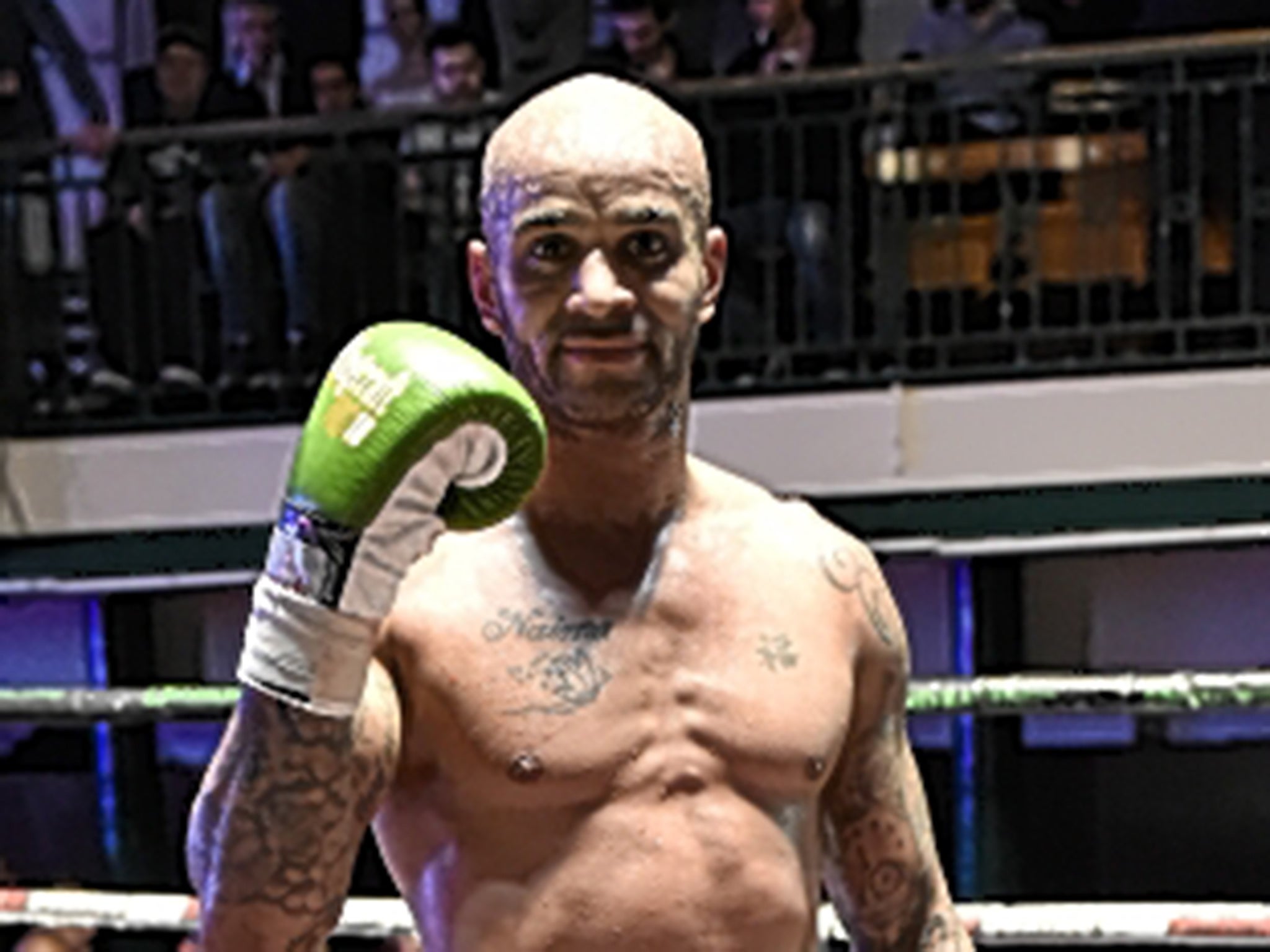

Leon McKenzie: Former footballer's journey back from the brink through boxing

With his football career broken by injury, Leon McKenzie attempted suicide in 2009 only for his dad, Clinton, to save him. They tell Kevin Garside how the son has rebuilt his life with the love of his family to become a professional boxer

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.With due respect to Ben Stokes, Leon McKenzie might just be the most inspirational figure in British sport and, as a suicide survivor, a beacon for the vulnerable who, for whatever reason, struggle to get through the day.

This remarkable ex-footballer-turned-boxer contests his ninth professional bout at the Copper Box Arena at the end of the month, an eliminator for the English super middleweight title against Kelvin Young. McKenzie is 37. He is not doing this to conquer the world, rather to rebuild his own.

McKenzie had it all and lost it all, or at least that is how he internalised his final days in boots when the body was failing and the mind was unable to process or accept the inevitable. There are as many as 18 suicides a day in the UK and, according to the latest figures, at least 10 times that number fail in the attempt.

In 2009, with his career winding down at Charlton, his personal life a mess, McKenzie added his name to that statistic, washing down a concoction of pills with a bottle of Jack Daniel’s in a hotel room in Bexleyheath. Only the rapid intervention of his father, ex-boxer Clinton McKenzie, who raced through the south London traffic from his gym in Dulwich, rescued him from the grim end he sought.

LEON MCKENZIE AND CLINTON MCKENZIE STATS

LEON MCKENZIE:

Super Middleweight

8 fights – 7 wins (3 KO’s), 1 draw

Yet to fight on foreign soil – 7 fights have been in York Hall, Bethnal Green.

Southpaw stance

Debut at 35

Nephew of Duke McKenzie

Duke won both of his fights at York Hall. (McKenzie family undefeated at York Hall)

Won International Masters belt in 7th fight against Croatian Ivan Stupalo

CLINTON MCKENZIE:

Super Lightweight

50 fights – 36 wins (12 KO’s), 14 losses (4 KO’s)

10 fights were abroad – 2 in Belgium, 3 in Denmark, 2 in USA, 2 in Italy and one in Nigeria

Orthodox stance

Debut at 21

Brother of Duke McKenzie

Represented Great Britain in 1976 Montreal Olympic Games – won first two fights before losing to eventual champion Sugar Ray Leonard

First professional fight was in York Hall, Bethnal Green. (Leon has fought there 7 out of 8 fights)

Winner of British Light Welterweight Title in 1978 when he beat Jim Montague in Belfast.

Won both fights that he had at York Hall, Bethnal Green

“A lot of personal things were going on in my life,” says McKenzie when we meet at Trinity House, near the Tower of London. “I was going through a divorce and felt I had lost my identity towards the back-end of my career. Having 18 years in professional football I was never really prepared to finish. I kept getting injury after injury and psychologically it was draining me. I couldn’t come to terms with it. My heart was saying I had one more game in me but deep down I knew it was over.

“I didn’t understand that everything comes to an end, and combine that with all the personal issues I was having, it became a problem. I was isolating myself quite a lot, I just shut off. I didn’t really speak. I wouldn’t wish that on anyone. You don’t realise the strain you are putting on others. It’s a lack of understanding.”

Anyone touched by suicide will know the torment inflicted upon the victims’ families. Bereft of answers, denied understanding, loved ones are sucked into a wretched, endless distress from which there is no escape. McKenzie Senior becomes the hero of this story in more ways than one. Alerted by a call from his partner to the danger his son was in, Clinton pointed his car in the direction of Bexleyheath, arriving at his son’s bedside without quite knowing how he got there.

“I was at work, one Saturday morning. Leon phoned. He was crying,” says Clinton. “I got there in the nick of time. It was like a movie, things happening so fast. I was panicking in the traffic, trying to get around cars. It was touch and go. It was a heartbreaking moment for me. He was unconscious. I was trying to wake him up. I was out of my head with worry. He came around at the hospital in the evening. We were all in a waiting room. We started to talk to him but he didn’t know where he was.”

You can see how such a scene might be euphoric, a deeply loved son and father returned to a family fraught with despair. That is how, in their helplessness, those who have lost imagine a reunion to be. After all, there are more than 6,000 families each year in the UK for whom there are no answers to the question why, no way back for the victim or for them.

But this is not how Clinton felt. Emotional, yes, relieved, certainly, yet all of this layered with confusion and fear that this might not be over. Leon lost a sister, Tracey, to suicide at 23, another who did not know how to respond when the internal walls of her world collapsed. He received the dreadful news via a call from his tearful mother just as he arrived for training at Peterborough. So Clinton maintains a kind of distant watch, alert to the subtle signs that might hint at a downturn in mood.

“Leon has had a massive journey. He has had to pick himself up from then to where he is now. You sense when something isn’t right. He’s my son. You see it in his eyes. It hurt to see him suffering but you don’t think it will lead to suicide. You just don’t know what it is that makes people cross that line. It’s not understood, but people have to talk about it, explore their feelings, as hard as it is.

“We got him back. I just want to hold him all the time. I see what he is doing, his passion for boxing. He has his bad moments but we have a little chat, you know, a phone call and he is back again. You can never say never but I hope to God he never goes back to that point. He sees his beautiful kids and he is working towards building a future for them.

“I don’t know what makes people want to do that. Maybe it is just not knowable. But that kind of depression is in people. All we can do is show love and understanding. And that’s what I do with Leon every day. I’m proud of him. He has a lot to give. A lot of people can look at him and say, ‘You know what, I’m down but I can get up’.”

And that is the real message in Leon’s Indian summer as a boxer. He doesn’t need a title to validate his career. Each time he steps outside his front door into the big, wide world he records a victory, affirming his desire to battle on while simultaneously demonstrating to others what can be done with the right support.

“I want to inspire people,” he says. “I’m fighting for so many people. People that struggle, people that are not doing too well. There is a bigger picture. If I were to sit here and be totally honest I would admit to still having bad days. I would be lying if I said I was totally healed but I’m learning how to cope, that’s the key. I try, day in, day out. I fight in and out of the ring.”

In this, Leon is rekindling the spirit that Steve Coppell recognised when he gave a callow 15-year-old from Thornton Heath a shot at the big time 22 years ago. “I had to work. When I signed for Crystal Palace I was coming from Sunday League. I was very raw and so far behind all these brilliant kids. I thought I was good but I wasn’t. They had the spacial awareness and technique that I had never been taught.

“But Steve Coppell saw something in me, the same things he saw in Ian Wright. He didn’t say I was as good but he saw something and every day he had me practising, first touch, heading etc, all after training. Two years later, aged 17, I made my debut and kicked on from there.”

A loan spell at Peterborough, where he scored eight goals in 14 games, led to a permanent move in 2000. At the age of 22 he was on his way. The goals-to-games ratio continued at the same pace, earning a move to Norwich three years later and, ultimately, a season in the Premier League, tasting the elixir of goals against Manchester United and Chelsea. “You have such highs. I can’t explain what it’s like playing and scoring in front of 40,000, 50,000 people. Me, just a kid from Thornton Heath.

“I watch football now and I think, ‘Wow, I used to do that, and did it well’. I played football for 18 years. There were better players than me but ask people who they would want in their team and they would say Leon McKenzie because of the way I played, the passion I had for the game. I was exciting. It’s the same with boxing now. That’s why I have ‘The Secret’ inscribed on my shorts. It’s a secret I hold inside, that given the chance I always knew I had what it takes. The only thing we don’t have is time. But I don’t have anything to prove. Every time I step in the ring I’m a winner.”

McKenzie is trained by his father, a man who fought the great Sugar Ray Leonard at the Montreal Olympics and held the British and European light-welterweight crowns. The love and respect they have for each other is deep and growing. And their shared experience of that desperate day in 2009 informs them still in a way that gives hope to the vulnerable.

“It was part of my journey, part of my life. They told me I was one or two pills from not waking up, so thank God. I see life in a different way now and I am so much more prepared. Once I came through the attempted suicide I started to fight. I really did. Some days weren’t great. You just try to get hold of yourself and kick on. The interesting thing with my story is that two years ago I was in a worse position than I was in 2009. I had gone through my second divorce, was missing my children. I had to move back into my baby sister’s house. Imagine that, at 35.

“I had to get on a bus every day from Woolwich Arsenal to Crystal Palace to train, just to keep my mind active. Most people would have broken. I remember many times going back to my sister’s house and crying. You have to understand the emotional psychology of going from having so much to nothing. That showed a lot about me. I held on. I hadn’t made my debut in boxing then. We were still unsure about that. So to be sitting here now, I feel a little bit special, to be honest.

“My dad calls me up every day. My kids love me. Some days it’s a struggle to get up, never mind go training, but those calls, those glimpses of my kids help me to fight. It’s not easy. Some days the depression creeps in. When I’m in that dark place people will know I’m not myself. My dad asked me the straight question, ‘Are you suicidal?’. Asking that is a big deal.

“But until you understand depression, you can’t ask the question. If you are having those thoughts, it has to be addressed – and by asking the question you are doing that and can get the necessary help.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments