John Conteh’s neglected brilliance must be fondly remembered beyond the shadow of Atlantic City

The Liverpudlian was cruelly denied against Matthew Saad Muhammad in 1979 but, as Steve Bunce argues, should not have been near the ring in the rematch

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It was the end for John Conteh long before the first bell of his last world title fight in Atlantic City back in 1980.

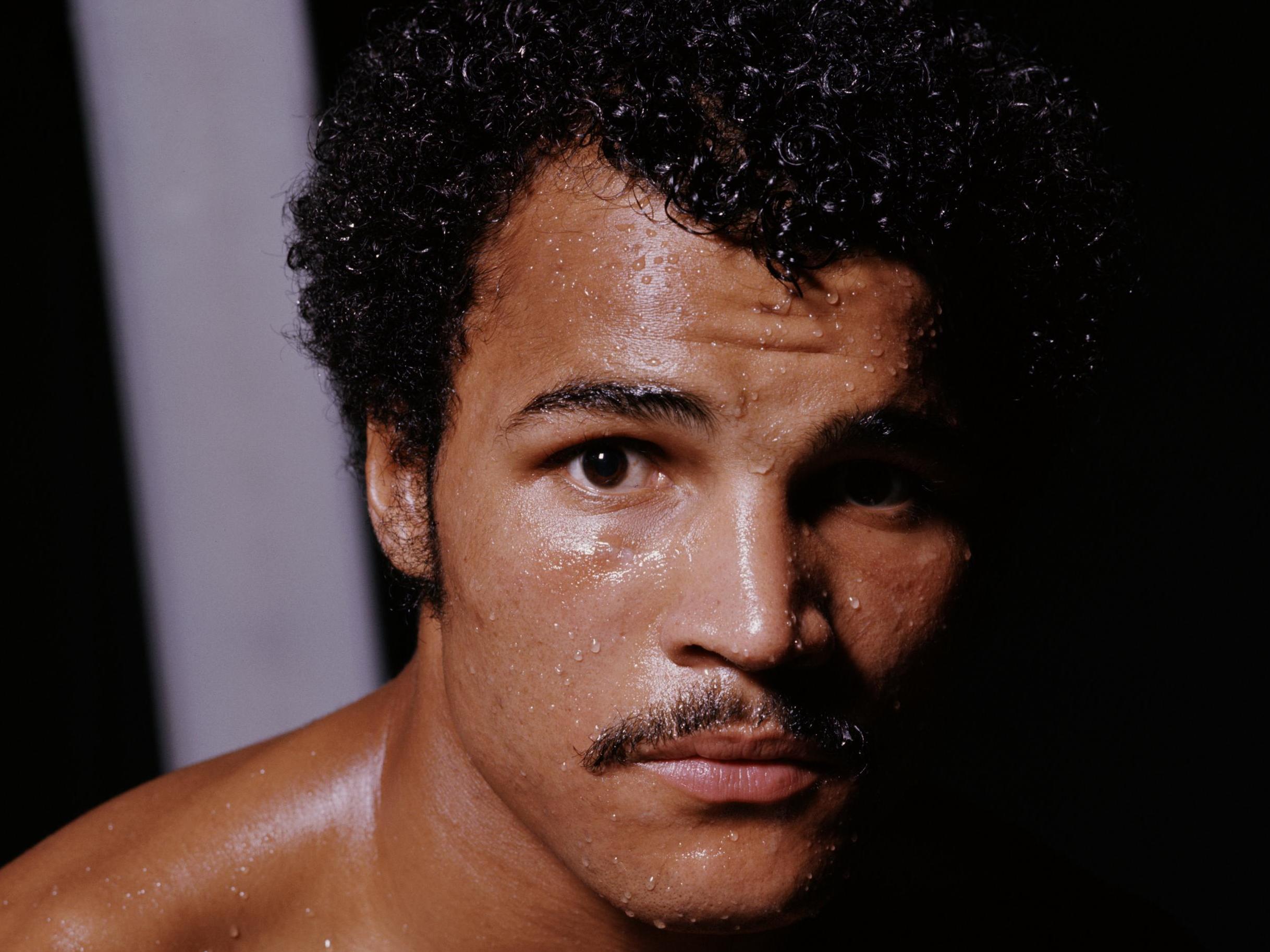

Conteh had been a world champion in 1974, he had been the sport’s sweetheart, a man held tightly in the arms of Playboy bunnies for publicity pictures and the man Muhammad Ali called “too pretty.”

On that that late, late March night the demons visited Conteh as he walked to the ring for his world title rematch with Matthew Saad Muhammad. The dark boxing spirits fluttered so easily on his shoulders, and in his head, that it was clear he should have been under examination and not under the bright lights.

The pair had met in the same ring the previous summer; it had been a bloody classic, brutal, nasty and controversial fight. The rival corner men had traded punches between rounds and Conteh had lost the narrowest of decisions. It was unforgettable, a reminder of Conteh’s neglected brilliance. At the time the booze and binges had started to disrupt Conteh’s commitment to training and the essential sacrifices that boxing requires. He was living a double life, make no mistake, and by the time of the rematch his life was in turmoil.

In the first fight there was the cruellest of outcomes for the sweetest of men. Conteh should have won on a cut-eye stoppage after a gash opened above Muhammad’s eye in round five. However, in the American’s corner a veteran cutsman called Adolph Ritacco applied his secret coagulant to the wound; by round nine the bleeding had stopped and a black rind was visible concealing and containing the cut. At the end of round nine, George Francis, Conteh’s loyal and loving cornerman, went to interrupt Ritacco’s work, demanding to know what was being used to closed the cut; punches and words were exchanged and the pair were separated.

“It was a joke, I was fuming,” said Francis. He was right, by the way.

“It’s my formula, I told the doctor, but I was not telling that f***ing limey,” replied Ritacco.

In round 14, with the fight gently poised, Conteh was dropped twice; the knockdowns cost him the title; had he stayed on his feet he would have won the fight. It is that simple, that cold.

In 1980 they met again in the very last days of March.

People can lie all they want and reinvent boxing history to serve any narrative, which they do on a regular basis, but it is clear that John Conteh should not have been anywhere near the Atlantic City ring that night for the rematch with Muhammad. Conteh knew it long before he stepped from his dressing room and walked to the ring.

“I never wanted to be there, I kept asking myself what I was doing there,” Conteh said. He was, however, making $366,795 for offering himself as a sacrifice. It was unpleasant from the start, Conteh was just not involved, not connected.

In round four, Muhammad dropped Conteh five times with shots to the ear, head and gloves. It made no difference, Conteh was not really in the ring and, in truth, any type of punch would have dropped him; a light breeze from the exit could have brought him trembling to his knees. It was stopped with just 33 seconds left of the fourth and an indignant Reg Gutteridge jumped on Conteh. Rather disturbingly, Gutteridge, an icon in the broadcasting game, had doubted the power of Muhammad’s punches and wondered how they had causes so much damage?

The implication was that Conteh could have done more. Conteh was subdued, unclear, and dreamy in the interview – Gutteridge got his answer in Conteh’s distant eyes and dead voice.

“I never wanted to be on the floor in that fight,” Conteh told me. “I kept thinking I should be out drinking champagne – that’s what I was thinking when I was on the floor.”

During the fight the voices were talking to John; there was a debate going on his head. He was not fit to fight. When it was over he went on a one-day bender and was eventually restrained as he ran naked down the hotel corridor. He was tackled by George Francis, the pair in tears as they grappled.

Francis was able to get Conteh to a bed, strap him down and sit lonely, painful vigil by his side for a night as the boxer fell into a deep and disturbing sleep. That was the end he should have been spared.

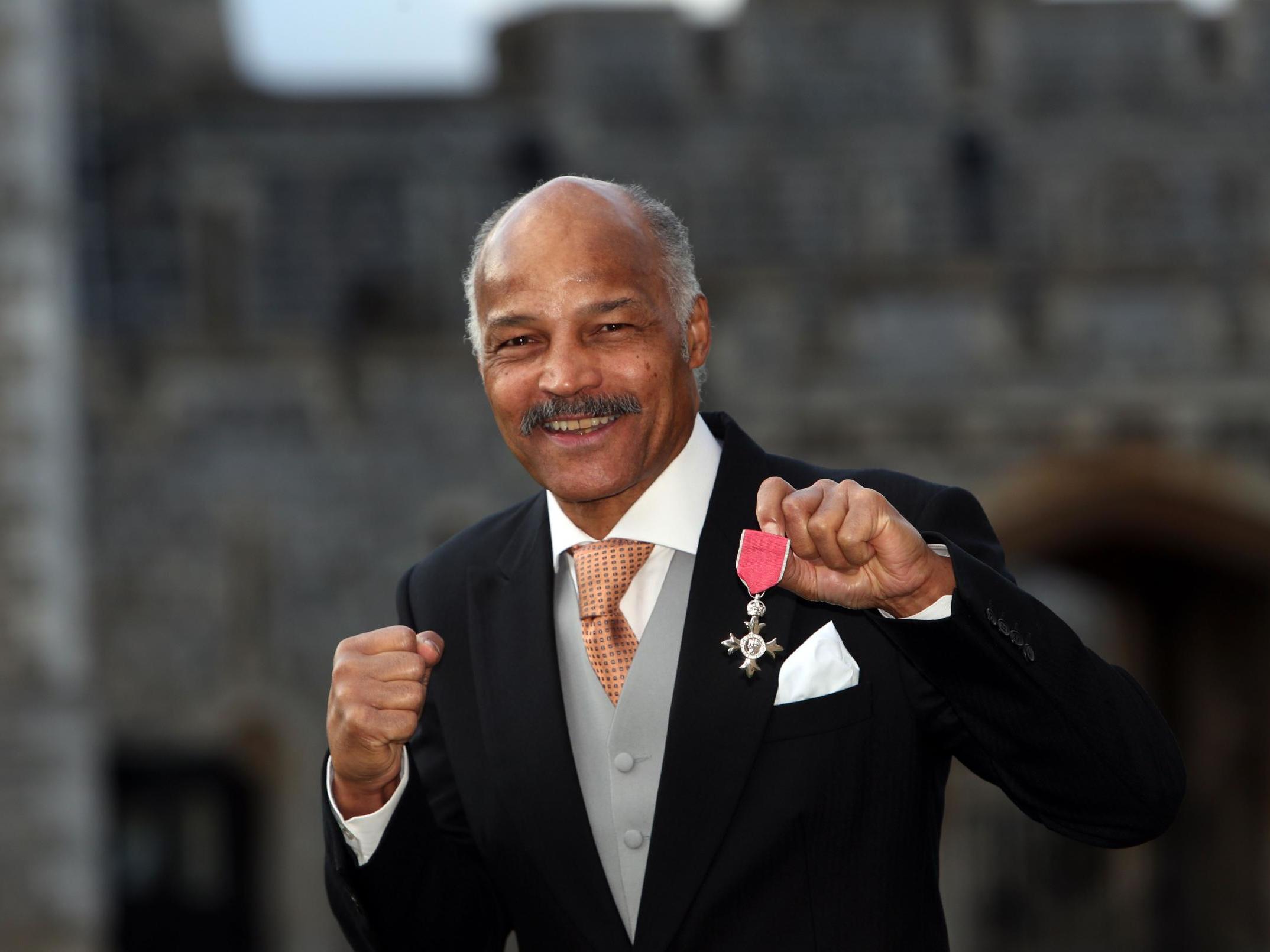

It was not John Conteh in the ring that final night, just a shadow of a man, muttering, going through the motions and taking a beating. The real John Conteh did emerge several years later, clean and sober and hopeful each day, and he, like the real fighter, is a great man.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments