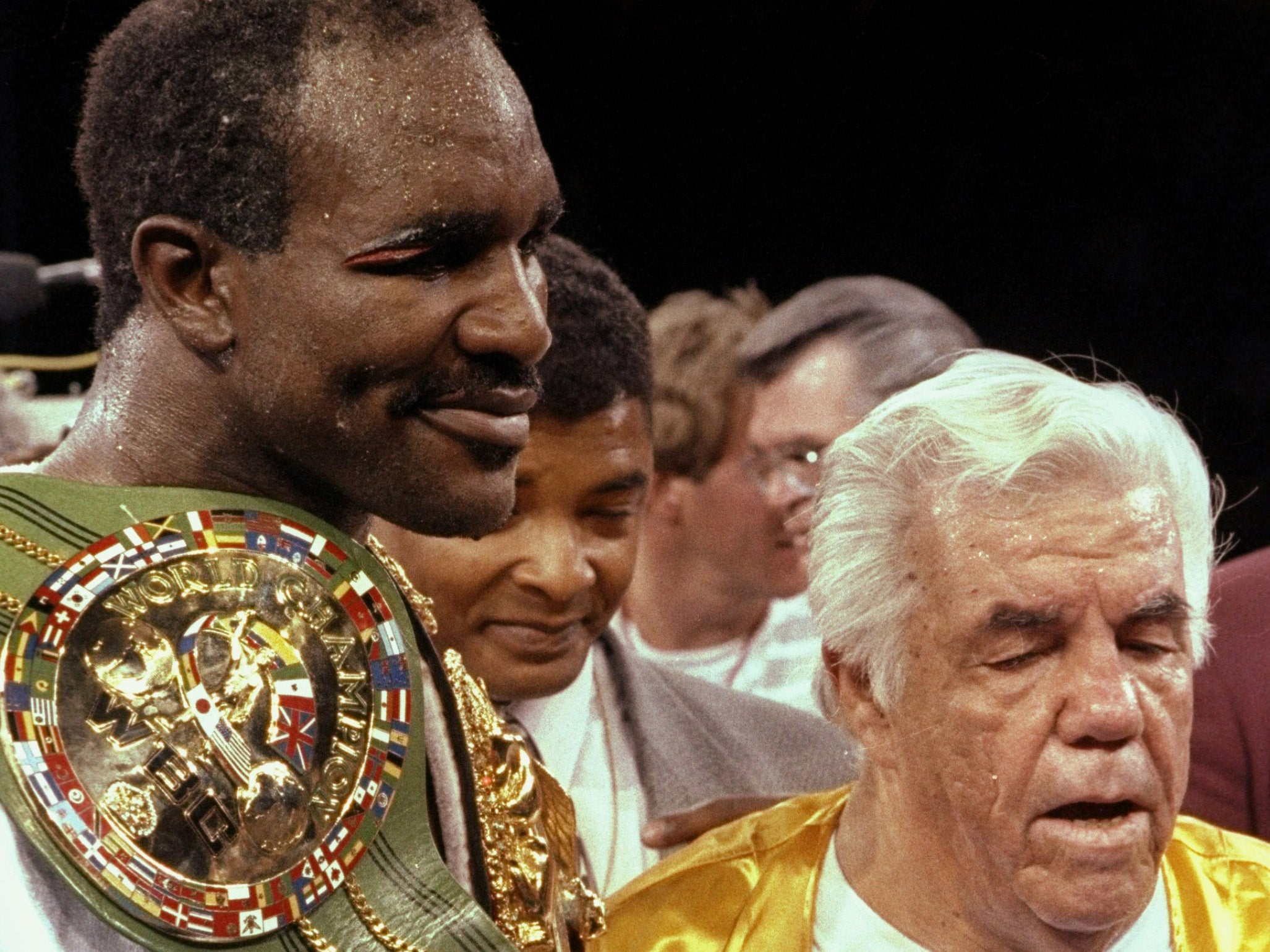

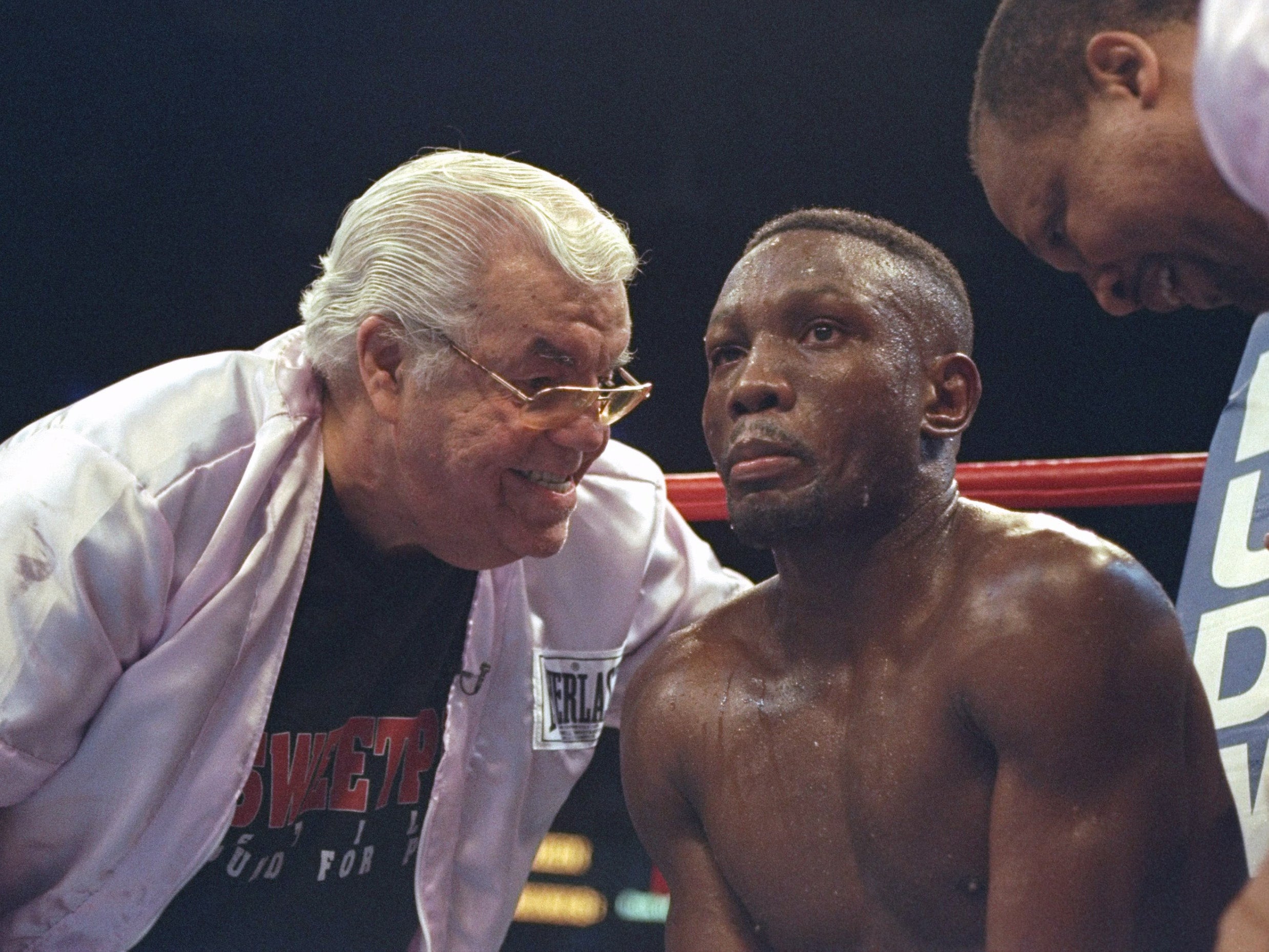

In conversation Duva went on a moveable feast of fights, fighters and some of the sport's most memorable nights, spilling from one ringside to another with his meaty fists whistling in the air to punctuate his point. He was there for Evander Holyfield's transition to heavyweight, at the very violent core of Tony Ayala Jr's brief career and in the corner with a dozen other world champions in real fights.

"Duva is a licensed squealer," said Mickey Duff in 1987 after Lloyd Honeyghan stopped Duva's Johnny Bumphus in London. "I've never known him to lose a fight without causing a commotion." On that occasion Honeyghan had devised a cunning plan; he walked across the ring and, with Duva stepping out of the corner and still half in the ring, he caught and dropped Bumphus with a free shot as the bell sounded. Honeyghan was reprimanded, but Bumphus never recovered and the fight was over a few seconds later and Duva was back in the ring with Bumphus collapsed in his arms. "That was a diabolical thing to do," screamed Duva. "Johnny had no idea and the punch nearly hit me."

As a promoter Duva paraded local fighters as African Warriors, added bagpipes to any particularly pale kid and carried one fighter to the ring in a coffin. He loved being at the fights, small fights and big fights from Las Vegas to tiny halls and his fighters loved him. "I could not have done it without Lou," said Ayala Jr, who was infamous for scrapping once his fights were over. "Lou was always by my side." Duva considered Ayala Jr his grand work, his finest fighter. "Forget (Sugar Ray) Leonard, (Marvin) Hagler and (Tommy) Hearns - forget them all, they couldn't live with Tony." However, Ayala Jr went to prison for rape when he was unbeaten in 22 and just 19. "He was not a bad kid," Duva said. "Just crazy." There was a return to the ring nearly 20 years later for Ayala Jr and then a suicide in 2015.

Duva was the image of a gym dweller from a Forties gangster film, the guy called Mickey with a filthy towel round his neck and an impressive list of casual profanities on his lips. On televised fights in the ‘80s and ‘90s he was asked to stop swearing in the corner; he obliged by cussing in Italian. He never said a word he didn't mean, he was loyal to his fighters and, Duff was right, he caused a commotion every time one of his boxers lost. One night in Las Vegas after Holyfield had come through another savage fight, Duva, shaking his head in admiration, relief and respect, uttered one of his glorious one-liners: "You can sum up this sport in two words: You never know." That line was straight from Stillman's floor 50 years earlier, the same lost institution that made Lou Duva such an irreplaceable man in an ancient business.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments